In August 1910, to draw attention to the issue of equal rights for women, Clara Zetkin came up with the idea to celebrate Women’s Day annually at the beginning of March.

From the time that 100 participants of the Second International Conference of Women-Socialists in Copenhagen had agreed to her proposal, the meaning of this holiday changed repeatedly. Such changes were especially striking in the USSR, a country which proclaimed socialism as its public. Let’s trace how the day of women's solidarity in combatting gender discrimination turned into a holiday of “spring, love and eternal femininity.”

Apart from numerous powerful women’s organizations, the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire was full of active conscious female members of different pro-leftist political movements. Since they treated the issue of women’s equality very seriously, a number of political parties were forced to include this demand into their programs. One should not forget that the February Bourgeois Revolution in Tsarist Russia, which, eventually, led to overthrowing the monarchy and initiated democratic transformations, began with street mass protests of women demanding ”Bread and peace.”

This significant event in Petrograd took place on 23 February 1917 by the Julian calendar. Later, in October 1917, when the Bolsheviks had come to power, they were forced to repay women for their support, and to recognize their contribution to revolutionary events declaring equal political, social, and civic rights for women on the legislative level. Nevertheless, in reality, the Bolsheviks regarded the potential of organized and conscious womankind as an instrument. They aspired to take control of it and use it to strengthen their own political influence on society.

