Andrey Parubiy, the speaker of the Verkhovna Rada, is among those who say that Ukraine today should be seen not as a newly independent state, which arose as a result of a declaration in August 1991, but as a continuation of the Ukrainian Republic of 1918-1920 that was suppressed and occupied by the Soviets.

As a result, he says, August 24th should be marked not as the Day of Independence but rather the Day of the Restoration of Independence

and that this should be fixed by law.

That may seem a matter of hairsplitting to many, but in fact, it not only has enormous consequences – including the implication that between 1920 and 1991, Ukraine lived under Muscovite occupation – but is part of a general trend among many post-Soviet states to recover their pre-Soviet history and stress continuity with it as the Soviet period recedes into the past.

It has long been generally accepted that since 1991, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have had an easier path than the former Soviet republics in large measure because they, unlike all the others, stressed their continuity with the pre-war republics, insisted on legal continuity and occupation, and have thus been engaged in restoring rather than creating something entirely new.

Over the first two post-Soviet decades, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia have devoted varying amounts of official attention to and celebration of the anniversaries of their pre-Soviet statehood, most prominently in 2008 on the 90th anniversary and with plans for the centenary in 2018.

The efforts of the three Transcaucasus countries to insist that they have a pre-Soviet past they can look to and build on does not in the nature of things put them in the same position as the three Baltic countries – their earlier experience was both far shorter and far more troubled – but it does set them apart from the other post-Soviet states.

Parubiy’s statement suggests that at least some in Ukraine would like to see their country also stress its continuity with the previous period of Ukrainian independence. In doing so, such people clearly hope to stress that

But there may be more immediate reasons behind this move as well. On the one hand, an emphasis on state continuity more than implicitly suggests that what occurred between 1920 and 1991 was a Russian occupation. And on the other, that in turn implies as the Baltic countries have insisted and the world agrees that

Both these things can mobilize Ukrainians whose country is now being invaded and subverted by the Russian Federation:

- by promoting a deeper sense of patriotism among them and

- by giving them a sense that their state is no recent arrival but something with a real political history that they can look to and be proud of.

