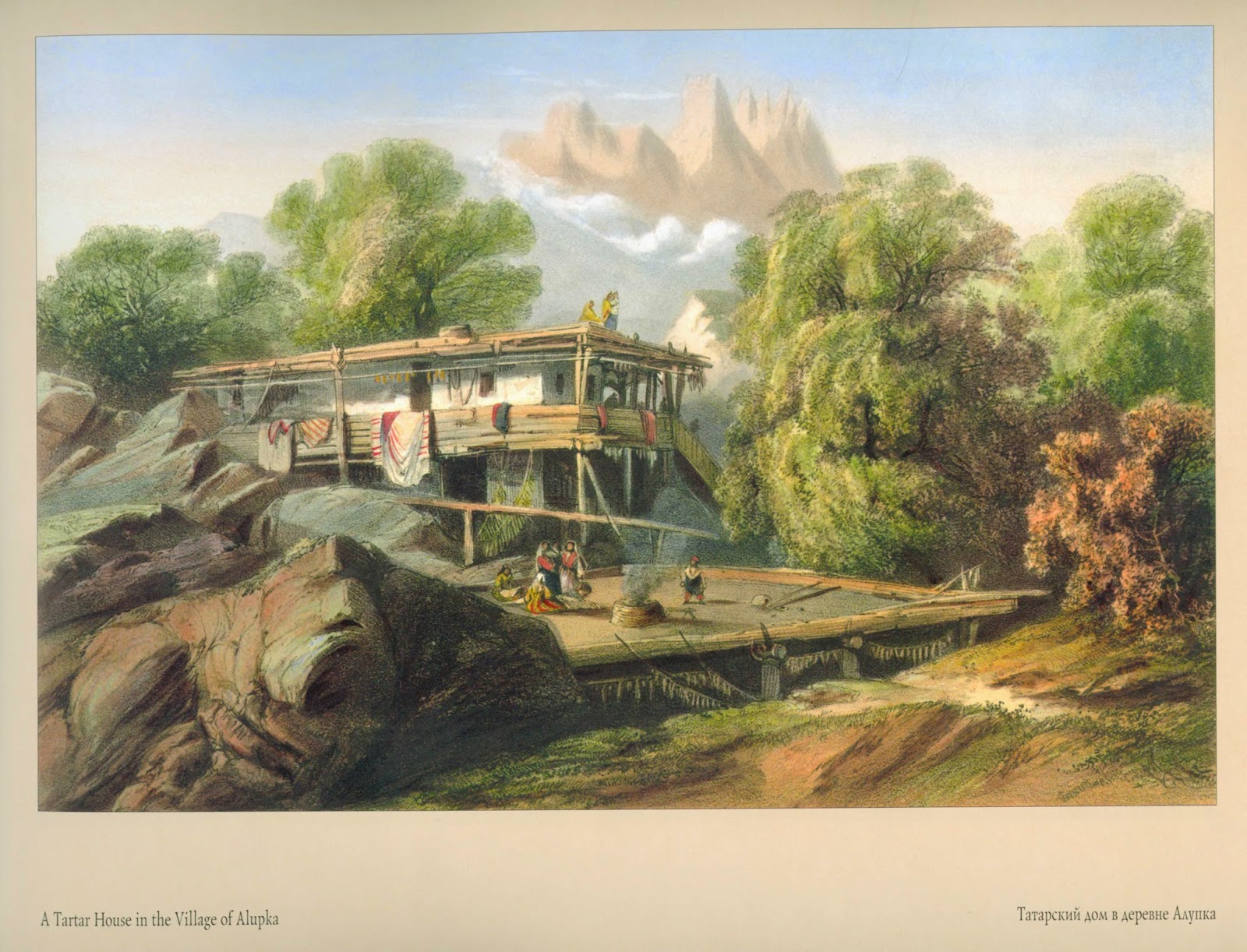

Until recently, little was known about the Crimean Tatars or their historic homeland, Crimea. These turkic people’s history goes back to the 12th century. Their modern history, under Soviet rule, is one of deportation, exile and loss. "Son of Crimea: Struggle of a People" was directed by Neşe Sarısoy Karatay, known for her award-winning documentaries, and produced by Zafer Karatay, who also wrote the script for the Turkish version. A veteran producer at the TRT, Mr. Karatay is known for his documentaries on Crimean Tatar history and culture. The film is an important historical account, incorporating interviews with hundreds of eyewitnesses and survivors, politicians and experts, documents from the archives of the former USSR, as well as thousands of photographs from private and public collections.

