In a small bakery on the edge of Yeghegnadzor, Gohar shapes her cupcake into a makeshift map. "Armenia is landlocked," she explains, pressing her finger into the dough. "Of the four countries surrounding us, we have only one ally: Georgia. The rest—" she gestures at the edges, "Azerbaijan, Türkiye, Iran—are and always will be around us." Her simple pastry demonstrates the precarious position of a nation seeking to break free from Russian influence.

On 1 January 2025, Russia began withdrawing its troops from Armenia, ending a military presence that has defined the South Caucasus since 1992. In the border regions, where Armenian and Azerbaijani soldiers eye each other across 150-meter gaps, an unspoken rule prevails: nobody talks about the Russians. This silence speaks volumes about a nation grappling with newfound sovereignty and redefining its security landscape amidst persisting tensions with Azerbaijan.

Life on the frontline

"You can see the front line from here," says Maarten, pointing toward desert mountains where a large Azerbaijani flag flutters above a small fort. Soldiers stand silhouetted against watchtowers and trenches, never taking their eyes off the enemy. Sporadic clashes regularly break out along the border between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. The latest clashes—less than 3 kilometers from the village of Armash—took place on 11 September.

From his home, Maarten watches what he calls "the incessant ballet of troops." A resident of the small municipality and former truck driver, he returned to live in the village after the 2020 war.

"It's very dangerous to live here," he says, his eyes fixed on the arid landscape. "Armenia is my country," he repeats, as if the words themselves could fortify the border.

When asked about the visible Russian military presence—checkpoints and military barracks—he falls silent. He doesn't want to talk about it. Nobody wants to talk about it in the village. It's a sensitive topic here. The area is militarized, and journalists are not allowed in.

We had to follow the border between the two countries—still at war—to reach Yeghegnadzor. The road winds through a complex military geography: dozens of Armenian bunkers and outposts line the left side; Azerbaijani positions and trenches mirror them on the right.

The route crosses the Karki territory—an Azerbaijani exclave controlled by Armenian forces since 1989—a remnant of the USSR's collapse. Russian watchtowers—once symbols of protection—now prepare for departure, their presence a reminder of Moscow's fading influence in the region.

City at the crossroads

Yeghegnadzor—population 8,000 and 15 kilometers from the Azerbaijan border—is the capital of the Vayots Dzor province, one of the regions Russia began to leave on 1 January 2025. All over town, Armenian soldiers patrol the streets while armored vehicles hide in the heights. The military presence is heavy but subtle, like the tension in the air.

Along these same roads where Russian patrols once dominated, EU Mission in Armenia (EUMA) vehicles now cruise past, their twelve-star flags a stark contrast to the Russian insignia they replace. Sometimes, they pass Russian military convoys heading north—a visible change of the guard that symbolizes the broader transformation of regional security dynamics.

In her shop on the edge of town, Gohar, a pastry cook, explains the situation: "The Russians are no longer our allies. They say they protect us, but they haven't protected us. That's why we want to turn to our European friends."

Resentment against Russia's presence has taken hold.

"The Russians say they're helping us, but they're not," she says with bitterness. "They just want to have a foothold in the Caucasus."

Gohar, Armenian pastry cook

The great withdrawal

The agreement came after careful diplomacy. On 9 May 2024, Hayk Konjoryan, the parliamentary leader of Armenia’s governing Civil Contract party, announced Russia's departure from the strategic regions of Syunik, Vyats Dzor, Gegharkunik, and Ararat—essentially Armenia's entire border zone with Azerbaijan.

Hundreds of Russian troops will depart from positions they've held since 1992, marking a significant rift between the two former allies. The announcement came one day after Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow to discuss "the most important bilateral issues and regional issues."

"Armenia views the withdrawal as a victory in its strategy to assert sovereignty and independence after years of subservience to Moscow," explains Richard Giragosian, Director of the Regional Studies Center in Yerevan. This represents Armenia's first public demonstration of autonomy from Russian dominance since the USSR's collapse.

Breaking from Moscow: from alliance to abandonment

The path to this moment began with betrayal.

Armenia's ties with Russia, which date back to Soviet times, were strengthened after joining the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 1992. A 1997 treaty of friendship, cooperation and mutual assistance further cemented these bonds. But the relationship began to crack during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war when Russian peacekeepers stood by during Azerbaijani advances.

"The CSTO's failure to act during the Nagorno-Karabakh war highlighted Russia's passivity, eroding Armenia's trust in Moscow as a reliable security partner," says Richard Giragosian.

Russian soldiers deployed as an interposition force remained impassive in the face of Azerbaijani advances, leaving civilian populations to their fate. This passivity provoked widespread criticism against Moscow, which was accused of prioritizing its strategic interests at the expense of its Armenian ally.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 further aggravated the situation. The rapprochement between Moscow and Baku, to the detriment of Yerevan, reinforced Armenians' feeling of abandonment.

