In 1972, Vasyl Stus was arrested for anti-Soviet propaganda. As his wife Valentyna Popeliukh recalls the moment:

“Until 3 AM, or even longer, they were going through the books, manuscripts, everything that was in the house, even rags. I was watching them, because it was unbelievable. I never would have thought that they would come to look for something there. What could we hide from them? “

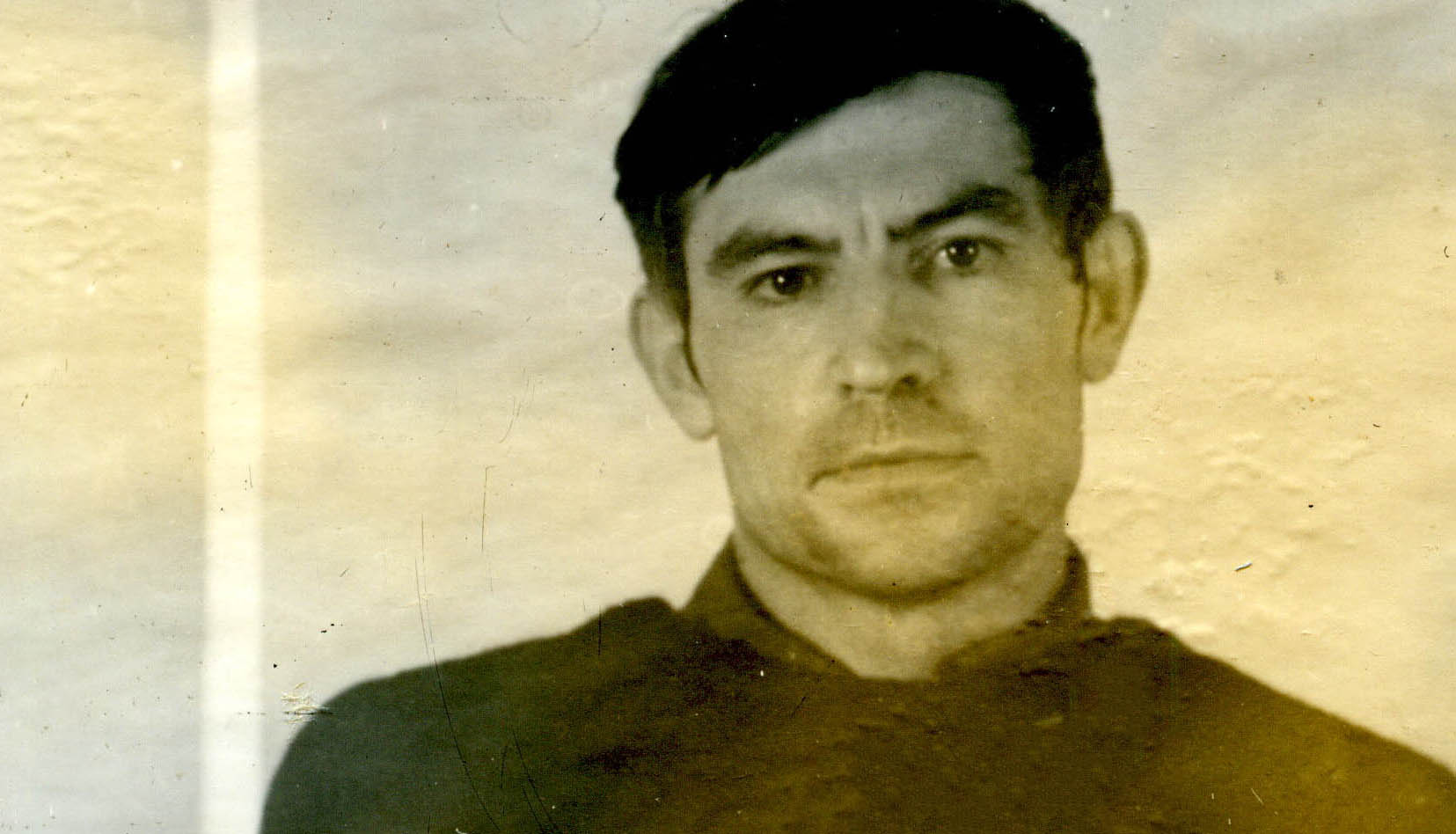

Vasyl Stus served his first sentence in the Mordovian prison camps. After seven years of imprisonment, he returned to Kyiv and joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. In 6 months, he was arrested again, once more for anti-Soviet propaganda.

Dmytro Stus

, the son of Vasyl Stus who is now Director general of Kyiv's Taras Shevchenko Museum, recalls important words his father told him when the Soviet police were taking him away around midnight:

“My son, I understand very well what you went through today: humiliation, despair, weakness. It’s a horrible cocktail for a real man. But I’m begging you, don’t let your eyes turn cold and send hatred into the world. As soon as you allow it, the world will respond to you in the same way. If you cannot forgive these people, try at least to understand them. I cannot do it now, unfortunately.”

Vasyl Stus was sent to a Russian prison where the majority of the men were serving time for murder. Members of the Helsinki Group were kept in separate cells. This is according to Levko Lukyanenko, who was one of them.

From the memories of Levko Lukyanenko, former politican prisoner and co-founder of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group:

“Vasyl and I saw each other in prison when he first arrived. Then, we were taken to the 35th zone on the Vsekhsviatskaya station. They placed us both in one cell. There, we held each other’s hands for the first time, said hello, and hugged. It was a KGB operation and we understood its goal: they wanted to hear what Stus would tell me about Kyiv. On the other hand, they knew that I would tell him about prison. What were we supposed to do? Stay silent and not talk to each other? We decided to talk, but if we wanted to mention last names, we would write them down on paper, burn it, and eat it.”

In August 1985, Stus was sent to solitary confinement for leaning against his bunk and reading a book. In protest, the poet went on a hunger strike. He died at night on September 4th. Levko Lukyanenko recalls:

“On the first day, we didn't know what to make of it. I went to the head and asked him what happened to Vasyl Stus. He asked why I defended him. He shouted at me, and said that he was taken to the hospital. After that, Romashov, a Russian, told us that at night he heard Vasyl scream.”