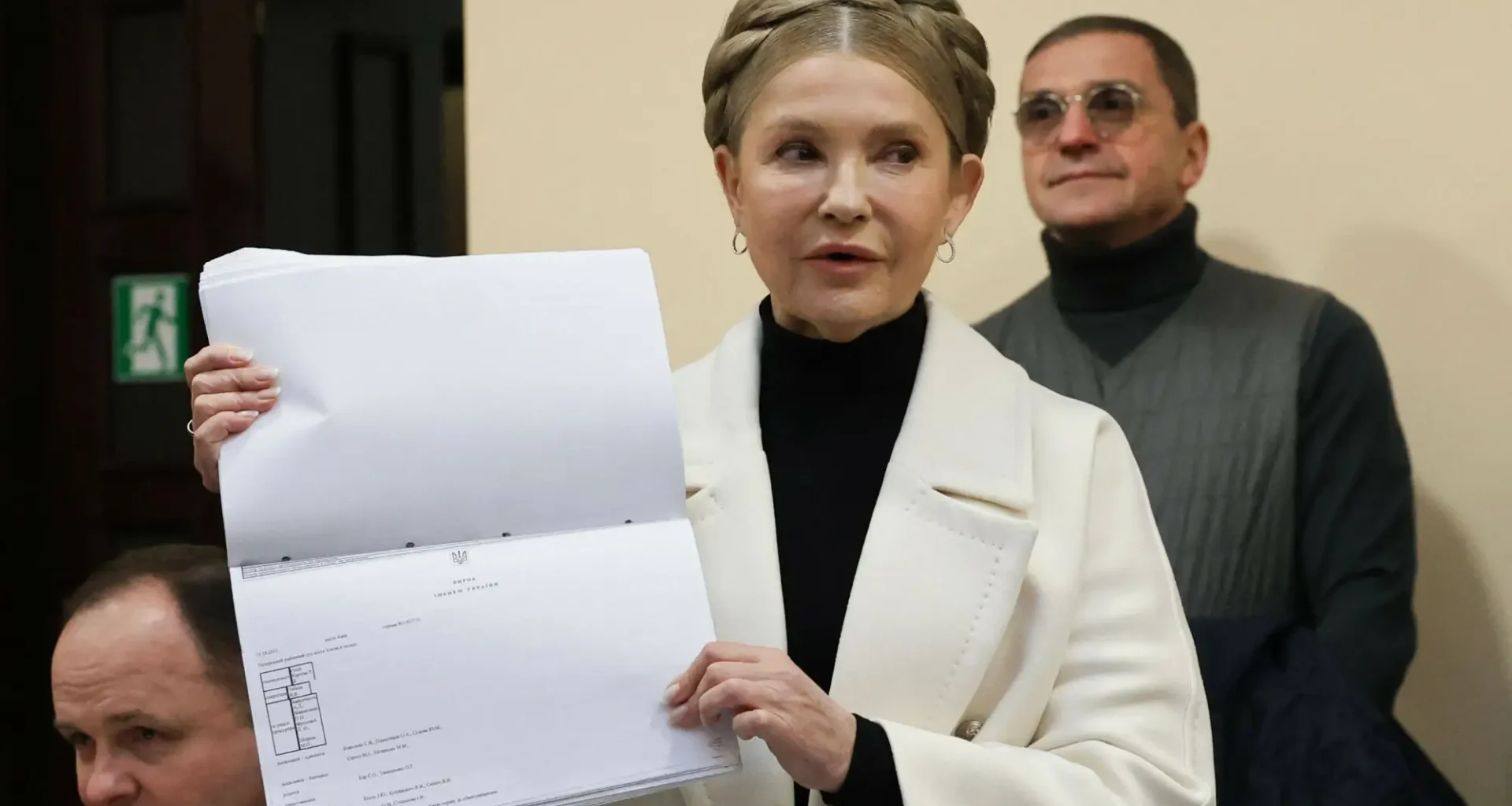

In July 2025, Yulia Tymoshenko stood at a parliament podium and called gutting Ukraine's anti-corruption agencies "the brightest day in this parliament." She dismissed reformers as "grant patriots" who "need to work off their grants." Her Batkivshchyna faction voted almost unanimously for legislation that would have stripped NABU and SAPO of their independence.

