On 8 June 2017, three days after Montenegro became the 29th NATO member, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a bill setting NATO membership as Ukraine's foreign policy objective. 276 MPs out of the needed 226 voted in favor, 25 were against, and 3 abstained.

Parliament Speaker Andriy Parubiy, one of the authors of the bill, explained before the vote that the document will solidify "Ukraine's main security course - NATO membership."

"Russian aggression against Ukraine, the annexation of a part of Ukrainian territory has set urgent targets before the Ukrainian state to ensure real national security. The experience of a number of countries neighboring Ukraine shows that in the current environment they consider the structures of collective security, which operate on principles of progressive democratic values, the most effective of which is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, as the most effective tool for ensuring security, territorial integrity, and sovereignty. The major expansion of the organization in recent years is a convincing confirmation of this," the bill's memorandum states.

The authors of the bill determined that one the basic principles of Ukraine's foreign policy is to deepen cooperation with NATO with the goal of NATO membership.

The NATO Headquarters has "taken this decision into consideration," according

to Ukrinform, and stressed that Ukraine's main priorities remain reforms and modernization of defense and security institutions to achieve NATO standards.

A long and complicated history of relations with NATO

Ukraine became the first CIS country to enter NATO's Partnership for Peace program in February 1994, and official cooperation began one year later. In 1997, the first official NATO Information and Documentation Center opened in Kyiv and a NATO-Ukraine Commission was established. But in 2002, Ukraine-NATO relations soured as leaked tapes appeared to reveal that Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, apart from ordering to kidnap the Ukrainian journalist Georgiy Gongadze, arranged the transfer of the sophisticated Ukrainian Kolchuga system to Iraq. The scandal unfolded amid a political crisis and protests against Kuchma's authoritarian rule in Ukraine. The Ukraine-NATO Action Plan adopted in 2002, as well as Kuchma's declaration that Ukraine wanted to join NATO, and the sending of Ukrainian troops to Iraq in 2003 could not mend relations.

Nevertheless, in 2003 the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a law "The foundations of national security," in which NATO integration and NATO membership were - much like in today's law - proclaimed a key goal of foreign policy. The initiative didn't live long: as soon as Poland became an EU member state, it appealed to Brussels insisting that the Union offers Ukraine membership prospects, which the European Commission declined with a mere partnership offer. The irritated Kuchma ordered to cross out NATO membership from the list of Ukraine's strategic goals in 2004.

After the Orange Revolution in 2004 in which Kuchma was replaced by Viktor Yushchenko and expectations were high for a pro-EU and pro-NATO course. But internal quibbles and an absence of unilateral support for NATO within Ukraine's population hampered the plans: in 2008, the second Yulia Tymoshenko cabinet's proposal for Ukraine to join NATO's Membership Action Plan was met with internal opposition, and despite US and Polish support at the 2008 Bucharest summit, the Membership Action Plans for Ukraine and Georgia were not approved , having faced opposition by France, Germany, and Italy. However, a declaration was adopted stating that the "future of both countries [Ukraine and Georgia - ed] were connected with the Alliance."

After Viktor Yanukovych came to power in 2010, Ukraine's NATO aspirations were curbed as a bill was passed that excluded the goal of "integration into Euro-Atlantic security and NATO membership" from the country's national security strategy. The law precluded Ukraine's membership of any military bloc but allowed for co-operation with alliances such as NATO.

In December 2014, 10 months after Yanukovych fled following the Euromaidan revolution, after which Russia occupied Crimea and orchestrated a war in eastern Ukraine, Ukraine renounced this non-aligned status. The step was condemned by Russia. President Poroshenko vowed to hold a referendum on joining NATO, and Ukraine signaled it hopes for a major non-NATO ally status within the United States.

Starting from 2015, military exercises took place between NATO members and Ukraine, including Operation Fearless Guardian, Exercise Sea Breeze, Saber Guardian/Rapid Trident, and Safe Skies. In September 2015, NATO launched five trust funds for €5.4 million for the Ukrainian army. In March 2016, President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker stated that it would take at least 20-25 years for Ukraine to join the EU and NATO.

