Ukraine has banned cultivation of genetically modified crops and begun overhauling its agricultural regulations to align with EU production standards, First Deputy Agriculture Minister Taras Vysotskyi told RBC-Ukraine on 4 February.

In 2028, the EU will review Ukraine’s trade quotas based on the progress the country has made in harmonization.

In 2028, the EU will review Ukraine’s trade quotas based on the progress the country has made in harmonization. Better compliance means better market access. Failure means Ukrainian farmers keep competing against EU producers who receive government subsidies covering a third to half of their costs—while getting none themselves.

Going GMO-free in a GMO-dominated world

No genetically modified crops are registered or permitted for cultivation in Ukraine. Legislation fully implementing EU GMO standards enters into force in September 2026, permanently banning GMO corn and temporarily prohibiting GMO sugar beets and rapeseed.

“Ukraine has already adopted the European regulatory model for GMOs and is moving toward GMO-free country status,” Vysotskyi said. “For EU exports, only non-GMO products are used.”

Ukraine is siding with Europe—and betting that non-GMO certification will give it an edge in markets where traceability matters.

The move puts Ukraine on one side of a sharpening global split. The US, Brazil, and Argentina together account for over 76% of the world’s genetically modified crop area. Over 90% of US corn and soybeans are genetically engineered varieties. The EU, by contrast, does not grow GM crops but still imports large amounts for animal feed.

Ukraine is siding with Europe—and betting that non-GMO certification will give it an edge in markets where traceability matters. Ukrainian farmers broadly support the shift, Vysotskyi said, though he noted that some EU member states still permit certain GMO varieties for feed production—rules that could eventually extend to Ukraine.

The pesticide problem no one can rush

The hardest part of EU harmonization isn’t GMOs—it’s pesticides. Switching to EU-approved crop protection products requires replacing equipment, retraining staff, recalculating whether entire crops remain profitable, and physically waiting out five-to-seven-year crop rotation cycles.

“A transition to different pesticides means changing technologies: you need to adapt or replace equipment, retrain staff, revise production plans, and the entire financial model,” Vysotskyi said. “This directly affects costs and forces you to recalculate whether a crop is still viable, or needs to be replaced entirely.”

EU-aligned requirements for livestock housing, ventilation, lighting, and slaughter took effect in January 2026.

Ukraine is asking for at least ten years. And there’s a bottleneck most outsiders wouldn’t think of: European pesticide manufacturers plan production years in advance for existing customers. If Ukraine switches all at once, enough EU-approved pesticides simply won’t exist to meet demand at the scale of Ukraine’s 24.5 million hectares—a shortage that could shut down planting entirely.

Animal welfare is further along. EU-aligned requirements for livestock housing, ventilation, lighting, and slaughter took effect in January 2026. Many producers had been preparing since Ukraine signed its Association Agreement with the EU over a decade ago, and the government has launched training programs to ease the transition.

Four years without subsidies

Ukrainian farmers have operated through the entire war without the systematic subsidies their EU competitors rely on. European producers receive an average of €250-300 ($295-354) per hectare in government support. Applied to Ukraine’s farmland, that amounts to roughly €7 billion ($8.3 billion)—money Ukrainian producers have never seen.

“Ukrainian producers work without systemic subsidies, so they focus on maximizing profitability per hectare rather than maximizing physical output,” Vysotskyi said. That explains why Ukrainian crop yields run about 14% below EU averages—not a technology gap, but an economic choice by farmers who can’t afford to grow more than they can sell at a margin.

Trending Now

“Either we systematically complete this path, or we lose the opportunity to further expand access to the EU market.”

This may change. On 3 November 2025, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed into law the creation of a Payment Agency—the institution through which EU Common Agricultural Policy subsidies are channeled.

The government designated Ukrderzhfond to fill this role in late December, and it must be accredited and operational by 2027—in time for the EU’s next multi-year budget cycle starting in 2028.

“Either we systematically complete this path, or we lose the opportunity to further expand access to the EU market,” Vysotskyi said. “There is no other strategy.”

