Just six days before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, almost 1,000 children from occupied Donetsk and Luhansk institutions were told they were going on an “excursion” or an “adventure” to Russia.

These actions were justified as an “evacuation” from an alleged imminent threat from Ukrainian forces - a narrative Russia has repeatedly used to legitimize its aggression against Ukraine. However, this wasn't a humanitarian evacuation - it was the beginning of a systematic state-sponsored program to erase Ukrainian identity through forced deportation and adoption.

Ukrainian authorities have identified nearly 20,000 children who have been forcibly taken from occupied territories to Russia, though the real numbers are likely much higher. Many deportations remain undocumented or concealed, making it impossible to assess the true scale of these forced transfers.

Behind these numbers are stories of individual trauma.

Vika (name changed for security) faced an impossible choice: accept placement with a Russian family or be separated from her younger siblings.

Lyubov only discovered she could not return to Ukraine after arriving at her new Russian "home." She thought this was all temporary.

Gleb initially clung to hopes of returning to Ukraine. Eventually, he resigned himself to his new reality, saying he had no one to return to.

Masha, separated from her friends after being taken from a Luhansk orphanage, retreated into isolation and withdrawal.

All these stories were uncovered by the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL), which conducted a months-long investigation and identified 314 documented cases of Ukrainian children forcibly relocated to Russia. The researchers believe this number represents only a fraction of the total cases.

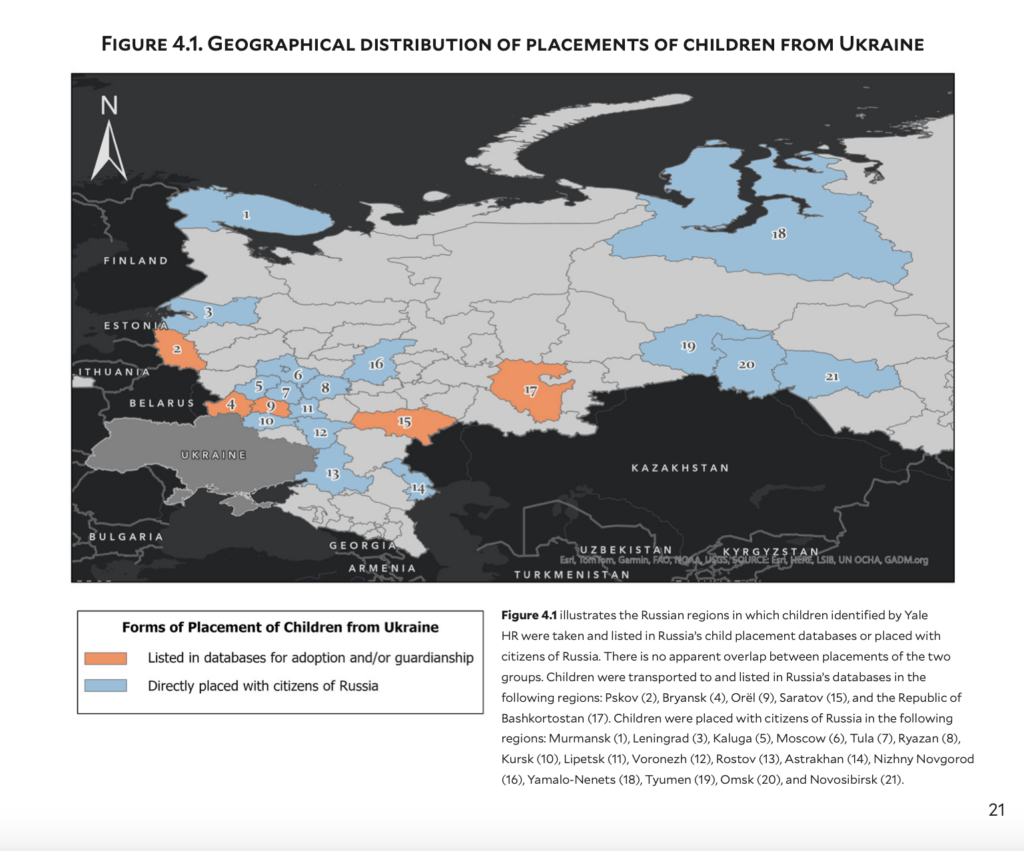

The children were dispersed across 21 Russian regions. While the investigation primarily documented cases from Donetsk (80.4%) and Luhansk Oblasts, evidence suggests this practice extends far beyond these regions.

The investigation, which analyzed satellite imagery, flight records, Russian government documents, and social media posts, reveals sophisticated state machinery involving Putin's presidential fleet, military bases, and a network of officials from local administrators to the Kremlin itself.

