The Holodomor Memorial Museum in Kyiv has opened an exhibition on the artificial resettlement of Russians and Belarusians to eastern Ukraine after the Holodomor (famine/genocide) of 1932-33. The exhibition includes secret party documents that depict this process in detail. Museum workers are convinced that information on the violent assimilation policies of the Soviet Union may partly explain separatism in eastern Ukraine today.

The artificial resettlements and forced assimilation of Russians and Belarusians on Ukrainian lands begin immediately after the Holodomor of 1932-33. The most active segment of the Ukrainian population had been wiped out, but the land needed tending and new residents, explains historian Nina Lapchynska, the head of the museum's research department. In 1939 the All-Union census recorded the changed ethnic population in Ukraine. Much later, the new "locals" in eastern Ukraine would tell Holodomor researchers that "there was no famine." Lapchynska believes this mind-set, as well as separatist attitudes in modern Donbas, are the results of the population resettlements. Russians were brought to the Kharkiv Oblast in Ukraine from the Chernozem Oblast in Russia (which today is divided into the Kursk, Chernozem and Tambov oblasts). There were altogether 329 waves of migrants, representing close to 23,000 families. According to the Central Committee of the Soviet Union, the local government was responsible for welcoming the new arrivals.

"Ukrainian peasants had to clean and whitewash the houses, repair the yards (since the yards of the deceased were dismantled for wood), and remove the corpses," Lapchynska explains. "They were ordered to prepare the housing and the farm implements so that the migrants could begin to work immediately. They (migrants) were also given incentives: exemption from agricultural and meat taxes for two years, etc.," she says.

Russian settlers given grain seized from Ukrainians

According to Lapchynska, not only families but entire collectives were resettled. When a collective farm moved, it had to hand over grain and then upon presentation of a receipt was given the same amount of grain in the new location -- the same amount that had been taken from Ukrainian peasants during the Holodomor.

Conflicts arose between the locals and the settlers since the locals received no benefits. "In one of the documents there is even testimony that the local collective farms had to purchase phonographs for the new settlers," she says. Special Russian-language classes were organized for the Russians, and Russian language newspapers and books were brought in. Additionally, the Ukrainians who had left during the Holodomor and who succeeded in returning discovered that their homes had been occupied and that handing back property to the original owners was prohibited.

This exhibition is a logical continuation of previous projects of the Holodomor Memorial Museum, explains Yana Hrynko, a researcher at the museum.

"We have launched a series of exhibitions called The crimes of Soviet totalitarianism

. This exhibition was preceded by an exhibition dedicated to the liberation struggle in the 1920s. After the first famine in the country there were about 4,000 uprisings. And the response to opposition was genocide. The Holodomor of 1932-33 was a powerful blow to Ukrainian independence. Here were are talking about a violent assimilation policy: to wipe out a part of the Ukrainian population and replace it with people presenting no threatening national concept," Hrynko says.

The exhibition dedicated to the artificial resettlement of Ukrainian lands has been organized with the support of the State Archival Service and the state archives of the Security Service of Ukraine.

Photo Captions

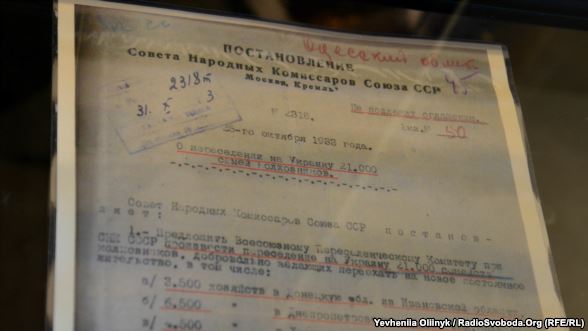

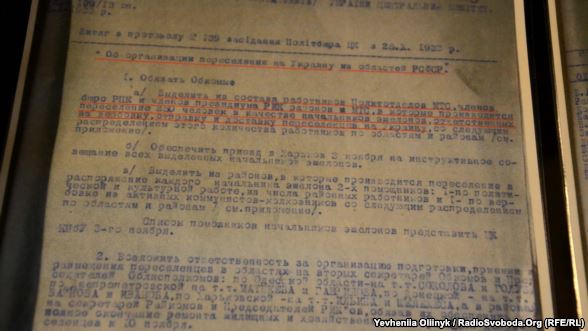

1. Secret decision on population resettlements in Ukraine by the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR.

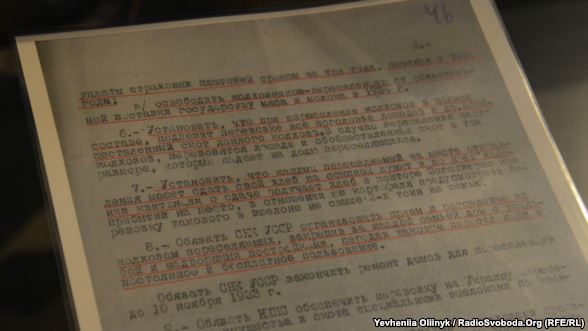

2. Secret decision on population resettlements in Ukraine.

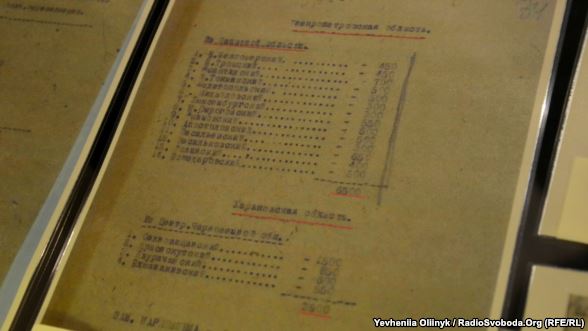

3. Planned distribution of settlers on Ukrainian territories.

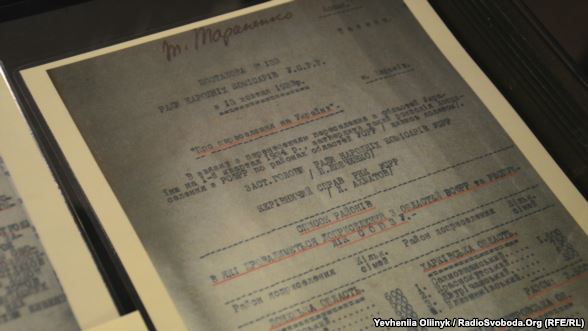

4. Politburo decision on reception of Russian migrants in Ukraine.

5. Secret decision to resettle 21,000 Russian families to Ukraine.