Public support for NATO membership

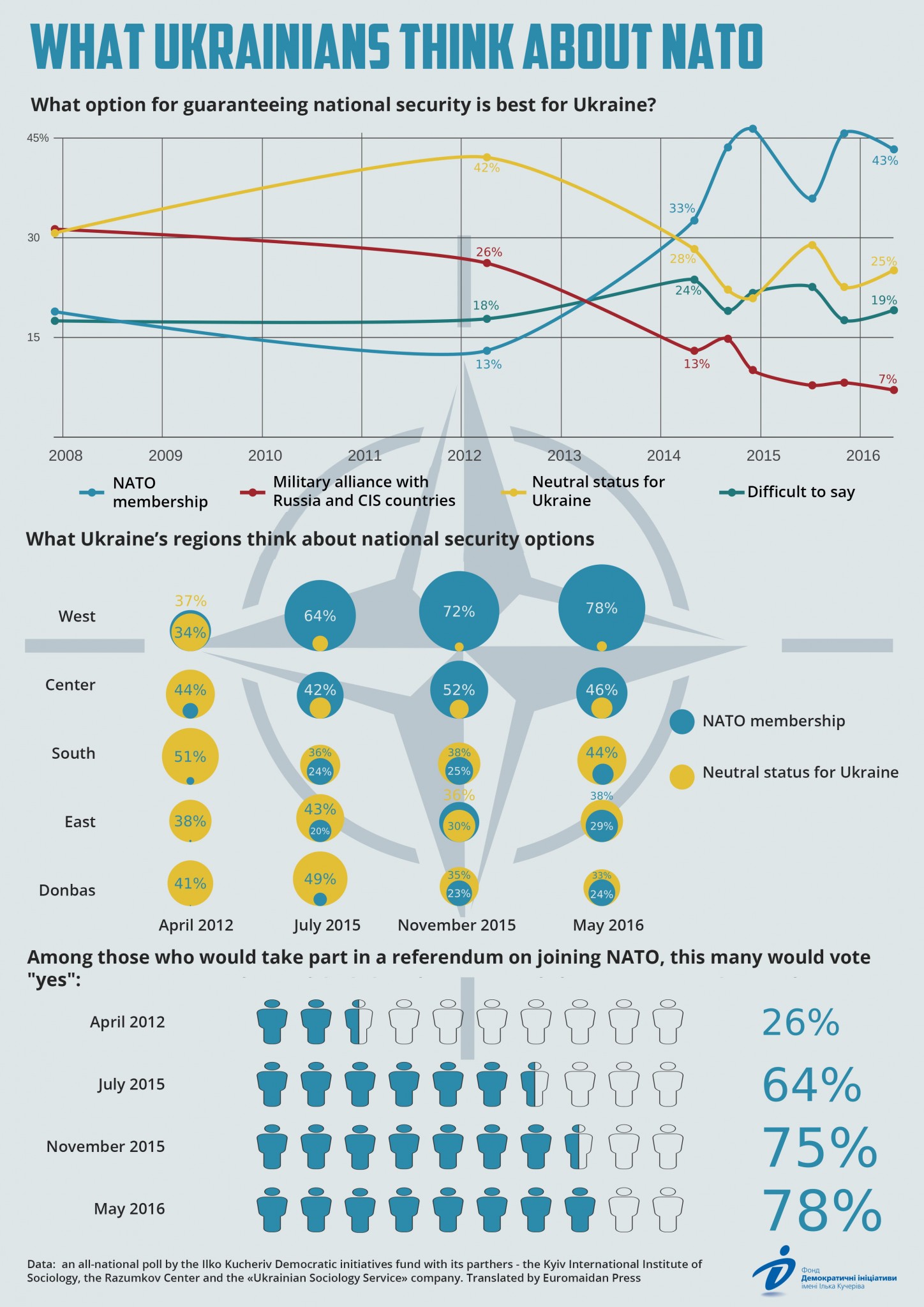

The support of Ukrainians for joining NATO soared following Russian aggression against the country which started after Euromaidan. According to polls by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund, until February 2014, it hovered around 15% and most Ukrainians were in favor of a non-aligned status for Ukraine, after which it soared to 33% and is now at its historic maximum, and support for a military alliance with Russia is at a historic low. Ukraine's NATO membership has the most supporters in Ukraine's western regions, while the South, East, and Donbas are more in favor of a neutral status. If a referendum on joining NATO would be held, 78% of those who would vote would choose "yes."

Below is a graphic by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund, translated by Euromaidan Press.

The most recent poll, released on 28 December 2016 (not shown on graphic), revealed that 71% would vote in favor of joining NATO at a referendum out of the 62% who would participate, and 23% would be against. 44% considered NATO the best option for guaranteeing Ukraine's national security, while 26% hoped for a neutral status and 6% supported a military alliance with Russia.

Russian opposition

Russia's press secretary Dmitry Peskov has already responded to Ukraine's decision towards NATO integration, stating that Moscow traditionally views NATO expansion towards Russian borders with distrust and concern. "We believe that this threatens our safety and the balance of power in the Eurasian region. Of course, the Russian side takes all necessary measures to counterbalance the situation and protect its own interests and safety," he said.

In the past, Russia has spoken out strongly against Ukraine's potential NATO membership. In 2008 then Russian President Vladimir Putin said that Russia may target its missiles at Ukraine if its neighbor joins NATO and accepts the deployment of a US missile defense shield. Prime Minister Vladimir Putin reportedly declared at a NATO-Russia summit in 2008 that if Ukraine joined NATO Russia could annex the Ukrainian East and Crimea.

In an interview with BBC in November 2014, Peskov demanded a "100% guarantee nobody would think about Ukraine joining NATO," an appeal which was rejected two days later by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg as such which would violate Ukrainian sovereignty.

[hr]Read more:

- Is Neutrality a Solution for Ukraine? | Infographic

- Austrian neutrality is no model for Ukraine

- The myth of the "Finlandization" of Ukraine

- That time when the Soviet Union tried to join NATO in 1954

- "Russophiles" aim to steer Bulgaria away from NATO

- Stages of Russian occupation in a nutshell

- NATO losing war of narratives while Russia emerges as leader of nationalist bloc