How does the world look from inside a pro-Kremlin disinformation outlet? We rarely get the opportunity to hear from the people who work in such organisations. So it is something of a scoop every time a whistle blower surfaces and offers a testimony.

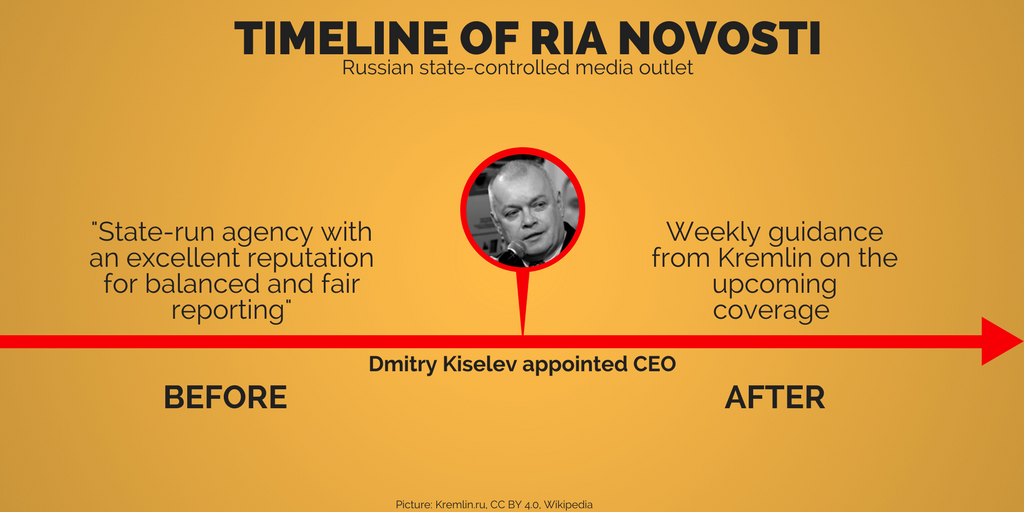

Last week, Coda Story presented a valuable piece of documentation with the article “Confessions of a (Former) State TV Reporter“. It featured Ilya Kizirov, who now works as a reporter for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Russian-language service, but who previously worked in Russian state-controlled media outlet RIA Novosti. According to Kizirov, RIA Novosti was “for years one of the most unusual media organizations in Russia: a state-run agency with an excellent reputation for balanced and fair reporting”. But this professionalism was challenged when Dmitry Kiselev was appointed CEO and, as also reported by other media, announced to his staff that “the period of impartial journalism is over. Objectivity is a myth that we have been offered; it has been imposed on us”. Top-editors told the staff that “there is no more time for truth-seeking”, and that “our country is back in the Cold War era.”

Kizirov’s testimony provides a series of concrete examples of the ways in which the state media are under direct political control. His observations echo what we have described as the Kremlin’s guidelines-based approach

when he recalls how instructions trickled down from the top in the Kremlin to the newsrooms: “Once a week”, Kizirov tells, “usually on Fridays, all key editors of all the government media-platforms would gather at the Kremlin for an ‘editorial meeting.’ These were mostly led by President Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov. A few hours later, a real editorial meeting would take place in the newsroom and, based on the Kremlin meeting, a team of top producers would discuss the upcoming coverage — what issues it would raise and what guests would appear on the evening talk-show”.

The journalist says that key to making educated and experienced journalists work in strict accordance with political guidelines is the social aspect: “Some of these people joined the channel in the early 2000s, when you could speak out on TV and have meaningful debates. Slowly, over the years, compromises, one by one, crept into their lives. By early 2010, these editors and reporters had kids and mortgages and quitting wasn’t an option. The Kremlin’s disinformation campaign depends on such journalists.”

Mr Kizirov tells of a colleague whom he names “Alexei,” and who lost his scepticism on a reporting trip in the Donbas, This has paved “Alexei’s” way to an impressive career in the world of pro-Kremlin media. However, “Alexei” has also, as Kizirov explains, “moved his wife and two young daughters to Vietnam, where they live in a cottage by the beach. In a year or two he hopes to join them there, open a small hotel and ‘forget all the things [he is] covering now'”.

It’s important to stress that Kizirov’s testimony does not stand alone. As we have reported earlier, a series of people have told stories from inside the infamous pro-Kremlin “troll factories”, sometimes as whistle blowers, but also as reporters who have worked under cover. Similarly, foreign journalists who have accepted job offers from Russia Today (RT) have left the organisation and spoken publicly about what it’s like to work as a professional disinformer, some even quitting their positions live on air.