Early Soviet period: absorbtion by the state and propaganda

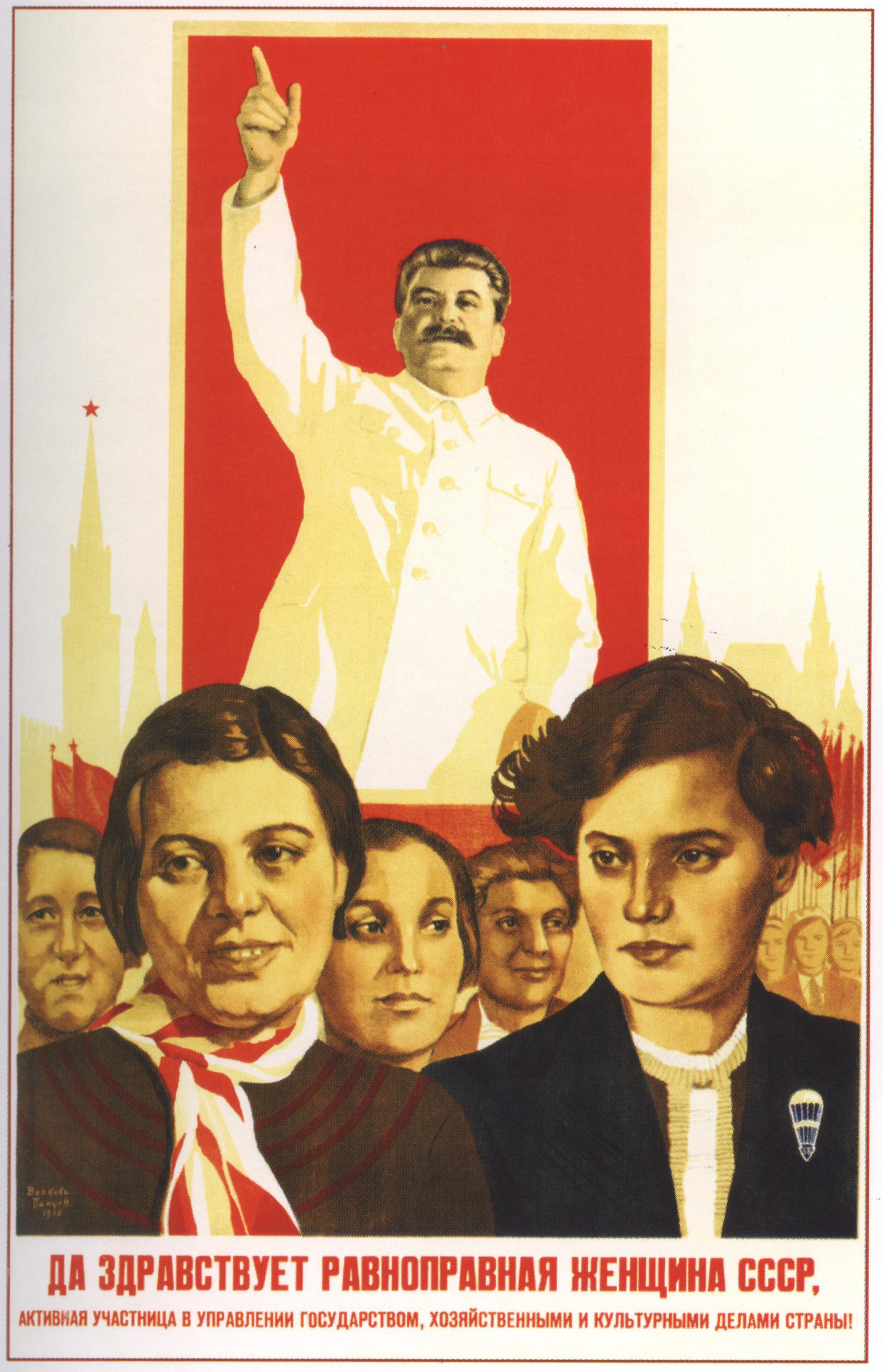

The first step on this way was a decision made in 1921 that gave 8 March status of an official state holiday. But its meaning began being systematically eroded in the very early years of the Soviet rule, first of all, due to the shift of accents from gender equality to class struggle. Political posters of that time named this day as the solidarity day of ”women workers,” ”female proletarians” etc.

Meanwhile, women were actually deprived of any initiative in terms of defining the format and actual possibility of organizing massive events in commemoration of International Women’s Day. These initiatives were passed to women's councils, special structures within the party units that were established back in 1919 to

broaden the involvement of women in support of the Bolshevik policy. True, in the 1920s, celebration of 8 March was still related to equal rights for women. This day was used as an opportunity to point out problems women faced in social, educational, political and other spheres.

Political rhetoric of that time was rich in slogans on "liberation of women from kitchen slavery" and solidarity of workers and peasants in the class struggle against their enslavement. Actually, this corresponded with priorities in gender policy of the first decades of the Soviet rule. Soviet emancipation project aimed at mass mobilization of women for the construction of communism which required their education and training, as well as their broad engagement in the public sphere. It was based on the idea of equalizing women with men through leveling, blurring, and eliminating any differences between sexes.

Propagandistic posters of that time display the male-like image of a proletarian woman lacking traditional feminine traits adverted as ”bourgeois remnants.” The official discourse, presented in the press back then, imposed the idea that the Communist Party and the Soviet government granted women rights, released them from the patriarchal yoke, raised them to a higher level, gave them an opportunity for self-fulfillment, and so on. Hence, women were expected to pay tribute with their selfless work, justifying high expectations and proving that they were worthy of the credit of trust given.

In this period, the public consciousness consolidated the idea that the Soviet state and the Communist Party granted women their rights, instead of women winning or defending them on their own during the revolutionary transformations.

Soon, it became clear that state-sponsored efforts to make the daily chore communal (creation of public cantines, laundries, kindergartens, etc.), as promised within the implementation of grand emancipation plans, failed. So, the state had to adjust its course on female emancipation by stressing women’s roles in establishing socialist life and raising their kids in the communist spirit.

In the 1930s, the commemoration of 8 March became more explicit at the official level. Solemn assemblies of labor collectives and party units took place according to unified scenarios, adopted and introduced from above by the central authorities.

After the new Stalin Constitution of the USSR (1936) had entered into force, and the ”women’s question” had been officially proclaimed resolved, 8 March turned into an occasion to review the best achievements of Soviet women which were assessed on their quantity and quality in special reports by the party leadership. The holiday became increasingly propagandistic, with less and less possibilities to discuss women's issues and be vocal about facts of gender-based discrimination.

At the same time, due to demographic problems that arose in the USSR in the result of mass political repressions and the Holodomor famine of 1932-1933, the country's leadership was forced to take measures to increase the birth rate. The press of that period released more and more publications to emphasize the value of maternity and encourage women to devote more attention to their maternal functions.

The theme of motherhood in the celebrations of 8 March gained a special prominence after the Second World War, which corresponded quite well to the strengthening of the party’s and government’s pro-natalist policy. In view of the demographic crisis caused by the war, in 1944, a number of state incentives was introduced for mothers with many children and single ones. Among such were an honorary title of "Mother Heroine," a medal of "Mother Glory,” or "For Motherhood” which provided for a number of ponderable social benefits and help.

The post-war official rhetoric was fundamentally different from that of two previous decades. Instead of appeals to eliminate the divergence between sexes, it started endorsing those gender differences and emphasizing their social importance.

