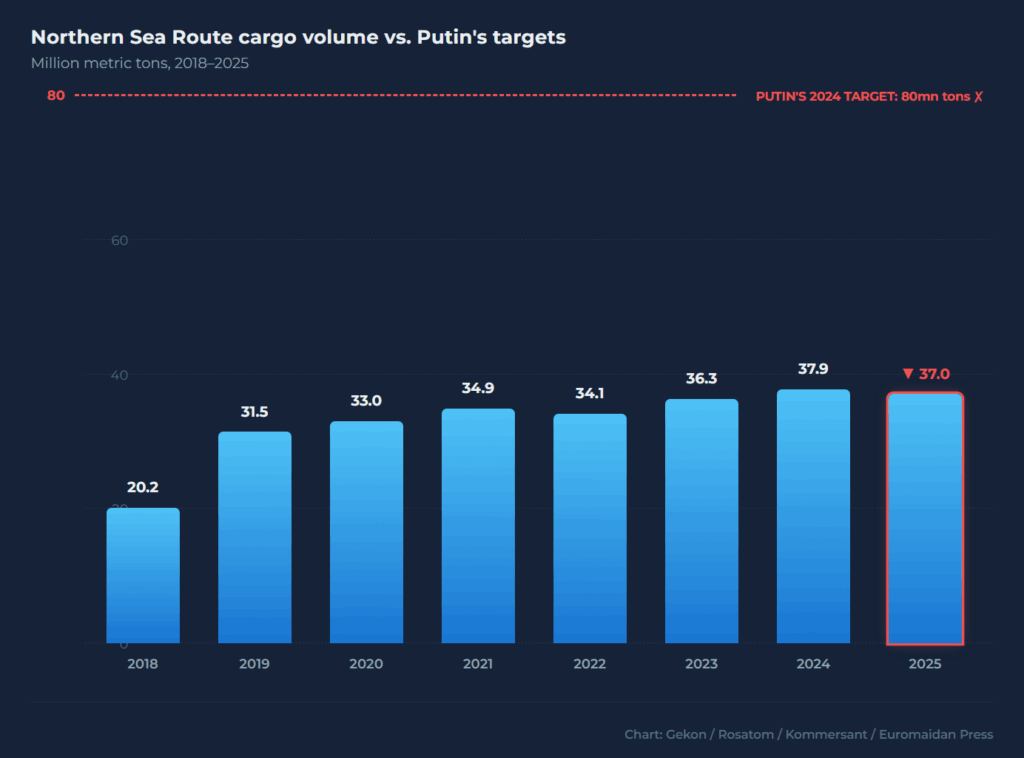

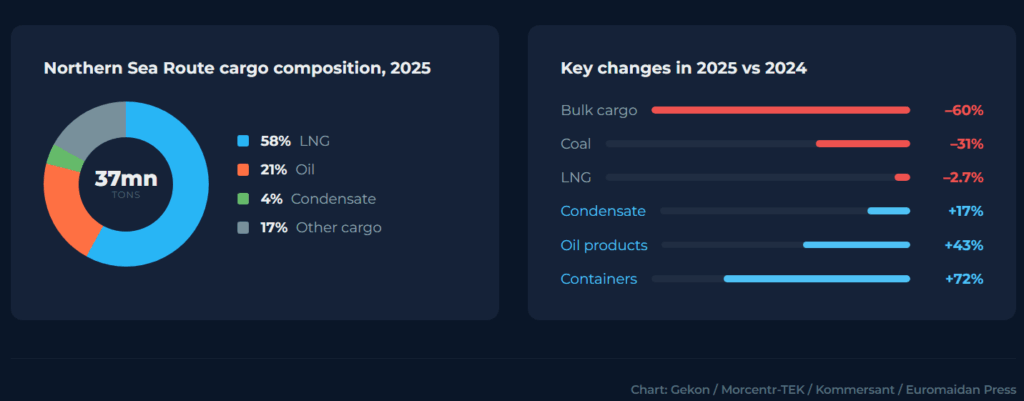

Cargo on Russia’s Northern Sea Route fell for the first time since 2022, dropping 2.3% to 37 million tons in 2025, according to an analysis by Russian consultancy Gekon published by business daily Kommersant on 9 February. The analyst behind the study sees no sources of growth for 2026.

Russia’s northern shipping lane carries the oil and liquefied natural gas that help bankroll Moscow’s war in Ukraine.