Six months later, those same agencies charged her with buying MPs' votes.

"That 'brightest day' has now turned into perhaps the darkest for her political career," Oleksandr Salizhenko, editor-in-chief of the civic watchdog Chesno, told Euromaidan Press.

What she's accused of

NABU alleges Tymoshenko offered lawmakers $10,000 monthly for "loyal behavior during voting"—not one-off payments but a "regular cooperation mechanism" with advances.

The agency published audio recordings and what it describes as instructions she allegedly sent to an MP, directing votes on cabinet appointments. The stated goal on the recordings, according to LB.ua: to "kill" the ruling majority.

Tymoshenko insists the recordings "are a completely fabricated recording" and demands an expert examination. She compared the overnight raid on her party headquarters to the Yanukovych era, when she was imprisoned on charges the West called politically motivated.

"I will be here until the country is freed from this, in essence, fascist regime," she told the court.

To understand how Ukraine's former "Joan of Arc" ended up here, you need to understand her three-decade journey through Ukrainian politics—and the system she helped build.

The gas princess

Tymoshenko's political career began inside the system she would later rail against.

In the mid-1990s, her company UESU held a near-monopoly on Russian gas imports—a position granted by Prime Minister Pavlo Lazarenko. The business earned her the nickname "the gas princess." US federal prosecutors later documented $101 million in transfers from UESU accounts to Lazarenko's offshore holdings.

Lazarenko was convicted in California and ranked among the World Bank's ten most corrupt officials globally. Tymoshenko was never charged—a US judge declined to include her, partly because Russia refused to provide evidence.

She was first elected to parliament in 1996. By 1999, she was deputy prime minister for fuel and energy. In 2001, she was fired, arrested, and briefly jailed on corruption charges. The charges were later dropped; Tymoshenko maintained they were politically motivated.

The Orange Revolution

— Photo by igorgolovniov

Tymoshenko reinvented herself as a revolutionary.

She co-led the 2004 Orange Revolution that overturned Viktor Yanukovych's fraud-tainted presidential victory, earning comparisons to Joan of Arc for her fiery speeches in Kyiv's Independence Square. Her signature braided hairstyle became a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. Forbes ranked her the third most powerful woman in the world in 2005.

She became Ukraine's first female prime minister in January 2005, serving until September of that year, then returned to the post from December 2007 until March 2010.

But constant disputes with President Viktor Yushchenko—her Orange Revolution ally—fractured the pro-Western coalition. Their inability to deliver on promises of European integration and economic growth helped fuel Yanukovych's political comeback.

Prison and rehabilitation

Tymoshenko lost the 2010 presidential race to Yanukovych by 3.5 percentage points. The following week, parliament voted no confidence in her government.

Then came the prosecution. In 2011, she was convicted of "abuse of power" over a 2009 gas deal with Russia and sentenced to seven years in prison.

The United States called her a "political prisoner." Sweden's foreign minister labeled it a "political show trial." The European Union made her release a condition of Ukraine's association agreement. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch expressed concern that the charges did not constitute crimes.

She was freed in February 2014 following Yanukovych's ouster during the Revolution of Dignity, wheeled out of prison to address the Maidan crowds.

But the political comeback never materialized. She finished third in the 2019 presidential race with 13.4%. Recent polling puts her at roughly 6%—trailing both Zelenskyy and former Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi by wide margins.

The word she made famous

For decades, Ukrainian oligarchs controlled parliament not through ideology but through purchased loyalty. Lawmakers who switched factions for money were derided as "tushky" (carcasses).

The term entered Ukrainian politics in 2010, when Tymoshenko was accused of trying to buy MPs to save her coalition after losing the presidential race to Yanukovych. She denied it then. Now she faces formal charges of the same practice—with audio recordings.

"This is a long-forgotten practice—one form of political corruption from previous parliamentary terms—and it's directly connected to Yulia Tymoshenko herself," Salizhenko told Euromaidan Press. "Now we see an irony of fate—the same practice has returned."