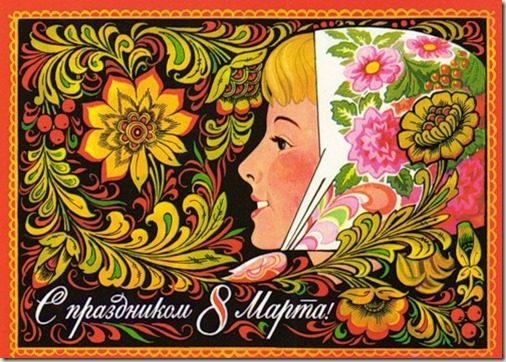

The image of a brave male defender of the fatherland opposed the image of a caring, loving and faithful woman-mother, that were becoming more and more feminine in the visual propaganda of that time. This tendency towards the polarization of gender roles (with typical mutually supportive notions of a "real man" and a "real woman”) dominated gender ideology of the state up until last years of the USSR's existence.

The Cold War period was marked with even more active use of the "free Soviet woman" image in the Soviet propaganda.

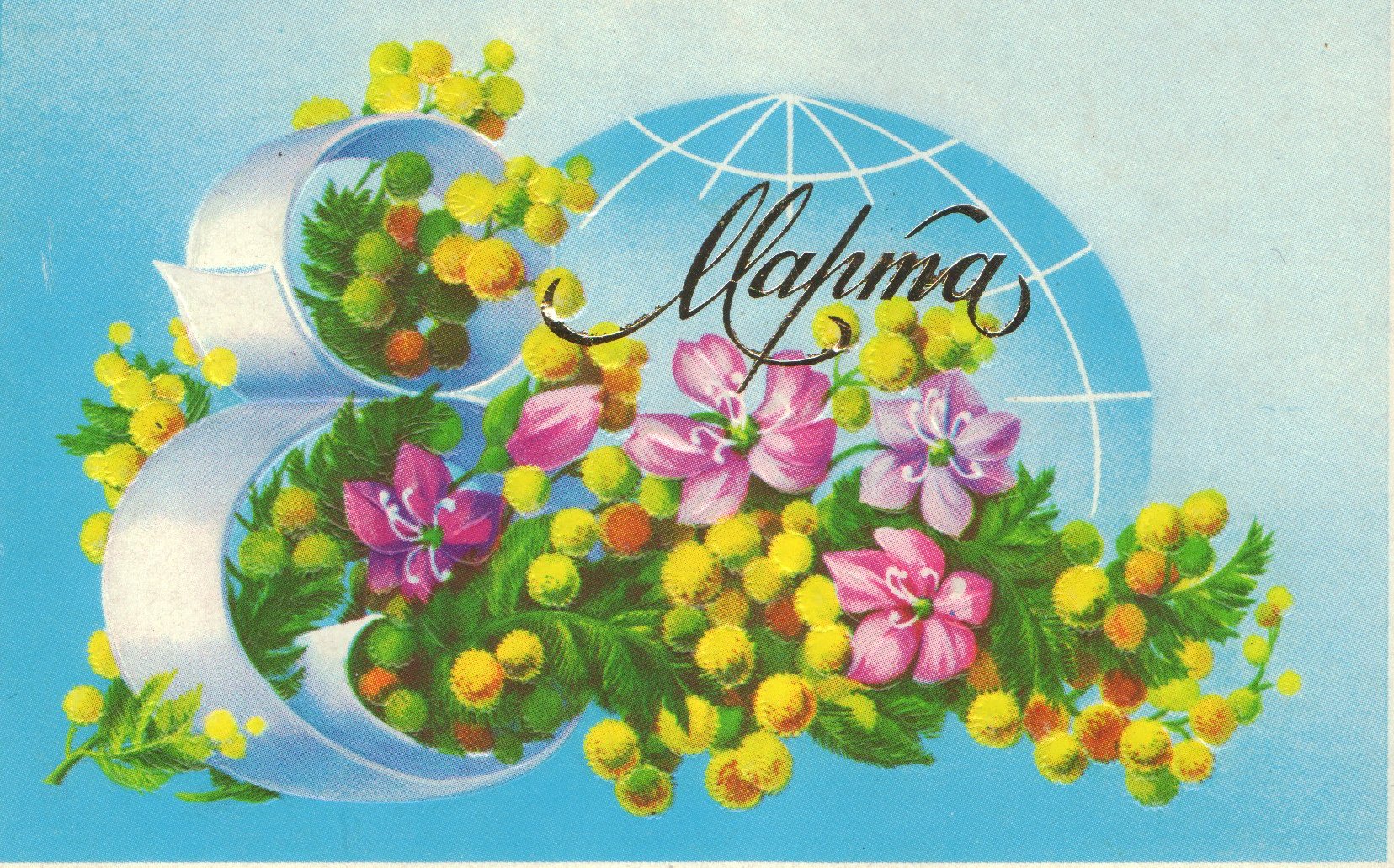

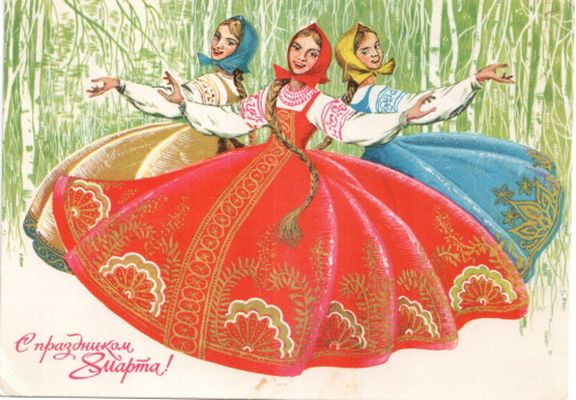

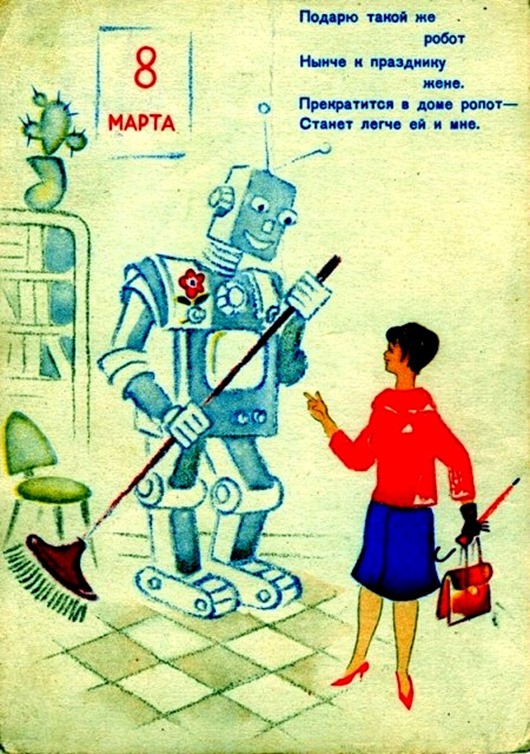

In the early 1960s, greeting postcards and posters on the occasion of 8 March, were abundant in images of smiling women (often with children), representing various races and nationalities of countries from the socialist camp that claimed its solidarity in the struggle for world peace and testified to privileges of the state socialist order.

8 March celebrations happened under the same exalted slogans, such as "Soviet women are the happiest and the most equal women in the world!”, in contrast to the miserable situation of exploited and discriminated women of capitalist states. The commemoration of International Women's Day in labor collectives was accompanied by glorifications of the party and the government for their tireless care for women and by rewarding female shock-workers and winners of socialist competitions for their professional achievements for the benefit of the socialist homeland.

1965, when 8 March officially became a day off, was the turning point in the meaning and style of Women's Day commemoration. In fact, this decision moved such celebrations from the public space into a private, family setting. The period of "Khrushchev's Thaw" brought some liberalization for public life, improvement of welfare, "rehabilitation" of values, once branded as "bourgeois remnants,” and of consumerist practices (such as fashion, cosmetics, interior design, elements of etiquette, etc.). Probably, that is when the tradition to congratulate women on 8 March with flowers, to give them sweets and other pleasant whatnots has been conceived.

In the context of personal congratulations, the official rhetoric about "female worker" was inappropriate, while praising a woman-mother (which at that time had already become the core of the "Soviet super-woman" image) was fully in line with the spirit of the family holiday. So, from the end of the 1960s, one can confidently talk about the transformation of 8 March into a holiday similar to Mother's Day.

If until then, festive 8 March greetings had coincided with those for mothers just sporadically, the 1970s built a stable and unequivocal association between this holiday and maternity. Kindergartens introduced a tradition to organize children's holidays with poetry and songs honoring their beloved caring mothers on the eve of 8 March, and the press abounded in publications about mothers-heroines on those days.

