Russian neo-imperialistic propaganda has been claiming that the annexation of Crimea is a form of “historical justice.” Perhaps, most famously, in his March 16th speech during an event in the Kremlin formalizing the annexation, Vladimir Putin stated that “Crimea has always been an integral part of Russia.” Even though this claim is laughable (Crimea was a part of Russia for 204 years, 37 of which it spent in Soviet Ukraine, while the independent Crimean Tatar state existed there for almost 3.5 centuries, and the Byzantines ruled Crimea for 650 years), it is still an example of truly dangerous rhetoric that could trigger endless conflicts around the world. Perhaps the most vulnerable to that kind of reasoning is Russia itself, with vast territories once taken from her neighbors over the years.

Novgorod Republic

Originally a part of Kyivan Rus, Novgorod was founded in the late 10th century and enjoyed de facto independence since the 11th century, a century before Moscow was founded. With public assemblies and elected officials playing a central part in its politics, Novgorod was arguably the first example of a democratic government within modern Russia. A bustling northern trade hub, Novgorod controlled vast territories of what is now the Russian north.

Novgorod was conquered and annexed in 1478 by the Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan III, whose grandson Ivan the Terrible became the first Tsar of all the Russias. In a symbolic gesture Ivan III took down the Novgorod bell used to call Veches (public assemblies), ending Novgorodian republican traditions. Still, Novgorod has not been ruled from Moscow for almost half of its millennial history.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Founded by Lithuanian Baltic tribes in the 11th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, at its peak in the early 14th century, included territories of modern Belarus, Latvia, and Lithuania, and parts of Estonia, Moldova, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine. It was a multicultural Christian state that ruled over vast lands in what is now Western Russia. Their control of Russian Orthodox lands did not sit well with Moscow, which aimed to “reunite” all the territories of the former Kyivan Rus. These territories were conquered by the Tsars in a series of wars with Lithuania and later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth spanning over a century. The best-known episode of these conflicts is the 1514 battle of Orsha, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian force of 30,000 defeated a Muscovite army of 80,000 men.

The Battle of Orsha is a defining historical moment for Belarusian nationalists, who trace their origin to the Grand Duchy. Recently, Belarusian president Aliaksandr Lukashenka denounced the Russian annexation of Crimea and reminded Putin of Belarusian claims to the lands of Bryansk and Smolensk, the latter transferred from the nascent Soviet Belarus to Russia in 1919, mirroring the transfer of Crimea.

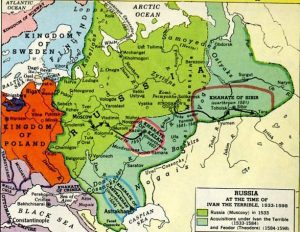

The Tatars

By the 16th century, the once-great Golden Horde was fractured into several warring khanates. The rulers of Muscovy, once appointed by the Khan, had overthrown their Tatar overlords and looked to the East. In 1552, Ivan the Terrible captured, sacked, and nearly destroyed Kazan, forcing the Tatars out. Astrakhan, although originally intended to be annexed peacefully by installing a pro-Russian khan, eventually suffered the same fate in 1556, and its capital Xacítarxan never recovered. The Tatars of Siberia Khanate were also conquered by conquistador-like Cossack forces during Ivan IV’s reign in 1582.

It should be noted that the Tatars at that point were not foreign newcomers, but a mixture of a broad number of indigenous peoples with the Mongol elites, much like how the Normans and Saxons eventually formed the English ethnicity. Under Russian rule they endured Christianization and forced eviction from their lands, resulting in a number of uprisings that were often brutally quelled by Russian troops. Presently, some of these peoples enjoy local autonomy in name only, with Moscow’s grip on the “national republics” as tight as any Russian region.

The Caucasus

The Russian conquest of the Caucasus is perhaps one of the most gruesome parts of early modern Russian history. The wars that lasted from 1817 to 1874 were characterized by fierce resistance, punitive actions, and ethnic cleansings, the most well-known of the latter occurring during the conquest of Circassia in the North Caucasus. Modern Circassian activists label these events as the “Circassian Genocide” and were recently outraged by the Sochi Olympics being held in the ancient Circassian lands.

