Two images of Stalin’s Great Terror have long competed in the West and even in some former communist countries. The first, offered by Arthur Koestler in his novel “Darkness at Noon,” views what happened as rationalistic with a minus sign, the product of a single intelligence, and focused on the elites.

The second, offered by Victor Serge in his novel “The Case of Comrade Tulayev,” suggests that what happened was far less rational, was put in motion by one man (Stalin) but then rapidly metastasized as subordinates competed for preferment, and involved not just a limited number of elite victims but large portions of the population.

Despite all the documentation provided by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Robert Conquest among others, many prefer Koestler’s image to Serge’s, not only because it allows them to reduce the extent of the horror of the Great Terror to something more intellectually manageable that they can then excuse if not justify.

But now as terror is once again spreading through Russia under Vladimir Putin, it is increasingly clear that Serge had the more profound insight into that phenomenon because what is taking place now, while set in train by Putin, is becoming even more horrific as his subordinates compete for preferment and as the number of the victims is increasing.

Although he does not mention either Koestler or Serge, Ukrainian commentator Vitaly Portnikov draws attention to the importance of this distinction in his discussion of the latest persecution of the Library of Ukrainian Literature in Moscow by the Russian authorities.

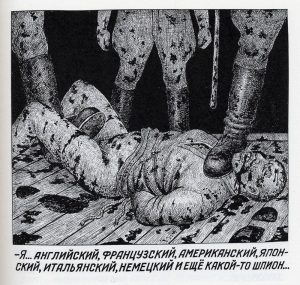

This action, Portnikov suggests, may appear to some be a kind of “diabolic” effort by the Kremlin to demonize all Ukrainians. “But in fact, this is simply a careerist move, the pursuit of higher ranks” and other benefits by lower-ranking Russian officials who, although inspired by their bosses, often are acting in their own “creative” ways.

Moscow’s Library of Ukrainian Literature hardly was a disseminator of radical anti-Russian views, Portnikov says, even though some of the thousands of Ukrainians in the Russian capital donated books to it and were proud that there was at least one institution there bearing the name “Ukrainian.”

But that was too much for the hurrah patriots of Russia, and their latest attack on the library and its head, Natalya Sharina, resembles nothing so much as moves by “some kind of ‘fraternal parties’ in North Korea,” people who imitate political activity and “then for this very same imitation send people to the camps.”

According to Portnikov, Sharina did everything she could to reduce the Ukrainian library to the status of yet another district library; but that wasn’t enough: “Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin] says that Russians and Ukrainians are one people and therefore it is clear to every patriot that there are no Ukrainians.”

But somehow in the center of Moscow there is a library which is “called Ukrainian and which has literature in a funny language. “What if the children should see it?” That reflection was enough for investigators to conclude that “Ukrainian and extremist are practically one and the same thing,” and to ensure they’d find what they needed by taking it with them.

That didn’t take a decision in the Kremlin as those who accept what Koestler wrote might think; instead, such an action happened as earlier actions did in Serge’s novel, with the leader giving a direction and then those below seeking to fulfill and overfulfill the plan by finding ever new targets.

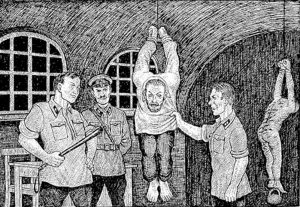

Because that is so, it is impossible to limit the blame to either Putin or Stalin. They may bear primary responsibility, but they are surrounded by what some have described in another context as “willing executioners.” In the absence of a concerted effort, it will thus be far more difficult to overcome this pattern than many assume.