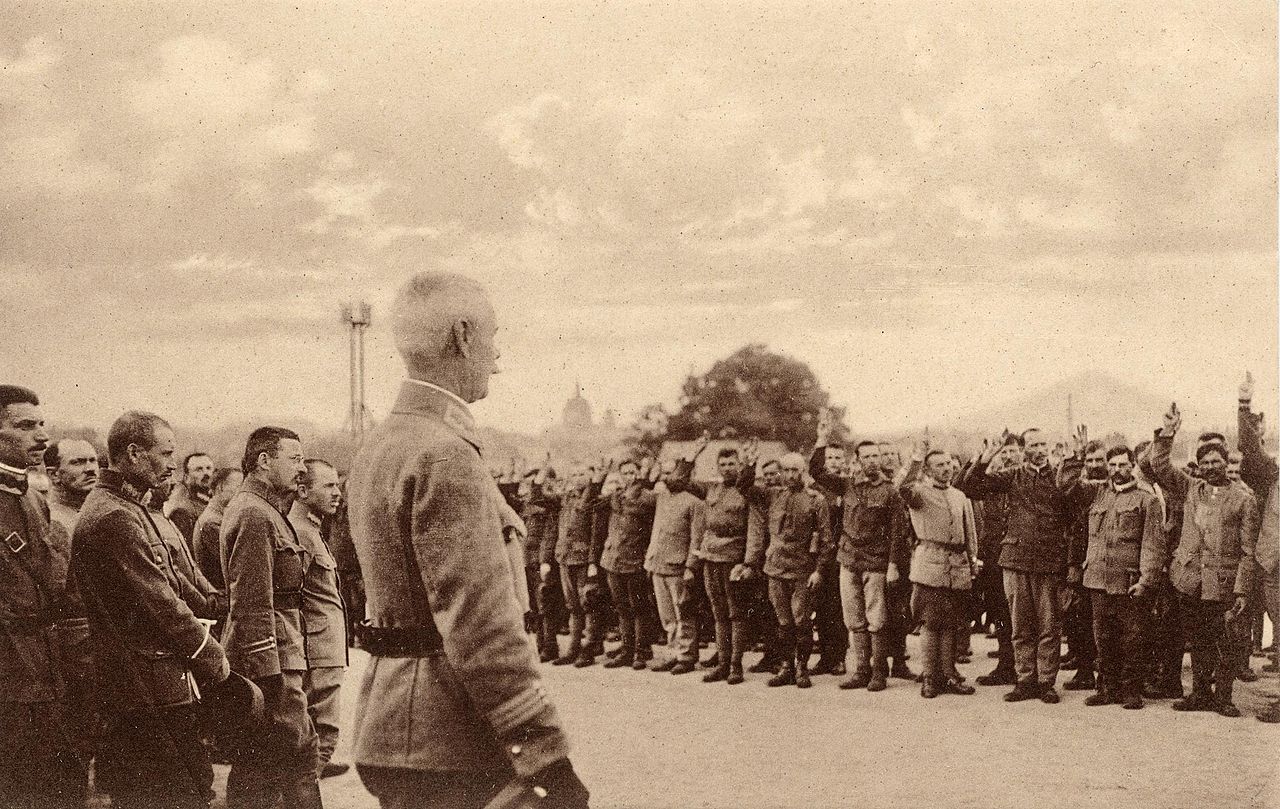

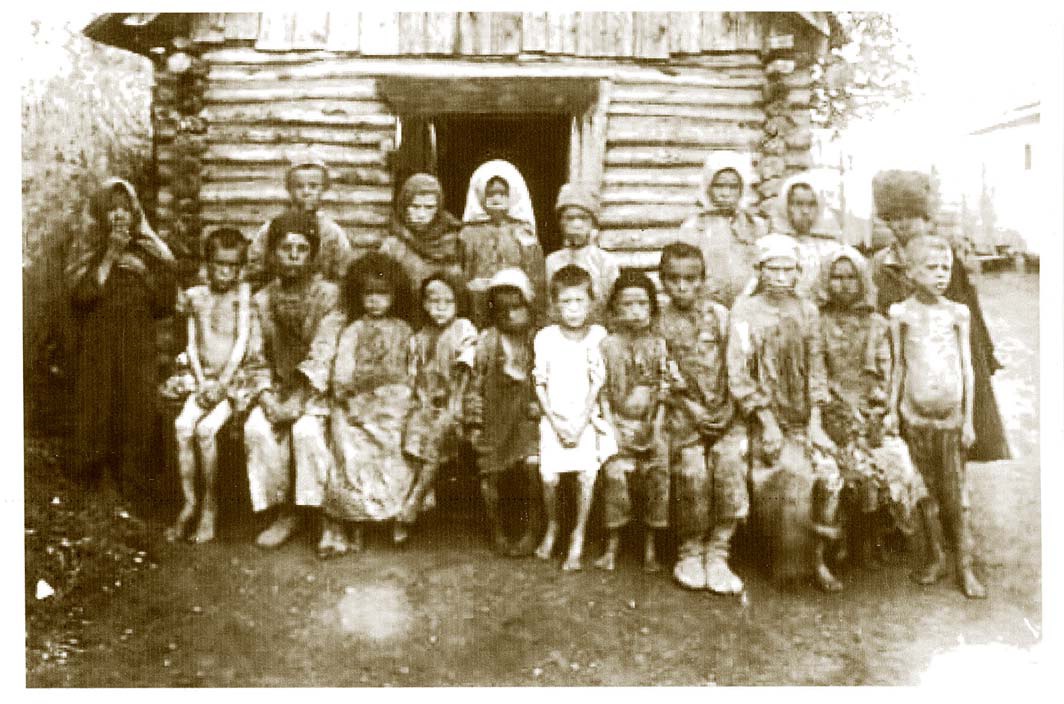

Unfortunately, there is another consequence of such stress on continuity. The period between 1917 and 1920 in Ukraine was a profoundly troubled one, and there are pages in it that no Ukrainian or anyone else can be especially proud. Russian propagandists are certain to pick up on that if Kyiv does decide to emphasize its continuity with the earlier Ukrainian state.

Related:

- Ukrainian independence exposed bankruptcy of all three Russian imperial projects, Ikhlov says

- Ukraine: 25 moments of independence

- How Russians see Ukraine's independence