Competing against Russia in global markets

On global markets, Russia remains Ukraine’s main agricultural rival, particularly in wheat. But the competition isn’t purely economic.

“Russians compete not only on cost, but by somehow influencing governments, offering them something—the state gets involved in the terms of delivery and trade,” Vysotskyi said, declining to name specific countries.

Ukraine exported $22.6 billion in agricultural products in 2025—about 56% of all Ukrainian exports. Of that, $10.7 billion went to the EU, and the rest was split between the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The EU’s share fell from 52.1% to 47.5% after quotas replaced the wartime trade liberalization, though total EU-bound exports still exceed pre-war levels by roughly $3 billion.

By 2028, Kyiv expects to have completed enough of the transition to negotiate better terms.

Russian shelling of port infrastructure periodically cuts monthly export volumes by 20-30%, but over 90% of Ukraine’s agricultural shipments still move through the Black Sea corridor, which Ukraine secured after its naval drones expelled Russia’s Black Sea Fleet from Crimea.

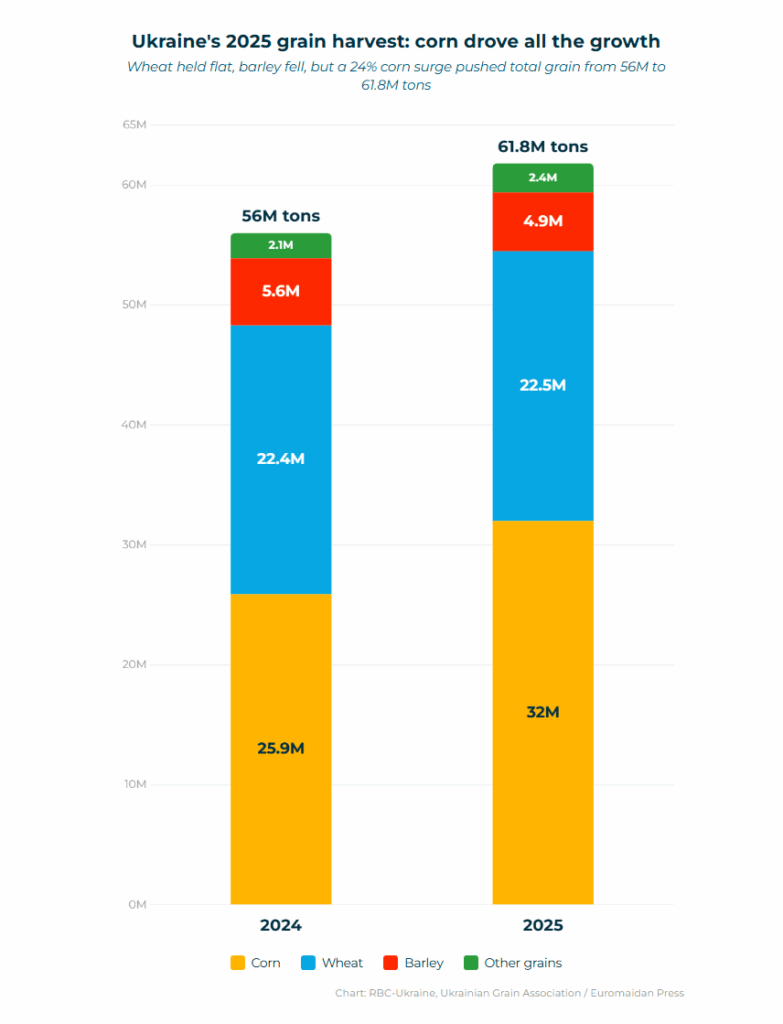

The country harvested 61.8 million tons of grain in 2025—up from 56 million the year before—and over 80 million tons of grain and oilseed crops combined, driven largely by expanded corn planting as cheaper Black Sea logistics made exports viable again. By 2028, Kyiv expects to have completed enough of the transition to negotiate better terms.

Ukrainian farmers, meanwhile, keep planting.