"Within a year of occupation Crimea turned into a peninsula of fear," said Ukraine Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights Valeria Lutkovska during the 113 th session of the UN Committee on Human Rights on 16 March 2015. The native population of Crimea, the Crimean Tatars, have much to fear: only a little over 20 years has passed since they returned from a forced deportation to Central Asia under the Soviet dictator Stalin. They are now facing the danger of a second deportation off their native land. On 26 March 2015, leader of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis Refat Chubarov said that after Russia's occupation of the peninsula, the Crimean Tatars "do not exclude any action on the part of Russia, including the deportation of whole nations." The year under Russian occupation has been one of relentless repressions against Crimea's indigenous population. Halya Coynash at KHPG has been documenting all the cases; we have placed them on one timeline.

1. Kidnappings and murders

A total of 18 Crimean Tatars were reported missing in Crimea over this year, as reported by Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev. Some of them were found dead, some were contacted later. The Crimean Tatars were one of the most active opposers of the Russian occupation; they had been staging multiple protests from the time of the appearance of unmarked military personnel in Crimea (who Putin later admitted to be regular Russian troops).

Reshat Ametov was the first Crimean Tatar to die: he was kidnapped on 3 March 2014 from the building of the Crimean parliament where he was standing in solitary protest by three men from the so-called ‘self-defence’ paramilitaries. His mutilated body was found on 15 March. The Crimean Human Rights Field Mission reports that the murder investigation has been suspended, with no reason given.

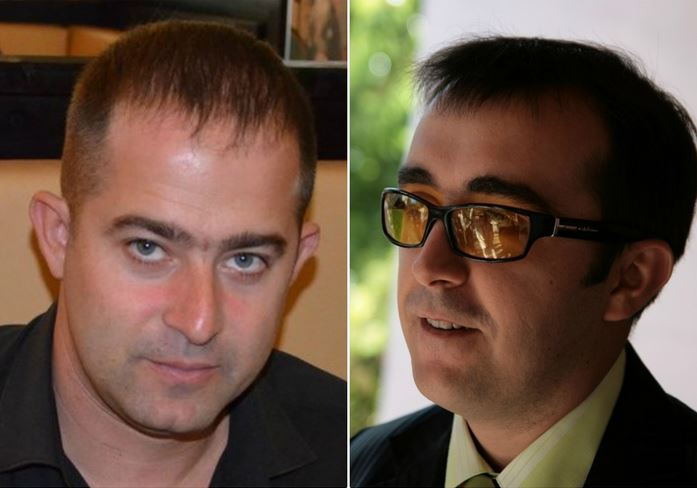

Timur Shaimardanov, a 34-y.o. businessman, and Seyran Zinedinov, a 33-y.o. hauler, close associates that participated in demonstrations against annexation of the Crimea and helped the Ukrainian military during the blockage of their military units by the "self-defense" and "little green men," disappeared in May. On 25 May 2014, Timur Shaymardanov left for work, and nobody saw him ever since. His friend Seyran started a search for him, but went missing after 5 days. Criminal cases for murder were opened, but, according to relatives, the investigators were more interested in the political views of the victims than their whereabouts.

On September 27, the 18-year-old Islyam Dzhepparov and his 23-year-old cousin Dzhevdet Islyamov were kidnapped by unknown men in black uniforms. Law enforcement agencies have shown negligence in searching for the victims; relatives suspect that they themselves are involved in the crime.

23-year-old Eskender Apselyamov disappeared in Simferopol on 3 October 2014 after leaving for work. 25-year-old Edem Asanov was found dead a week after his disappearance on September 29. On October 13, two 18-year-old students, Artem Dayrabekov and Belyal Bilyalov, disappeared in Simferopol. Bilyalov's body was found on the outskirts next evening with signs of cruel torture. 29-year-old Usein Seitnabiyev had been missing since 31 October 2015.

Apart from Crimean Tatars, other civic activists have been kidnapped in Crimea: Vasyl Cherysh, an Automaidan activist who left for Crimea when Russian forces disguised as "self-defense" troops began seizing government buildings, was already reported missing on 15 March 2014, a day before the so-called "referendum." Leonid Korzh had gone missing a couple of days before Shaimardonov. A more extensive report is available on gordon.com.ua.