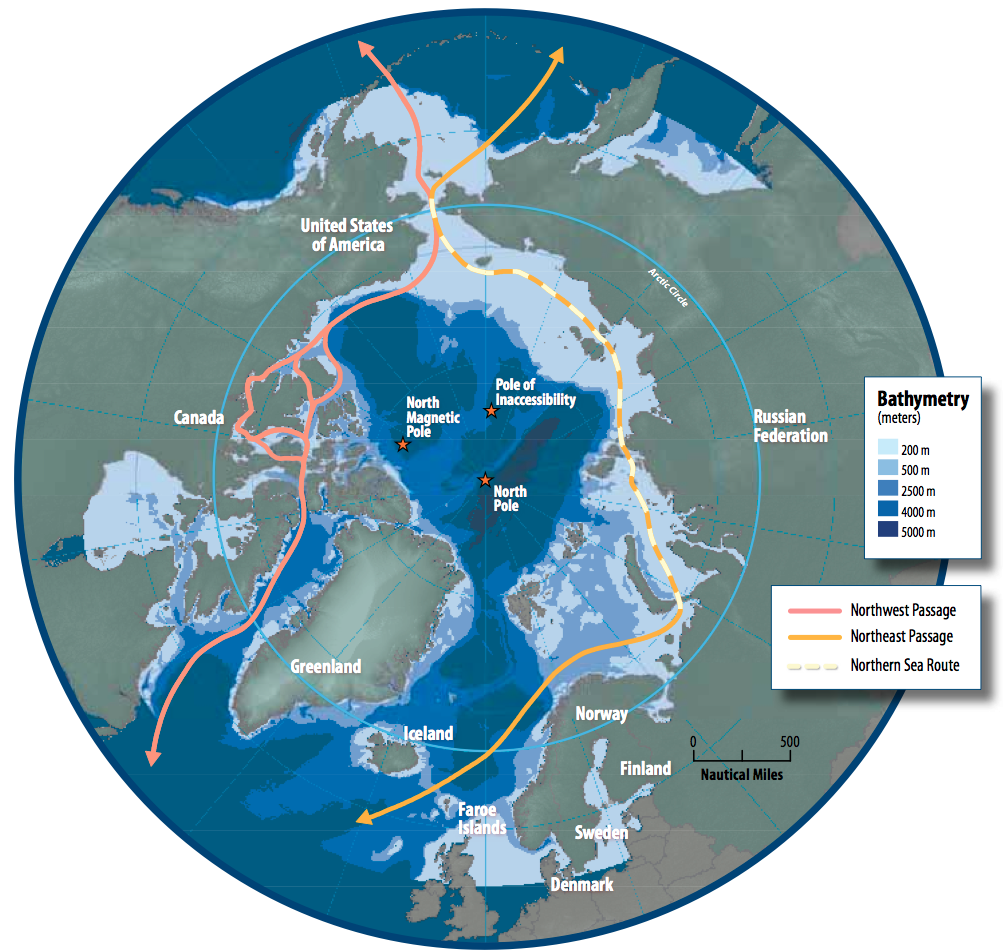

The decline matters beyond the Arctic. Russia’s northern shipping lane carries the oil and liquefied natural gas that help bankroll Moscow’s war in Ukraine—hydrocarbons make up 83% of the route’s cargo. In 2018, Putin signed a decree ordering 80 million metric tons on this route by 2024. Russia delivered less than half, and the number is now going backwards.

The Arctic is melting, Ukraine is bleeding, and G7 “climate leaders” still won’t quit Yamal LNG

The fields are running dry

Shipments of liquefied natural gas—the route’s single largest cargo—fell 2.7% because of scheduled repairs at Novatek’s Yamal plant, according to Kommersant. Oil from Gazprom Neft’s Novoportovskoye field continued what Gekon head Mikhail Grigoryev called a “smooth decline” driven by the field simply running out. Bulk cargo collapsed by more than 60%. Coal shipments through Murmansk dropped 29%.

In December, a tanker failed to reach the terminal even with two nuclear icebreakers clearing the way.

And both projects meant to reverse the trend are stuck. Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2, hit by Western sanctions and unable to find enough ice-capable tankers, has struggled to ramp up production. In December, a tanker failed to reach the terminal even with two nuclear icebreakers clearing the way.

Rosneft’s Vostok Oil—over $100 billion and the largest oil development on Earth in two decades—has been delayed to 2026. Its 770 km pipeline was less than half complete by the end of 2024. The project’s operator, RN-Vankor, fell under US sanctions in January 2025.

Eight icebreakers, not enough cargo

Russia built the infrastructure for an Arctic superpower. It operates the world’s only fleet of nuclear icebreakers—eight vessels, four of them new. It spent $29 billion on a Northern Sea Route development plan in 2022. Putin ordered 80 million tons by 2024; Rosatom later promised 270 million by 2035—the result: 37 million tons and falling. The icebreakers exist. The cargo doesn’t.

Trending Now

“In 2026 we hope for higher figures, but it’s too early to speak of concrete plans.”

A few categories grew. Oil product shipments rose 43%, container tonnage jumped 72% during the summer shipping season, and Murmansk port sent two large bulk carriers of iron ore to China—330,000 tons total, according to Kommersant.

“In 2026 we hope for higher figures, but it’s too early to speak of concrete plans,” port commercial director Vladislav Yakovchuk told the newspaper. But these gains are marginal. Container traffic moved 321,000 tons for the entire year—less than the Suez Canal handles in a single day.

Even in 2024, when Houthi attacks cut Suez traffic by half, the canal still moved 1.25 million tons of cargo daily, according to the Canal Authority’s annual report.

A pattern seen before

The Northern Sea Route peaked at 6.58 million tons in 1987 under the Soviet Union, then collapsed to near zero in the 1990s. Its revival after 2012 was driven almost entirely by one project—Yamal LNG—not by any broader breakthrough in Arctic shipping.

“The export orientation of the Trans-Arctic Transport Corridor requires cooperation in Arctic shipbuilding and the formation of new sustainable markets.”

Now the cycle is repeating at larger scale and higher cost. Western sanctions have cut Russia off from shipbuilding technology and LNG equipment. The Rossiya, a next-generation icebreaker meant to enable year-round Arctic navigation, is only 30% complete after years of delays.

And China—Russia’s main remaining buyer—is exploiting Moscow’s desperation, paying 30-40% below market rates for sanctioned Arctic gas.

“The export orientation of the Trans-Arctic Transport Corridor requires cooperation in Arctic shipbuilding and the formation of new sustainable markets,” Grigoryev told Kommersant. In other words: Russia cannot do this alone, and the partners it needs are either sanctioning it or buying at a discount.