"The weakening of Russia's position, following its invasion of Ukraine, has created an opportunity for Armenia to reorient its foreign policy more effectively," analyzes Giragosian.

Moscow's revenge playbook

"A weakened but vengeful Russia could seek opportunities to reassert its influence in the South Caucasus," warns Giragosian, "particularly if its position in Ukraine continues to deteriorate."

The potential tactics mirror those seen elsewhere in the post-Soviet space.

Armenia’s key land trade routes go through Georgia, where Russia still holds leverage over transit corridors like the Upper Lars crossing. Moscow could restrict cargo movements, impose new tariffs, or orchestrate "border security concerns" to slow Armenian exports.

Signs of this scenario are beginning to materialize. At the Darial Gorge, where Russia meets Georgia, kilometers of trucks regularly pile up along the road. This artery linking Russia and Georgia to the South Caucasus demonstrates Moscow's continued control over vital trade routes.

"Due to Western sanctions over the war in Ukraine, access to eastern markets became a key aspect of Russia's foreign economic policy," notes researcher Irakli Sirbiladze.

This approach—using infrastructure and economic ties as pressure points—becomes more crucial as military influence wanes. The strategy mirrors tactics seen elsewhere in the post-Soviet space, where Russia maintains influence through economic and infrastructure dependencies even after military withdrawal.

Energy is another potential pressure point. Armenia still relies on Russian gas, with Gazprom controlling nearly all of its imports. Moscow could increase prices, cut supply, or impose "technical issues" as a pressure tactic—similar to its gas diplomacy with Ukraine and Moldova.

Political destabilization is yet another one. The Kremlin has long relied on pro-Russian factions in Armenia’s opposition. Figures like Robert Kocharyan, a former president and close Moscow ally, have already criticized Pashinyan’s Western tilt. A well-timed Kremlin-backed opposition push—through protests, disinformation campaigns, or even economic sabotage—could weaken the government’s resolve.

Moreover, Armenia's smoldering conflict with Moscow's closest partner in the South Caucasus, Azerbaijan, provides the Kremlin with endless opportunities for security sabotage. If Russia wants to punish Armenia, it doesn’t need to act directly—it can simply "look the other way" as Azerbaijan escalates along the border. The absence of Russian peacekeepers creates an opportunity for Baku to test Armenia’s defenses, forcing Yerevan to reconsider its reliance on European diplomacy over Russian military backing.

Ukraine knows first-hand the devastation of Russian revenge for pursuing independence.

This is why, for 11 years, Euromaidan Press has covered freedom movements in post-Soviet countries — and now, you can be the force that drives our mission.

Stop watching history. Create it — become our patron right now.

Armenia's Western pivot

Since then, Armenia has been trying to distance itself from Moscow and find other allies, turning in particular to the European Union and the United States. "Armenia's distancing from Moscow predates the war in Ukraine but has been reinforced by Russia's military incompetence and its inability to meet Armenia's security needs," says Giragosian.

Armenia has taken unprecedented steps toward independence:

- Joint military drills with US forces

- Humanitarian aid to Ukraine

- Hints at potential EU membership

- Plans to leave the CSTO

Even so, the country remains highly dependent on Russia, with which it is linked by a treaty of friendship, cooperation and mutual assistance dating back to 1997. Their ties, which date back to Soviet times, were strengthened after Armenia joined the CSTO in 1992, which Yerevan now claims to want to leave.

