Vladimir Putin finds himself caught in a variety of paradoxes none more glaring than his simultaneous need to defend the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact by which the USSR became an ally of Nazi Germany and his need to celebrate the Great Victory over the Third Reich, according to Yevgeny Ikhlov.

On the on the one hand, the Moscow commentator says, Putin needs the Great Victory because it completes the shift from a focus on communism as the explanation for the Soviet Union’s win to one on Stalin and his totalitarian system as the source of that triumph.

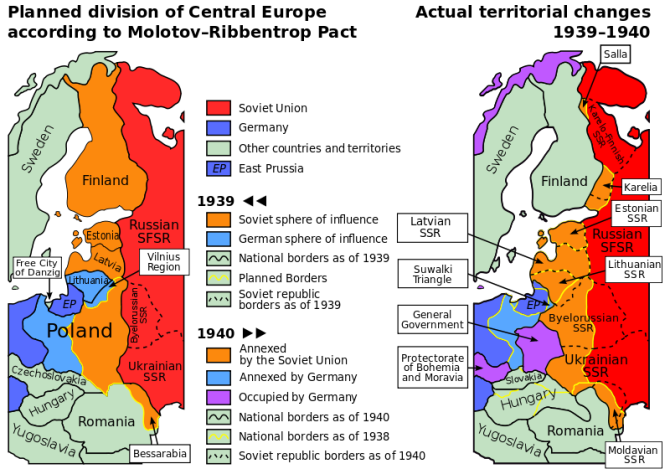

And on the other “and at the same time,” the Kremlin leader is prepared to defend with “all the authority of the Russian state” Stalin’s alliance with Hitler which is “delicately called ‘the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact’” because “that pact for the first time legalized zones of Soviet influence” beyond the borders of the USSR and based on “continuity” with the Russian Empire.

This is just one of the insights contained in Ikhlov’s article about the importance of mythologizing the past in a country like Putin’s Russia, one where “the weaker the institutions in the state are, the stronger must be the all-embracing mythology.” Indeed, his system is based on the idea that “the picture propaganda provides of the world is the only reality for the population.”

Up to a point, this approach has served Putin well. It has “rooted Putinism in Russian political history.” But the problems begin when one tries to make that political history consistent, something that is virtually impossible without blatant falsification because various events point in so many contradictory and incompatible directions.

And that in turn means, Ikhlov says, that “the more improvisations are introduced into this renewed cult, the stricter will be the struggle to ‘defend history from distortions and falsifications’ … There are many countries which have introduced punishments for denial of crimes against humanity… but there are only a few which [like Russia today] are criminalizing the unmasking of historic crimes.”

The approaching celebration of Victory Day, of Russia’s attempt to take credit for the defeat of Nazism, highlights this “real schizophrenia” in Moscow’s position: “One should not call oneself the main victor over Hitlerism while being proud of the alliance with this same Hitlerism” at the start of Hitler’s war to “seize Europe.”

There is a logic in each of the narratives, Ikhlov argues, but trying to bring them together into a single narrative is “impossible,” because “to be at one and the same time an anti-fascist, an anti-communist, and an anti-liberal in the contemporary understanding of the ideological spectrum cannot be done.”

The only way it can be done, he suggests, is with “one’s own fascism,” or as Putin would put it “’the Russian world.’”

But there is a deeper paradox and problem for Putin, Ikhlov says. It consists of the fact that Russian history consists of a series of “hermetically sealed periods,” each of which engages in the denial of its predecessor, as the late philosopher Aleksandr Akhizer pointed out a generation ago.

That makes stability very difficult as does “the struggle of two competing directions” in each, “each of which offers mutually exclusively approaches to the overcoming of internal crises.” Typically, the leaders of a country must make a choice; Putin has been trying so far to avoid doing so.

“Putinism’s difficulties began when it ceased to be simply ‘velvet Pinochetism,’ a regime of authoritarian modernization and began to convert itself into ‘an oprichnina,’ into market Stalinism,” Ikhlov says. That violated a chief requirement of myths: a certain consistency in their internal logic.

According to the Moscow commentator, “isolationism and anti-Westernism require support in a messianic legend. But Orthodox fundamentalism remains too much an exotic phenomenon.” Moreover, it is dangerous because it contains within itself “a very strong anti-state attitude.”

Moreover, “all the misfortune of Putinism” is that doctrines like “Moscow is the Third Rome” have the effect of “denying development and transforming life into an uninterrupted waiting for the end of the world.”

That leaves Putin and Putinism with few options, Ikhlov argues. Indeed, the only one really available is the implementation of a 160-year-old tradition that was “aborted by Bolshevism – the development of right-wing fascism.”

During that period, he says, Russia has moved “along a totalitarian arc: from radical-left form in the shape of Bolshevism with a gradual falling away from utopian pseudo-Marxist ideas to the side of right-wing totalitarianism which recognizes and cultivates obscurantism, chauvinism and petty private property.”

This evolution, Ikhlov continues, has included “periods of black hundreds-style post-war Stalinism, the anti-market ‘left fascism’ of stagnation … and up to the current dawn of the Russian conservative revolution, the first conquests of which have already appeared in Crimea and ‘Novorossiya.’”

“The evolution of totalitarianism from communism to fascist was broken off only three times – during the five years of the New Economic Policy, the decade of the Thaw, and the ingloriously just concluded liberal Perestroika thirty year period.” It is now resuming with full force and with all its contradictions in play.