2. Destroying the leadership

On 20 March 2015, at a meeting of the UN Security Council, Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev explained the repressions among Crimean Tatars: it was because Russia could not find the equivalent of Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov in annexed Crimea. Although separate Crimean Tatar individuals have opted to cooperate with the new Russian authorities, their representative body, the Mejlis, and Crimean Tatars in general, were strongly against Russian occupation and have faced mounting repression.

Refat Chubarov and Mustafa Dzhemilev banned entry to Crimea

On 22 April 2014, veteran Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev was first informed of a five-year ban to enter Crimea, a ban that Russian authorities claimed was false. However, when Mustafa attempted to cross the border between mainland Ukraine and Crimea on 3 May 2014, he was stopped by a cordon of frontier guards and military men and was handed in a handwritten paper banning him from entering Crimea. Five thousands of Crimean Tatars on one thousand cars gathered to the frontier city of Armyansk to greet their leader and accompany him into Crimea, chanting his name and the slogan "Millet! Vatan! Kyrym" ("Nation! Homeland! Crimea") (as seen on video). With the risk of bloodshed great, Mustafa Dzhemilev returned to Kyiv, but the Mejlis called upon Tatars to continue peaceful protests. On May 15, Mustafa Dzhemilev's house was searched, and in February 2015, a Russian court upheld the ban, imposing that the veteran Crimea Tatar leader is a "threat to Russia's national security." Mr.Dzhemilev's son is on trial in Russia and being charged with a more serious offence than should be appropriate, which suggests he is being used as a hostage.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzIRHFwVBDA]

Head of Mejlis Refat Chubarov faced a similar fate on 5 July 2014. Crimean "Prosecutor General" Nataliya Poklonskaya issued both leaders a 5-year ban on entering Crimea, until 2019.

The Mejlis is an executive commission, the 33 members of which are chosen by the Crimean Tatar Kurultai, an elected representative council that is the highest political authority of the Crimean Tatar nation, from among Kurultai delegates. The Kurultai is elected every five years by an election mechanism created and run by the Crimean Tatars themselves. Read more: Mejlis explainer on RFERL

An offensive against the Mejlis

After the sham "referendum" by which Russia annexed Crimea, veteran Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev instructed the Crimean Tatar Mejlis, located in the capital of Crimea Simferopol, to keep flying the Ukrainian flag. This was quickly put to an end when 40 armed men from the so-called local "self-defense" forces removed it on 22 April 2014, injuring 3 women. Later, the Mejlis representatives were handed a warning against extremist activities. So began the era of repressions against the Medjlis and its representatives. Nataliya Poklonskaya threatened to dissolve the Mejlis if it did not stop its "extremist activities" after the Crimean Tatar protest against Mustafa Dzhemilev's ban to enter Crimea.

The major offensive on the Mejlis began on 16 September, when an 11-hour search by the Russian FSB resulted in confiscation of the Mejlis minutes, religious books and personal items belonging to Mustafa Dzhemilev. The next day, on September 17, the Mejlis and Crimea Fund that is providing it its premises in Simferopol was ordered to "evacuate" the building within 24 hours.

The following day the Fund was fined 50 000 rubles (around $1 200) for failing to accomplish this impossible task. The Fund's assets and bank accounts were frozen on fabricated charges. The story ended with the Mejlis leaving the building, the Crimea Fund being fined for 4,5 mn rubles, and facing charges of not administering proper care to the building of historical value. Rize Shevkiev, the head of the Crimea Fund, which is the main charity of the Crimean Tatars, is also facing a fine of 350 000 rubles and has had a criminal investigation opened against him. The new occupation authorities headed by Sergey Aksyonov have ignored the Mejlis' proposals on establishing relations/dialogue. Aksyonov had been quoted as saying that he does not plan to speak with the Mejlis until it is registered as an NGO, which is unacceptable to the Crimean Tatar community.

There is another Mejlis located in the historical capital of the Crimean Tatars, Bakhchysarai. The Bakhchysarai Mejlis, like the central one in Simferopol, is also facing eviction from its building after a mysterious court hearing that no member of the Mejlis heard about.

Every member of the Mejlis can expect a search of his home. - Deputy Mejlis Head Nariman Dzhelyal

Head of the Mejlis Refat Chubarov continues to lead it from Ukraine's capital Kyiv, where he is forced to live after the 5-year banned imposed on him, but the Russian occupation authorities do not cease to repress leaders of the Crimean Tatar community. Deputy Head of the Mejlis Akhtem Chiygoz has been arrested on surreal charges of "organizing mass disturbances" against the seizure of the Crimean Parliament on 26 February 2014 - weeks before Russia illegally annexed the peninsula. On 7 May 2015 he had gone on hunger strike in protest of solitary confinement punishment cell. Over the last year, repressions of Mejlis members have become a regular activity: as newly elected Deputy Mejlis Head Nariman Dzhelyal said after his 5-hour interrogation on 28 March 2015, “Every member of the Mejlis can expect a search of his home.”