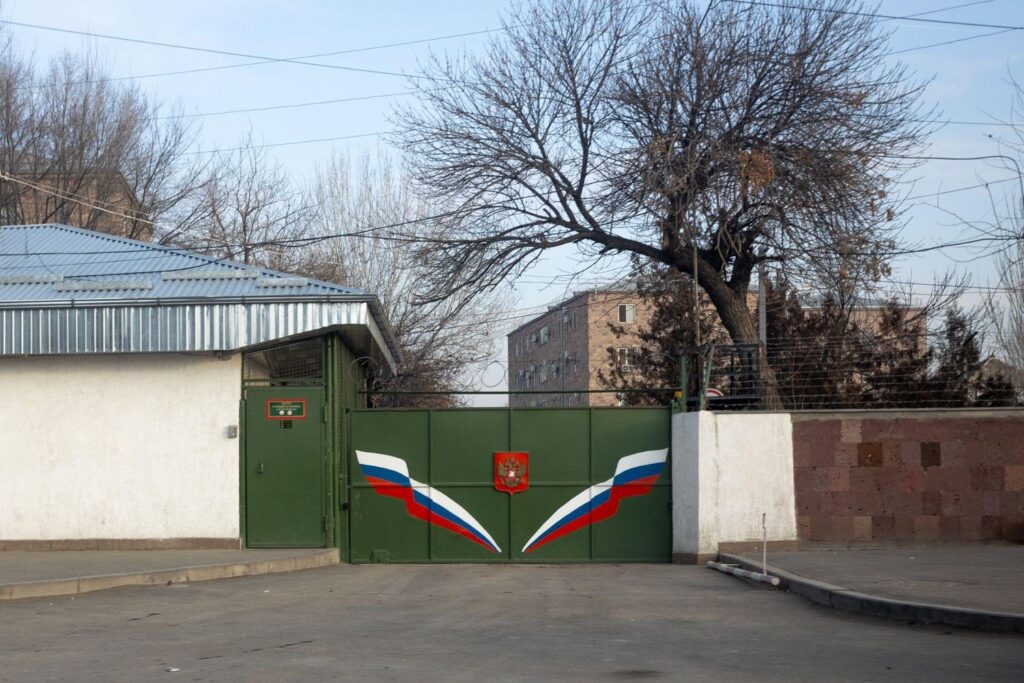

A Russian watch tower in the province of Ararat © Théo Prouvost

The European alternative

Russia’s withdrawal, once unthinkable, has left a noticeable gap in Armenia’s security landscape—one that the EU has begun to fill. This European turn can be felt with the presence of the EU Mission in Armenia (EUMA) everywhere in the provinces neighboring Azerbaijan.

On several occasions, we pass trucks flying the European Union flag with the twelve golden stars. Sometimes they pass Russian military convoys.

EUMA’s presence has been pivotal in stabilizing the tense border regions.

"We patrol along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border and conflict-affected areas to build confidence and improve security," explains Ingrid Mühling, a communication expert for the EU mission. "We have 40-50 patrols in a week, covering around 1000 kilometers. The number of incidents has been reduced, but there is a chance of incidents like small arms fire from unknown directions. Our patrols must always stay focused and attentive. The difficult landscape—mostly mountains—is challenging too."

Despite these challenges, the EU's engagement has resonated locally. "We've seen that our presence has improved security, and we feel that people support and trust us," said Mühling. "This is proof that our presence is needed."

The mission's outreach, including visits to schools and meetings with local communities, has further bolstered its credibility, fostering a sense of partnership. "We are here on the invitation of the Armenian government, and we cooperate with Armenian authorities," says Mühling. This comprehensive approach marks a stark contrast to Russia's purely military presence.

For many Armenians, the EU's growing role offers a sense of reassurance amidst uncertainty.

"Every time there are observers, we feel a little safer," shared Gohar in Yeghegnadzor. "That's why we want the Europeans to be our allies."

"The EU's deployment of monitors in Armenia is unprecedented, signaling a shift in regional influence," remarked Giragosian.

For a country historically tied to Moscow, this pivot underscores Armenia's determination to assert its sovereignty and diversify its security partnerships.

By deploying civilian monitors and championing democratic reforms, the EU is emerging as a credible alternative to Moscow's fading grip.

"The EU continues to support democratic reforms, aiming to prevent backsliding and solidify Armenia's independence," says Giragosian. "The EU is unlikely to replace Russia entirely but can help Armenia diversify its security partnerships."

A nation at the crossroads

As evening falls in Yeghegnadzor, Gohar's bakery fills with the smell of fresh pastries. Outside, an EU patrol vehicle passes silently, its headlights illuminating the empty Russian watchtower on the hill.

However, the future is fraught with tension. Unlike NATO allies, Armenia does not have a formal security guarantee from the EU or the US. While the EU Mission in Armenia (EUMA) provides monitoring, it lacks any military mandate. If Azerbaijan launches a large-scale attack, European patrols will not stop tanks. Armenia is betting on Western support—but it is unclear if the West will back that bet when it matters most.

Azerbaijan, emboldened by its 2023 victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, has little incentive to halt border provocations. With a stronger military, growing oil wealth, and Turkish backing, Baku could seize this moment to press territorial claims—especially if Russia does nothing to stop it.

Iran has long opposed Western influence in the South Caucasus. Tehran tolerated Russian troops in Armenia but may view a growing EU presence as a threat. While open conflict is unlikely, Iran could seek to undermine Armenia’s Western shift through economic coercion or covert support for destabilizing actors.

The question remains: can Armenia's pivot to Europe bring stability to this volatile region, or will the vacuum left by Russia's retreat create new tensions? For now, however, one thing is clear: Armenia is no longer content to remain in Russia’s shadow and is determined to chart its own course, surrounded and with few allies. .

As the sun sets over the mountains, the silhouettes of soldiers still stand guard, but the flags they watch have changed. Armenia's experiment in independence has begun, and the world is watching to see if this small nation can successfully navigate between empires without provoking new tensions in an already fragile region.

For now, the Russian watchtowers stand empty. But in the South Caucasus, no power vacuum lasts for long.

With contributions by Alya Shandra

Related:

- Armenia deepening relations with US, EU, considers joining EU, FM says

- Armenia, Azerbaijan breakthrough signals end of Russia’s South Caucasus influence

- Armenia participates in Ukraine peace formula summit for the first time

- Armenia ratifies ICC Rome Statute, opening path to arrest Putin