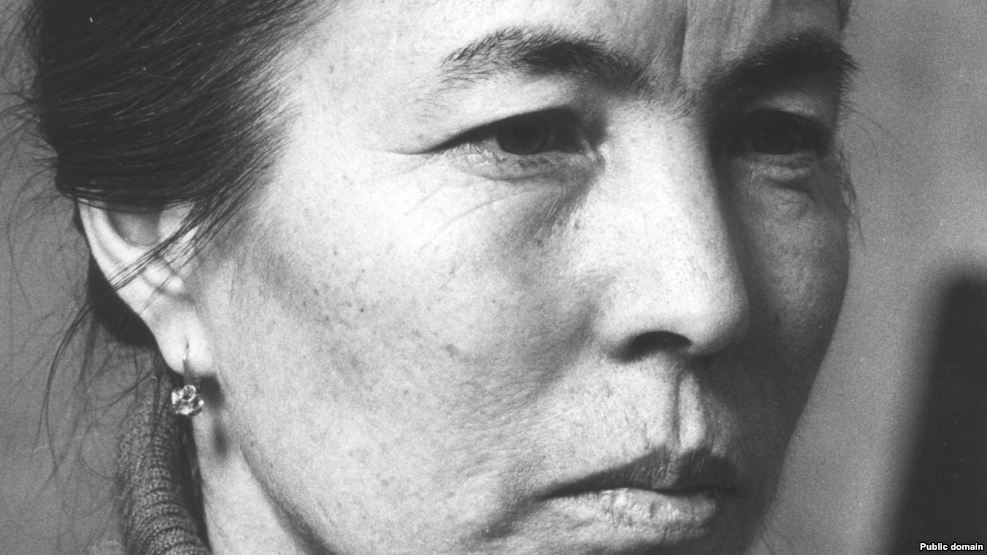

This documentary tells the story of Crimean Tatars' long, arduous and peaceful struggle to return to their homeland. Accused of cooperation with the occupying Nazi forces during World War II, the Soviet authorities exiled the Crimean Tatars to Central Asia and the Ural Mountains in 1944. Mustafa Dzhemilev (also known as Mustafa Kirimoglu or Jemilev), well-known in human rights community but little known in the West, devoted his life to his people’s struggle for justice and repatriation. A Nobel Peace Prize nominee, Dzhemilev is one of the most important human rights activists in the former Soviet Union, having served six prison terms, over 15 years in the Soviet GULAG, and survived the longest hunger strike in the history of human rights activism.

The film divides the story of the modern Crimean Tatars into 9 chapters, beginning with the Soviet deportations. Nearly half of the women, children and men forcibly relocated died in the first two years, many in transit, others unable to survive the inhumane conditions. Commentators explain the deportations were in fact prompted not by any purported Nazi collaboration but as a pretext to eliminate from the Soviet Union the Tatar Muslim populations from the areas bordering Türkiye. The first and second chapters are available to view on youtube:

Part I. Deportation

On May 18, 1944, the entire Crimean Tatar population in Crimea, mostly women and children, was subjected to forced relocation, while the men fought in the Soviet Army or with Soviet partisans. The Jemilev family, with baby Mustafa, survived the 22 day-journey and ended up in Uzbekistan. Interviews with survivors of the deportation reveal mistreatment of the deportees by Soviet soldiers, unsanitary conditions in the cattle wagons used to transport the people, and inhumane handling of bodies of those who died during the long journey.

Part II. Survival

Nearly half of the deported Crimean Tatars died during transit or in places of exile within two years. Eye-witness accounts detail the horrible conditions that the deportees found themselves in--scarcity of food, lack of potable water and substandard shelters. People died of hunger, disease and exposure to cold and harsh environment, and lost many family members. Commentators explain the true reasons for deporting the entire population of Crimean Tatars: eliminating the Tatar element from Crimea and removing Muslim populations from the areas bordering with Türkiye.

Part III. Rebirth from the Ashes

Crimean Tatars were forced to live in Special Settlement Camps, where their movement and rights were restricted. After the death of Stalin in 1953, eventually ethnic groups deported from the Caucasus were allowed to return but not Crimean Tatars. The authorities released the Tatar population from the Special Settlement Camps in 1956 and relaxed the rules somewhat. Crimean Tatar activists launched a campaign to gain their rights and clear the charge of treason leveled against their people. A series of petition drives gathered thousands of signatures and marked the beginning of the Crimean Tatar National Movement. If Stalin and his associates had dreamed of ethnic cleansing of Tatars from Crimea, they would be proven wrong.

Part IV. A Nation That Flourished in Exile

Crimean Tatar activists went door to door to explain the national movement that aimed at the rehabilitation and repatriation of their fellow Tatars and continued to collect thousands of signatures. The first political trial of Crimean Tatars took place in Tashkent in 1961. They established a permanent lobby in Moscow in 1964 and sought contacts with Soviet human rights activists there. A delegation Crimean Tatars delivered a 33-page petition with over 130,000 signatures to the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1966. The same year, Mustafa Jemilev was sentenced to 18 months in a work camp for refusal to serve in the Soviet Army.

In 1956 the Crimean Tatars, having finally been released from the Settlement Camps, launched a grassroots campaign to gain their rights through a series of unprecedented petition drives. This marked the beginning of the Crimean Tatar National Movement. In the 1960s, they established a permanent lobby in Moscow and made contacts with Soviet human rights activists. Crimean Tatars also supported the larger Warsaw Pact dissident movement, courageously joining anti-government demonstrations in Uzbekistan, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere.

After years of petitions, demonstrations and political trials, the Soviet government lifted the wartime charges of treason in 1967. But Dzhemilev wasn’t freed for another 20 years. Around the same time, the Crimean Tatars began returning to their homeland in Crimea in the late 1980s, only to find Russians and Ukrainians living in their homes. Despite prejudice and harassment, the Crimean Tatars have remained peaceful, following the non-violent principles adopted by Mustafa Dzhemilev.

The official Web site of "Son of Crimea" is in Turkish and includes many photographs from the documentary: http://www.kirimoglu.org/

English summary of "Son of Crimea" was written by Inci Bowman, International Committee for Crimea, Inc., Washington, DC. Summary of all episodes here: http://www.iccrimea.org/reports/son-of-crimea.html