3. Repressions and persecution

Freedom of assembly dismissed

On 16 May 2014, head of the puppet government in Crimea Sergey Aksenov banned mass assemblies in the center of Simferopol, on the eve of the Crimean Tatars' annual commemoration of the anniversary of Stalin's deportation of their people in 1944, celebrated yearly on May 18. The Mejlis held the celebrations on the outskirts of the city, but the meeting was obstructed in every possible way. The annual celebration of the Day of the Crimean Tatar flag in Simferopol on June 26, the demonstration dedicated to the pan-European Day of Remembrance of Victims of Stalinism and Nazism on August 23, and the action timed to the International Day of Human Rights on December 10 were all forbidden. Moreover, the new Crimean occupation government has even erected a monument to the Soviet dictator Stalin responsible for evicting 180 000 Crimean Tatars from their native Crimea, sparking outrage from the Tatar community and has even proposed that the Day of Deportation be celebrated as a day of joy, which it now is - April 21 is officially designated as a festive day in Crimea. The occupation government is now attempting to split the Crimean Tatar community by organizing celebrations that the Mejlis has decided not to hold. Under the atmosphere of kidnappings, deportations, and persecution, the Mejlis had ruled that the traditional May 3 Crimean Tatar Spring Festival Hyderlez is inappropriate, as there is nothing to celebrate. However, the occupation authorities organized it instead; the Mejlis had called upon the Crimean Tatars to ignore this provocatory event; however, there was an attendance of around 5000.

In 2015, the Crimean Tatars are being restricted once again from honoring the memory of their ancestors forcefully deported from their homeland once again. Just as last year, the occupation authorities are announcing that "according to their sources" alleged terrorist threats from unnamed Ukrainian extremists and Mejlis members are planned on May 18. Two Mejlis members have received formal warnings that meetings are unacceptable. Mustafa Dzehmilev considers that this constitutes an effective ban on the commemoration. At the same time, the Crimean occupation authorities are making moves to glorify the Soviet dictator that deported the Crimean Tatars in 1944, opening memorial plaques and monuments to Stalin, mirroring Russia's growing cult of the bloody dictator.

Harassment and searches

Mejlis members were and are continuously being threatened by men in camouflage, who claim to be representatives of the same "self-defense forces." On 7 May 2014, Mejlis member Abduraman Egiz was assaulted in Simferopol. Ismet Yuksel, General Director of the Crimean News Agency [QHA] and adviser to the head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar on relations with Türkiye, was banned entry into Crimea for five years similar to Mustafa Dzhemilev. Mejlis members are regularly harassed at the border between mainland Ukraine and Crimea - Gayana Yuksel and Emine Avamileva are two recent examples. Crimean Tatar scholar Nadir Bekir was prevented from attending a UN General Assembly special session on indigenous peoples when a group of people in balaklavas stopped the taxi in which he was heading to catch a plane to the conference and took away his passport and mobile phone (it's noteworthy that the same story repeated with small ethnic groups representatives, citizens of Russia, attempting to leave for the same conference - passports taken away, cars stopped). But searches in homes of regular Crimean Tatars and participants of protests have also become commonplace.

Two politically motivated cases for repressions: the "February 26" case and "May 3" case

The Crimean Tatars were among the most vocal and active opposers of the Russian occupation of Crimea. On 26 February 2014 they organized a rally outside the Crimean parliament with which they tried to prevent it seizure by unmarked armed men, under the barrels of guns of which the racketeer known by the nickname of "Goblin" and head of local Russian Unity party Sergey Aksyonov proclaimed himself the "prime minister" of Crimea. A year later, Russian authorities are prosecuting Crimean Tatars for participating in this protest that took place under Ukrainian rule and Ukrainian legislation in a case of exemplary legal nihilism. To date, four activists have been arrested. Notably, the first one was Deputy Head of the Mejlis Akhtem Chiygoz; arrests of Asan Chebiyev, Talyat Yunosov, and Eskender Emirvaliyev followed suit. Eskender Nebiyev, a cameraman for the silenced TV channel ATR, was jailed for his coverage of the protest in April 2015. A The Crimean Human Rights Field Mission has condemned the so-called ‘February 26 Case’ as legally unfounded and politically motivated, aimed solely at persecuting those who oppose the Crimea occupation regime.

