Staunton, December 24 – Ethnic Russians living in Latvia and Lithuania “view themselves as a community and respect Russian culture but consider their native home to be the countries where they live rather than Russia,” and this is true even of those born in Russia or who are not citizens of their countries of residence, according to a new study.

The study, entitled “The Identity of the Russian Ethnic Group and Its Expression in Lithuania and Latvia,” was prepared by Arvidas Matiulionis of the Institute of Sociology of Lithuania and Monika Frejute-Rakauskiene of Ethnic Research of Lithuania, has been published in “Mir Rossii: Sotsiologiya, Etnologiya” of the Moscow Higher School of Economics.

The two scholars compared the ethnic self-definitions and identities of the Russian ethnic group in Lithuania and Latvia. They defined ethnicity as “a community or identity based on common origin and a feeling of solidarity,” as opposed to a people which they argue is “to a greater extent connected with language, cultural and ideological” considerations.

They conducted deep interviews with ethnic Russians of various generations and waves in both countries and supplemented that with polling data gathered by ENRI-VIS.

Ethnic Russians living in Latvia and Lithuania, they point out, are “immigrants of various historical periods,” ranging from those who fled religious persecution before 1917 to those who were transferred there during the Soviet occupation. According to the 1989 census, there were 906,600 Russians in Latvia (34 percent of the population) and 345,400 Russians in Lithuania (9.4 percent).

After the recovery of independence in 1991, Russians in Lithuania could gain Lithuanian citizenship if they sought it and had worked and lived there for two years before applying. According to the 2011 census, 99.3 percent of the residents of the country have Lithuanian citizenship, including the overwhelming majority of ethnic Russians.

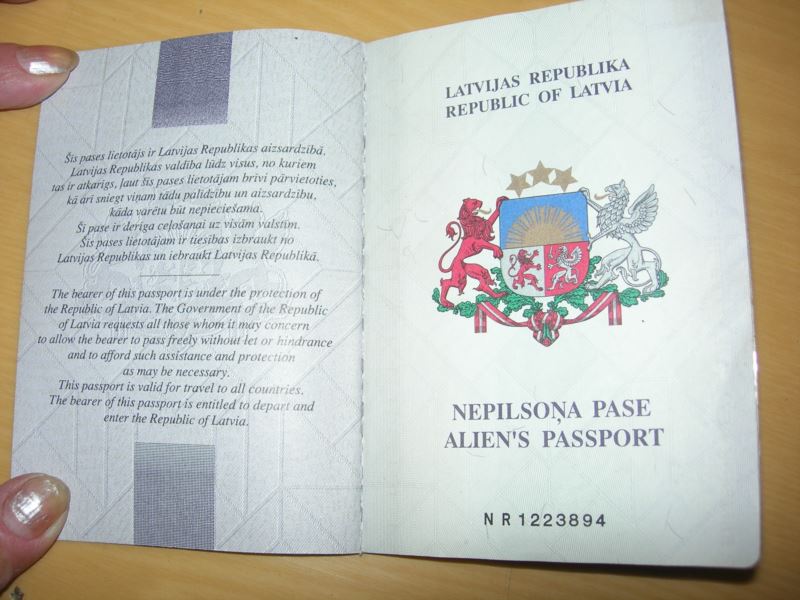

The situation in Latvia was more complicated because Riga insisted on its rights to deny citizenship to anyone moved in by the occupation authorities. But over time and under pressure from the EU, it has modified that stance and now has created several paths by which the overwhelming majority of ethnic Russians there can achieve Latvian citizenship.

According to the 2011 census, the two scholars report, 83.5 percent of the residents of Latvia are Latvian citizens. That means that 14.2 percent are still non-citizens, the vast majority of whom are ethnic Russians.

Polls show, Matiulionis and Frejute-Rakauskiene say, that “the younger and middle generation of Russians born in Lithuania identify themselves more with Lithuania than with Russia. And even those Russian-speaking residents of Lithuania who were born on another territory all the same consider Lithuania their native home.”

In Latvia, they report, the differences between citizens and non-citizens is “more marked.” But at the same time, “even those non-citizens who were born in Latvia identify with it and not with Russia and especially with the place in which they live.” Few in either country say they would leave even if guaranteed economic security.

Equally interesting, the scholars found that while some ethnic Russians reported ethnic tensions based on language or culture in each country, none of them said that they had been subject to discrimination because of their language or ethnicity.

And while polls showed that ethnic Russians living in Lithuania “identify themselves with Russia as their historical Motherland,” representatives of the younger generation do so “not so much with the country as with Russian culture.” Ethnic Russians born in Latvia “consider Latvia their motherland, although they consider themselves Russians by ethnic origin.”

“Frequently,” the two researchers say, “those respondents born in Latvia in general do not feel ties with Russia and do not have friends or relatives there.” Moreover, members of the younger generation, even those who identify as Russians, make a clear distinction “between Russians living in Russia and Russians in Latvia and feel themselves linked not to Russian Russians but to the community of Russians of Latvia.”

“Ethnic identity is important for all generations of Russians in Lithuania and Latvia,” they conclude, but that must be evaluated in terms of the fact that “in all generations of Russians questioned in Latvia, local identity predominates: the informants connect themselves with the street on which they live and with the city as well.”

“Even non-citizens, born in Latvia have [this] local identity,” they say. And thus while some may feel an attachment to Russia on a cultural level, they consider Latvia – and also Lithuania – as their motherland, even if they continue to “think in Russian” while speaking the national languages well.

Image: RFE/RL