What emerges is not a story of humanitarian aid but a carefully orchestrated program of cultural genocide in slow motion: children as young as two were stripped of their Ukrainian citizenship, given new Russian identities, and subjected to "re-education" programs designed to make them "good Russian soldiers."

These children aren't just being moved - they're being reprogrammed to forget who they are.

This report adds substantial evidence to the International Criminal Court's case against Vladimir Putin and his Children's Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova, who already face arrest warrants for the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children. But it goes further, exposing how Russia systematically changed its laws, funded databases, and created bureaucratic procedures to separate Ukrainian children from their heritage permanently.

The findings are particularly crucial now, as time works against reunification efforts - young children's memories fade, documentation disappears, and those who've reached adulthood in Russia face increasing complications in contemplating return to Ukraine.

Putin personally commands child deportation machine

The findings reveal that Vladimir Putin personally directed the program of transferring Ukrainian children from its inception, orchestrating coordination between the Kremlin, the United Russia party, and occupation authorities in so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics (DNR and LNR).

At the heart of this operation is Maria Lvova-Belova, Putin's chosen executor for the entire program. Her involvement was comprehensive, ranging from coordinating with occupation authorities to personally accompanying children on military transport flights and conducting citizenship ceremonies.

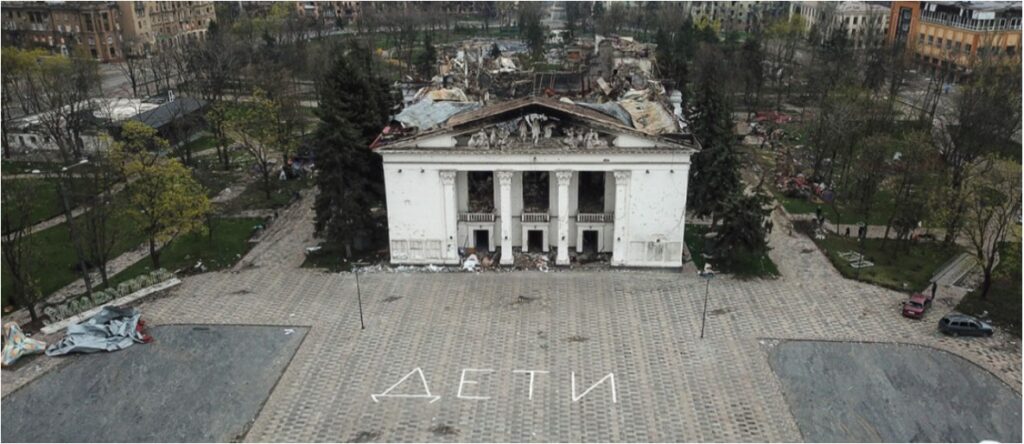

The scale of the operation became evident during the siege of Mariupol in 2022, when 31 Ukrainian children, aged 7 to 17, were taken from basements and transported on a plane from Putin's presidential fleet. In a symbolic gesture demonstrating her dedication to the program, Lvova-Belova adopted a 15-year-old boy from this group.

Between April and September 2022, she expanded the deportation network from one Russian region to fourteen, personally escorting groups of children by train and plane to their new families.

However, as international scrutiny intensified, her public stance shifted dramatically. Following US sanctions and International Criminal Court (ICC) indictments, she began denying the adoption of Ukrainian children, instead claiming they were merely under guardianship and "could return home if they wanted."

With 324 of 450 seats in Russia's parliament, Putin's United Russia party established headquarters in occupied territories by April 2022 to provide a bureaucratic framework for operations and synchronize policies.

The Ministry of Education managed the operational aspects – maintaining databases, overseeing re-education programs, and running institutions housing the children. They even prepared "international" agreements to legitimize the transfers before the territories' official annexation.

Throughout the operation, Putin, however, remained the central authority while his subordinates executed the intricate details of permanently severing these children from their Ukrainian heritage.