Late Soviet period and final depolitization

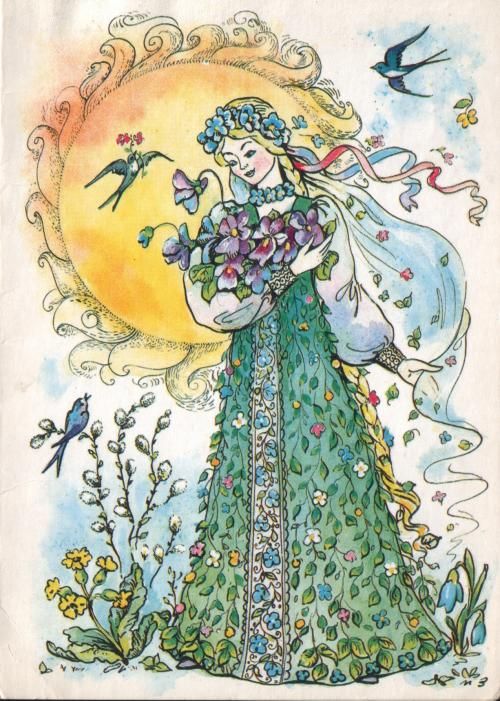

Put into the private family milieu, the holiday was drifting further towards depoliticization of its meaning. Gradually, it turns into a day of honor for all women. At the end of the 1970s, in addition to student practice of congratulating their school teachers, boys started a new fashion of congratulating their girls-classmates. A bouquet of snowdrops and a soft toy became regular attributes of the holiday.

This tendency to "rejuvenate" the heroine of the holiday was followed by complete disappearance of hints on its political meaning. After all, a little girl can not be politically active. Thus, such elements as flowers, sweets, and gifts filled the holiday’s symbolic space.

The ultimate depoliticization of the Women's Day happened not so much at the level of official celebrations, as it did in the private sphere. Although in labor collectives celebrations with typical speeches filled with propagandist cliché's were still a thing, 8 March became a full-fledged family holiday with rituals to gratify women.

At the visual level, a final break from the original political meaning of the Women's Day happened when there were no mentions of women left in the postcards, neither in images nor in texts. Fairy characters and cartoon animals invaded late Soviet postcards, and spring became the main theme for greetings. Spring flowers and landscapes drew an association with the awakening of nature, while links with women were fading each time more, perhaps, with an exception for youth and prosperity of women's beauty.

It is hard to say to how deliberate these trends towards depoliticization of 8 March were, as well as to what extent they were orchestrated from above. Nonetheless, considering the fact that all printed materials in the USSR were subject of political censorship and should have been approved by competent authorities, one may assume that this process was not so spontaneous or arbitrary.

In any case, contrary to original ideas that feminists put in this holiday in the early 20th century, International Women’s Day was filled with meanings, attributes and rituals which framed its celebration in a very specific way in the USSR in the late 1980s.

The stolen holiday was turned against women themselves. In the country, where the "women's question" had been considered solved long ago, one-day-a-year hypocritical exaltation and gifting women happened under circumstances of their ubiquitous exploitation, discrimination, and disregard for women’s numerous needs and problems.

Meanwhile in the world

Meanwhile, in the 1970s, the world was engulfed by the so-called "second wave of feminism” and women’s organizations vigorously pressured their governments and international organizations, demanding to put equal rights and opportunities into practice. These massive and purposeful efforts led to changes in national laws around Europe and North America.

Moreover, in order to draw attention to problems of discrimination against women, the UN proclaimed 1975 as Women’s year, and in 1977, he UN General Assembly approved the resolution No. 32/142 that suggested its member states to annually celebrate International Women’s Day. In 1979, the General Assembly of the United Nations approved the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women which was ratified by 150 countries, including the Ukrainian SSR in 1980. In this way, its state parties not only recognized the existence of discrimination against women, but also committed themselves to take measures and to endeavor to eliminate gender-based inequalities.

Since 1996, under the auspices of the United Nations, International Women's Day is celebrated annually with a certain slogan to emphasize one of the problems women face on their way to equality.

For example, in March 2000, the 8 March topic was "Women unite for peace" and in 2013, the Women's Day celebration happened under the UN motto "A promise is a promise: Time for action to end violence against women." The problem of violence against women is extremely relevant to Ukraine and concerns not only the widespread and shameful practices of domestic violence, but also women’s trafficking, prostitution, sexual harassment, etc. 2019's motto “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change” is also relevant to modern challenges [examples adjusted and edited according to the date of publication].

Yet, for many years, women's organizations in Ukraine have been struggling to stop the hypocritical and humiliating practice of late-Soviet style celebrations of 8 March and restore its authentic political meaning of International Women Solidarity Day that would advocate for their own rights and overcome gender-based discrimination. Still, for many Ukrainians it is not so easy to renounce the rare opportunity of receiving some attention and gifts on this day.

Read more: Women’s Day in Ukraine is seriously in limbo

Read also:

- Ukrainian women at war: from Women’s Sotnya to Invisible Battalion

- Ukraine’s Health Ministry opens up previously banned 450 professions for women

- 20 Prominent Ukrainian Women

- Ukrainian Women at War