During the war, Russia saw the first wave of Islamic insurgency in history, which was waged by Imam Shamil for decades. History repeated itself one and a half centuries later, when the crackdown on Chechen separatism (accompanied by numerous atrocities by the Russian military) sparked a wave of jihad across the Caucasus that has continued until the present, occasionally spilling into Russia proper. Holding Chechnya came at the cost of hundreds of civilian Russian lives and billions transferred from the federal budget as effective tribute to the Caucasus autonomous republics, including the Chechen dictator Kadyrov, himself a former insurgent, and his cronies and clansmen. This policy has repeatedly come under fire from even the most die-hard Russian nationalists, their popular slogan being “Stop feeding the Caucasus!” A Russian nationalist intellectual, Konstantin Krylov, was sentenced to 120 hours of correctional labor for urging the “end this weird economic system.”

China

The Russian-Chinese border clashes started in the 17th century, during the Russian colonization of Siberia. At that time Russia failed to gain the lands north of the Amur river, which forms the modern Russian-Chinese border. Numerous treaties confirmed Chinese sovereignty over territories of modern Southeastern Russia (known in Russian as Priamurye and Primorye).

In the 19th century, when China fell on hard times and was forced to fight most European powers in the Opium wars, the Russian Empire threatened to open a second front in the north and annexed the territories north of the Amur river and the Pacific coast, later legitimized by the Treaty of Aigun. Islands on the Amur river became the battleground of Sino-Soviet border conflicts in the 1970s, and fears of an overpopulated China reclaiming the vast and sparsely settled Amur region still sour Russian-Chinese relations.

Japan

Perhaps the most well-known Russian territorial dispute is the one with Japan over the Pacific Kuril islands. In the 19th century, exploration and settlement of the Kurils and Sakhalin by the sprawling Russian Empire and modernization of Meiji Japan happened almost simultaneously. The Treaty of St. Petersburg in 1875 formalized Japanese control over the Kurils in exchange for dropping claims to Sakhalin. After the Russo-Japanese war, which ended in disaster for Russia and sparked the first Russian Revolution, southern Sakhalin came under Japanese control and remained that way for another 40 years.

In the last months of the Second World War, the Soviet Union denounced their non-aggression pact with Japan and attacked Japanese-held Manchuria, Korea, and the Pacific Islands. The Japanese-settled Kurils were invaded and occupied by Soviet marines, and the Japanese villagers were forced out. Later, these acquisitions were legitimized by post-war Allied conferences. However, Japan views the four southern Kuril islands as not covered by those treaties and maintains the claim to them to this day, which has led to the failure to negotiate a formal Russian-Japanese peace treaty 70 years after the war.

East Prussia

Another dubious post-WW2 Russian acquisition was the “Kaliningrad Oblast” – a part of German East Prussia, with its capital of Konigsberg, renamed to Kaliningrad in honor of Soviet figurehead Mikhail Kalinin. Since 1618, the German-settled East Prussia was part of the Duchy of Brandenburg, which later became the Kingdom of Prussia and eventually formed the modern German state. While East Prussia was briefly claimed by Russia during the Seven Years’ War in the 18th century, by the time of WW2 it had been a part of Germany for more than three centuries. The 1945 annexation was followed with forcible expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Germans from their homeland, only the magnificent Prussian architecture remaining as a reminder of Kaliningrad’s former inhabitants.

Modern Kaliningrad recently served as a great example of Russia’s hypocrisy and double standards in dealing with separatist movements inside and outside of Russia. In an apparent mockery of Russian flags hoisted in Crimea and Donbas, on March 11, 2014 the German tricolor was raised over the garage of the local Federal Security Service department. The three young men who performed this act are now facing long prison sentences under Russia’s new anti-separatism laws.

Ukraine

The vast majority of modern Ukraine was not ruled from Moscow before the 17th century, while the Ukrainian-speaking population inhabited lands stretching far to the east of the modern Russian-Ukrainian border. These territories, comprising modern Russian Kursk, Belgorod, Rostov, and Krasnodar regions, were claimed by the Ukrainian People’s Republic that declared independence from Russia in 1918.

Some of those lands were ceded from Soviet Ukraine to Russia in 1919-1924, including several rural districts and the cities of Belgorod and Taganrog, despite their population being Ukrainian-speaking. Judging by Russia’s logic, Ukraine could send troops to those regions anytime Russia is thrown into a crisis.

Granted, all these claims based entirely on historical precedent may seem laughable and certainly not an excuse for a partition of Russia. However, Putin’s claims to Crimea and “Novorossiya” are no less laughable, yet they resulted in thousands of deaths and Russia’s rapid slide into a diplomatic and economic crisis. The moral, perhaps, is that historical claims are a thing of the past and definitely should not play any role in present-day international politics.