Russia's laws erase every link to Ukraine for displaced children

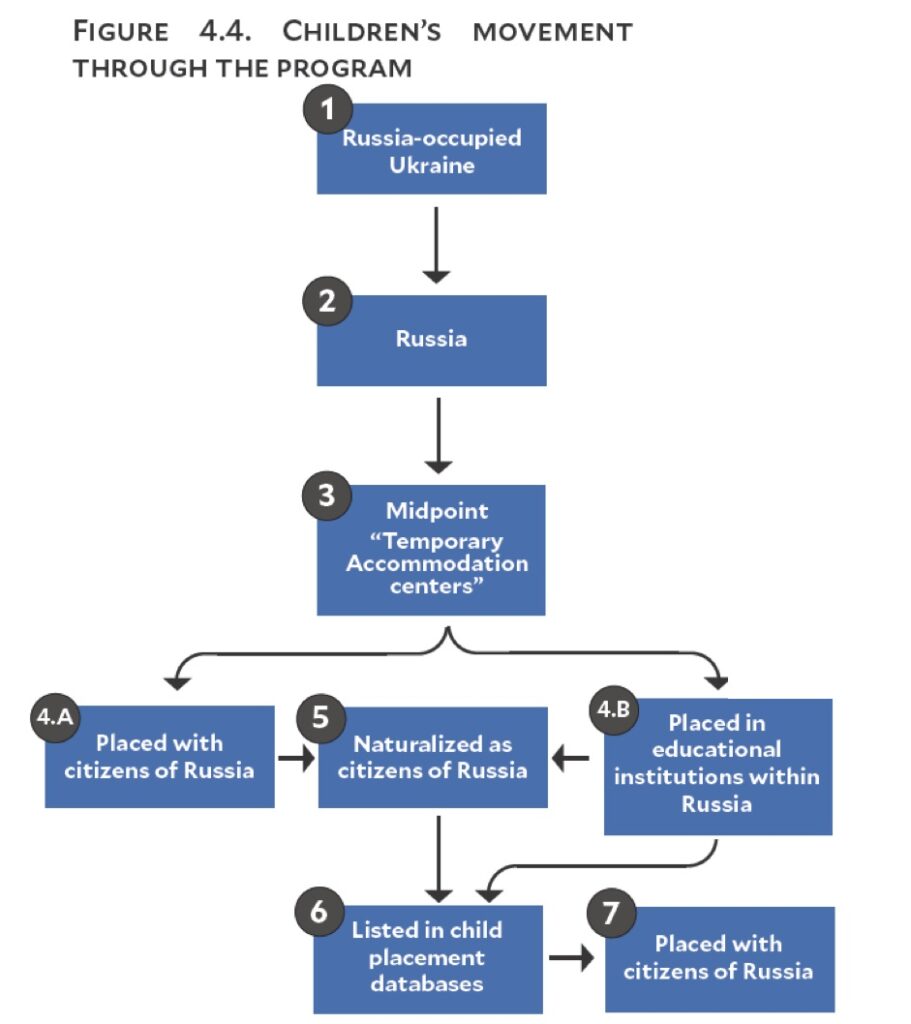

Upon arrival in Russia's Rostov and Kursk oblasts, Ukrainian children were placed under "temporary guardianship" – a designation that masked a systematic pipeline to permanent adoption by Russian families. This occurred despite most children having living parents and relatives in Ukraine, having been placed in institutions primarily due to family hardships.

Russia's pre-2022 legal framework would have prevented this systematic transfer of children, as it required consent from both the child's legal representative and their home country's authorities for any adoption. This obstacle needed to be removed once Ukraine was designated an enemy state.

The transformation began with a crucial meeting on 9 March 2022 between Putin and his children's rights commissioner, Maria Lvova-Belova. Putin's directive was unambiguous: bypass "bureaucratic delays" and prioritize the "interests of children." The very next day, Lvova-Belova initiated the process by signing a protocol with officials from occupied territories.

The legal transformation happened in several waves:

- 30 May 2022: Putin issued a decree simplifying Russian citizenship for orphans

- 26 December 2022: Another decree enabled the renunciation of Ukrainian citizenship for children under 14 without their consent

- 18 March 2023: The Russian parliament (State Duma) passed legislation making citizenship renunciation unilateral, eliminating the need for Ukraine's approval

- 28 April 2023: A new law established that dual citizens would be recognized solely as Russian

- 4 January 2024: Putin's final decree extended simplified naturalization to all Ukrainian children.

Russian children’s placement databases systematically erased the children's Ukrainian origins, presenting them as Russian-born. By March 2023, they had even incorporated annexed Ukrainian territories as Russian regions for child placement.

Adoptive parents also gained the power to completely alter a child's identity – including name, patronymic, date, and place of birth – and could register themselves as birth parents with new birth certificates.

The six-month "temporary guardianship" period provided Russian authorities sufficient time to grant children Russian citizenship, after which they could be permanently adopted with their Ukrainian identity completely erased through legal name and document changes. Government employees were legally bound to maintain silence about these adoptions.

This systematic erasure of Ukrainian children's identities violated the Geneva Conventions, as Russia refused to register these children with Ukraine or the International Committee of the Red Cross, effectively severing their ties to their homeland.