Coordinating how MPs vote isn't inherently corrupt—every parliament has party whips who enforce discipline. "There's nothing wrong with coordinating lawmakers in a chat or verbally," Salizhenko said. "It's different when money enters the equation. That's political corruption."

The practical harm

When the ruling party has 227 MPs and never achieves full attendance, every vote becomes precarious. This creates a market. Important wartime legislation—defense procurement, energy policy, mobilization—becomes subject to whoever can pay.

"We noticed over the past year that Batkivshchyna appeared among the leaders in supporting government votes," Salizhenko said. "This can be seen as Batkivshchyna's attempt to become the ally that the majority can rely on."

The arrangement appeared mutually beneficial: Zelenskyy's Servant of the People got reliable votes when its majority wobbled; Batkivshchyna got influence disproportionate to its 25 seats.

A shifting rhetoric

Tymoshenko has consistently attacked international advisory boards that help select anti-corruption officials as "external governance" threatening Ukrainian sovereignty.

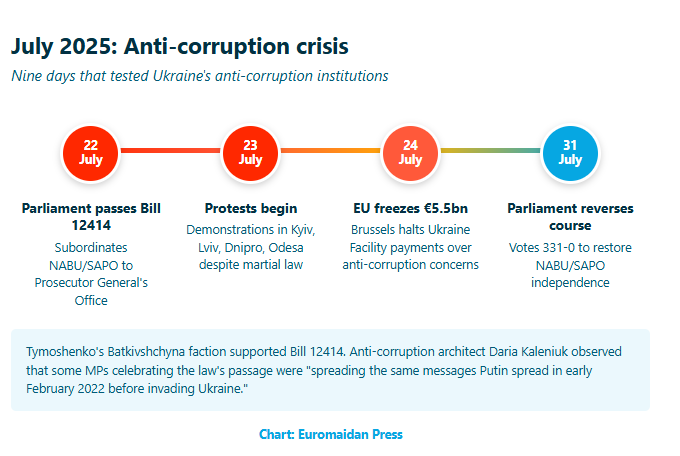

When parliament voted in July 2025 to subordinate NABU and SAPO to the Prosecutor General's Office, street protests erupted in Kyiv, Lviv, Dnipro, and Odesa—remarkable given martial law restrictions on public gatherings. Within a week, parliament voted 331-0 to restore the agencies' independence.

Tymoshenko's faction then registered an alternative bill, positioning herself as defender of what she had voted to destroy days earlier.

"Over recent years, she's changed her rhetoric," Salizhenko told Euromaidan Press. "It now closely resembles pro-Russian talking points—very close to the banned Opposition Platform for Life, especially on NABU, SAPO, and the Istanbul Convention."

VoxUkraine found that Tymoshenko and Batkivshchyna MPs spread more misinformation about supervisory board reforms than almost any other faction—alongside the remnants of pro-Russian parties. When the party's reform voting record was analyzed, it ranked last among the five pro-European factions in parliament.

The system she helped build

Ukrainian political culture has evolved since Tymoshenko's rise. "Button-pushing"—MPs voting on behalf of absent colleagues—vanished after biometric voting was introduced. Vote-buying sums have shrunk. Street protests can reverse bad laws within days.

"The political culture is definitely changing," Salizhenko said. "But this case shows the practice wasn't fully eradicated. It's returned in a modified form."

Even the price of corruption has fallen. In the Yanukovych era, bribes ran into hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. The December 2025 bust revealed payments of $2,000-20,000.

"Everyone was surprised by the change in sums," Salizhenko noted.

Some analysts question whether prosecution benefits Tymoshenko more than it hurts her. At 6% in polls, she has no realistic path to power—but criminal charges give her a platform and remind her base she exists. "The political system is more complex than a black-and-white picture," Salizhenko said. "Everyone plays this game and tries to grab as much as possible from any crisis."

Whether this case constitutes persecution or prosecution will be determined by evidence yet to be fully tested in court. But there is a certain symmetry: the woman who emerged from Ukraine's oligarch system, reinvented herself as a revolutionary, then tried to gut the agencies investigating her—is now being prosecuted by those same agencies.

On day 1,422 of Russia's full-scale invasion, they're testing whether she's untouchable. The answer appears to be no.