Among them was Andriy Babiuk, aka Myroslav Irchan, a Ukrainian-Canadian writer, poet, novelist, publicist, playwright, translator, literary critic, journalist, historian and publisher. He was one of the many Ukrainian-Canadians who voluntarily left Canada and returned to Ukraine, believing in the slogans of the Communist government and seeking to contribute to the development of the Ukrainian SSR.

Like most returnees, who did not manage to escape again, he paid for this decision with his life.

Myroslav Irchan’s real name was Andriy Babiuk. He was born into a poor peasant family in the village of Piadyky, today’s Kolomyia Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast on July 14, 1897. He studied in the village school and in the Kolomyia Gymnasium, and graduated from the teacher’s seminary in Lviv in 1914.

During World War I, Irchan served in the Legion of Sich Riflemen of the Austro-Hungarian Army. He joined the Communist Party of Ukraine in 1921, ended up in the ranks of the Red Ukrainian Halytska Army (the official name of the Ukrainian Halytska (Galician) Army (UHA) after its forced absorption into the Red Army in February 1920), and edited its periodical Chervony Strilets (Red Rifleman).

At the end of the civil war, Irchan settled in Kyiv, where he joined the editorial board of Halytsky Komunist. He met and married a young lady called Zdenka, who was the daughter of a Czech doctor. When her parents returned to Prague in 1922, the young couple followed them. In Prague, he enrolled at Charles University and participated in Ukrainian student activities.

In October 1923, Irchan accepted an invitation through the ULFTA (Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association) to come to Canada and undertake editorial and organizational work for the Ukrainian pro-communist left. The ULFTA was a cultural and educational Communist organization that sought to provide industrial and agricultural workers and their families with a wide variety of services. It established libraries, drama groups, orchestras, choirs, and fraternal organizations that offered medical and social assistance.

In Canada, Irchan experienced the most creative literary period of his life as editor, poet, storywriter and playwright. The first play he wrote in Canada between 1923-24 was The Family of Brushmakers (Родина щіткарів).

He settled in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where he published in local left-wing newspapers, edited two Ukrainian magazines - Working Woman (Robitnytsia) and World of Youth (Svit Molodi), and founded the writers’ group Zaokeansky Hart (Overseas Hart), which was affiliated with the Kharkiv-based proletarian writers’ organization Hart. Irchan was a staunch Communist and felt quite at home in the Ukrainian-Canadian community, where the left-wing movement was quite popular.

From 1923-1933, the Communist Party of Ukraine introduced a series of policies called “Ukrainization”, dedicated to enhancing the national profile of state and party institutions and thus legitimizing Soviet rule in the eyes of the Ukrainian population. The measures included enhancing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of Ukrainian culture in various spheres of public life, such as education, publishing, government and religion.

Many Ukrainians, who had emigrated abroad, took up the Communist call, and Myroslav Irchan was one of them. In the summer of 1932, sincere in his belief of building a Communist Ukraine, Irchan returned to Kharkiv, then the capital of Soviet Ukraine, where he headed the organization of Western Ukrainian Communist émigré writers Zakhidna Ukraina and edited its monthly journal. The group included many intellectuals from Halychyna - Volodymyr Hzhytsky, Dmytro Zahul, Mechyslav Hasko, Liubomyr Dmyterko, Agata Turchynska, Myroslav Sopilka. Irchan resided in the famous community centre – the Slovo Building in Kharkiv. He continued his creative work, wrote five plays, and was widely published in newspapers and magazines.

However, Ukrainization was short-lived. By late 1929 the Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin, had begun a systematic process of political repression. Members of the intelligentsia were arrested as “enemies of the people.”

Myroslav Irchan was apprehended on December 28, 1933 and accused of belonging to a nationalist, Ukrainian counter-revolutionary organization. Three months later, on March 28, 1934, a judicial “troika” (three officials who issued sentences to people after simplified, speedy investigations and without a fair public trial) and the Separate Council of the GPU sentenced the writer to ten years in a maximum security penal colony. Irchan’s arrest was met with shock and disbelief by the rank-and-file of the ULFTA in Canada, and questions regarding the entire matter played a crucial role in the development of a major rift with Communism and reshuffling in the Canadian organization.

Myroslav Irchan served his sentence in the labour camps of Karelia and in the Solovki Gulag on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea. It is here that he met Ukrainian playwrights Les Kurbas and Mykola Kulish, who shared the same tragic fate.

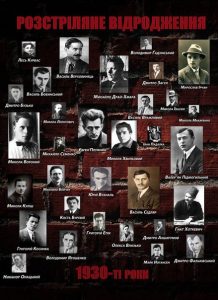

On October 9, 1937, the NKVD “troika”of Leningrad Region sentenced Myroslav Irchan to death - “execution by shooting” - in a fabricated case against 134 so-called “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists”, who had allegedly founded a counter-revolutionary organization called the All-Ukrainian Central Bloc. Myroslav Irchan was executed with many other Ukrainian intellectuals on November 3, 1937 at Sandarmokh in Karelia, RF (Executed Renaissance).

Myroslav Irchan and several other Ukrainian intellectuals arrested during the Stalinist purges were posthumously rehabilitated in 1957 as part of Nikita Khrushchev’s official condemnation of the “cult of Stalinism.”

Two monuments were unveiled in his honour – one in his native village and one in Kolomyia.