The "May 3 case" is another politically motivated case for arrests of Crimean Tatar activists that protested Mustafa Dzhemilev's ban on entering Crimea at Armiansk, a city at the border with mainland Ukraine. Four Crimean Tatar activists have been arrested so far, and others have had their homes searched. The so-called prosecutor of Crimea, Natalia Poklonskaya, claimed that the protest was of an "extremist nature" and sent two reports to the Russian Investigative Committee and FSB to start a criminal prosecution of the protesters. According to Alexandra Krylenkova from the Crimean Human Rights Field Mission around 200 people were fined between 10 and 40 thousand rubles on administrative charges over an "unauthorized rally" and "not obeying the police." Nataliya Poklonskaya, the puppet "prosecutor general" of Crimea, is coming up with creative ways to persecute Crimean Tatars: recently, one Crimean Tatar man has been charged with using violence on May 3 towards the same Berkut police officer that was the alleged victim of another prosecution story where a Ukrainian activist was jailed for 4 years.

...and even deportation!

Sinaver Kadyrov, a Crimean Tatar activist that refused to accept Russian citizenship, had been essentially deported from Crimea. For Ukrainians that refused Russian passports, staying legal means, as "foreigners," crossing the border to mainland Ukraine every 90 days to have a stamp in their passport. Sinaver Kadyrov had one, but the Russian courts have "their own mathematics," as his wife commented. An appeal was submitted, but it was dismissed by the court. Sinaver Kadyrov's case is the first official deportation of Crimean Tatars from their homeland.

4. Silencing dissent: crackdown on Crimean Tatar media

And of course, media that stir up hysteria and give some citizens hope that Crimea will return to Ukraine, thus carrying out destructive activities – the actions of such channels and their work will definitely not be welcome on the territory of the republic. What do we need hostile media for - who stir up the population and untruthfully cover the situation? - Sergey Aksyonov, "Prime Minister" of Crimea

The so-called "self-defense" forces (read: Russian troops in disguise) had abducted and beaten up founder of the Crimean Internet channel CrimeanOpenCh Osman Pashayev on 20 May 2014, after which he left the peninsula. Ismet Yuksel, General Director of the Crimean News Agency [QHA] had been banned entry to the peninsula for years on 9 August 2014. Crimean Tatar newspapers citing decisions of the Mejlis to boycott upcoming elections in occupied Crimea were labeled as "extremist;" such words as "annexation," "occupation," and "temporary occupation of Crimea" are also considered extremist.

Media outlets in Crimea are required to obtain a Russian license before the beginning of April 2015. Many of them are not getting it; the self-installed Prime Minister Sergei Aksyonov's remarks about not needing media channels that cover events "inaccurately" leave little room for doubt: this is a planned campaign to silence voices disagreeing with the Russian occupation of Crimea. Right now, the following media outlets are endangered in Crimea: the children’s Crimean Tatar TV channel Lyalya and radio station Meidan FM, as well as the Internet site 15 mins; the official newspaper of the Mejlis, or Crimean Tatar representative assembly Avdet; the children’s educational journal Armanchyk, and QHA – the Crimean News Agency.

But perhaps the case that is most outrageous is the silencing of the world's only Crimea Tatar TV channel ATR, which is counting hours before it will be forced off-air. Despite appeals from ATR and the Crimean Tatars, as well as Russia's Human Rights Council to Russian President Vladimir Putin to ensure that the channel is not driven out of Crimea, the channel was stripped of its broadcasting licence on April 1. Crimean Tatar leaders were warned to not protest, and searches of leaders and arrests of activists continue. A former ATR cameraman's house was searched, and another cameraman has been jailed for coverage of the 26 February 2014 protest, being the sixth arrest so far in the row of "February 26" cases. Two underage students are facing heavy fines for trying to make a film in support of ATR during the protest.

The main tendencies of pressure on freedom of speech and free expression in Crimea have been summed up by the Crimean Field Mission for protection of human rights in this infographic:

[hr]Many thanks to Eugene Linetsky for contributing to this article and to Halya Coynash for documenting all the cases of repressions