Russia forces Ukrainian children to become "Russian"

At least 67 identified children received Russian citizenship, with 13 being awarded Russian domestic passports in ceremonial presentations.

This citizenship wasn't merely symbolic – it became a prerequisite for accessing essential services, including medical care and education. Yale researchers documented at least one case where a child was denied medical treatment until becoming a Russian citizen.

The "re-education" component proved particularly disturbing. All eight facilities housing these children exposed them to pro-Russian propaganda, including military education, where children handled weapons and attended "military-patriotic" events.

In Bashkortostan, a Russian republic, one program explicitly aimed to "cultivate a desire to be like strong Russian soldiers." Children handled military equipment and were recruited for cadet schools, with Russia's Investigative Committee creating a special "quota" for orphans.

At least three identified children were placed with families of Russian officials or military personnel. One child, Sergey, appeared in databases in November 2022 before being placed with a Russian soldier's family.

Military recruiters regularly visited institutions housing Ukrainian children, delivering lectures about "the importance of preparing for military service," suggesting a deliberate pipeline to future military service against their own homeland.

The chaotic rush to place children with Russian families

Yale's Humanitarian Research Lab documented 166 Ukrainian children directly placed with Russian families across 16 regions following the full-scale invasion.

Maria Lvova-Belova claimed 380 children were placed, suggesting Yale's verified 166 cases represent only a fraction of the total.

The placement process revealed a stark contrast between careful planning and chaotic implementation.

In Novosibirsk, one foster mother received just five days' notice before children from Luhansk arrived. Another family promised three girls and two boys but received four girls and one boy instead.

In a particularly disturbing case, Moscow officials reportedly forced a woman to accept children despite her initial refusal due to health concerns.

Misinformation plagued the process. Families frequently received incorrect details about the children, including undisclosed health needs. Some children endured multiple relocations, passing through three different regions before reaching their final placement.

Russia's actions meet definition of genocide

Under the Rome Statute, Russia's actions meet all five elements of war crimes. The program involved taking protected persons (Ukrainian children) during an armed conflict and moving them across borders without legitimate justification.

While international law does allow for “evacuations” in some cases, there's a catch - you can't evacuate people from a crisis you created yourself. Furthermore, such evacuations must be temporary and preserve family unity – conditions Russia systematically violated.

More critically, international law required Russia to return these children once fighting ceased and ensure they maintained their cultural identity. Instead, Russia implemented an aggressive "Russification" program and pursued permanent adoptions.

The deportations relied on deception – children were misled about "excursions," forcibly separated from families, and placed in a system designed to erase their Ukrainian identity. Even parents who provided consent faced an impossible choice, pressured to choose between their children's safety and permanent separation.

High-ranking officials, including Putin himself, actively created laws and systems to facilitate these transfers.

The genocide question, while more challenging to prove legally (no one has ever been convicted of genocide specifically for transferring children), presents compelling evidence:

- Systematic erasure of Ukrainian citizenship

- Forced Russian naturalization

- Mandatory "re-education" programs

- Prohibition of Ukrainian language and culture

- Placement with Russian families authorized to change children's identities

- Deliberate concealment of Ukrainian origins in databases.

This program transcends "humanitarian adoption" – it represents a systematic attempt to erase Ukrainian identity in the next generation. The crucial distinction lies in intent and method: these children are being forcibly taken, their identities erased, and their connections to Ukraine systematically destroyed – all hallmarks of genocide under international law.

Time is running out for bringing Ukrainian children home

The report also outlines five crucial steps needed to bring Ukrainian children home:

- Russia must provide a complete register of all children in its custody

- Ukraine must create a framework for their return

- both countries must agree on the logistics

- Ukraine needs to determine what happens to children without guardians

- returned children must receive comprehensive support for reintegration.

Time poses perhaps the greatest threat to reunification efforts. Young children's memories fade rapidly, crucial documentation vanishes, and investigation trails grow increasingly cold.

Despite these obstacles, law enforcement must continue investigating this systematic program, civil society must maintain documentation efforts, and international agencies must intensify their scrutiny.

The message is clear: Russia must share all available information about these children with Ukrainian authorities and international organizations. Until then, each passing day makes reunification more difficult for children caught in this web of systematic displacement.

Read more:

- Over 3,000 children from occupied Kherson Oblast taken to remote areas of Russia for "re-education" – Ombudsman

- Russia plans to relocate 5,000 Ukrainian schoolchildren from occupied Luhansk Oblast

- Ukraine is searching for nearly 20,000 children deported by Russia; real numbers could be much higher

- US imposes sanctions on Russian officials involved in deportation of Ukrainian children