Russian President Vladimir Putin acknowledged that Russia’s GDP grew only 1% in 2025—a collapse from 4.3% the previous year—while claiming the slowdown was intentionally “man-made” to curb inflation. The admission came the same week a Kremlin-linked think tank declared that Russia has formally entered a systemic banking crisis.

The trajectory

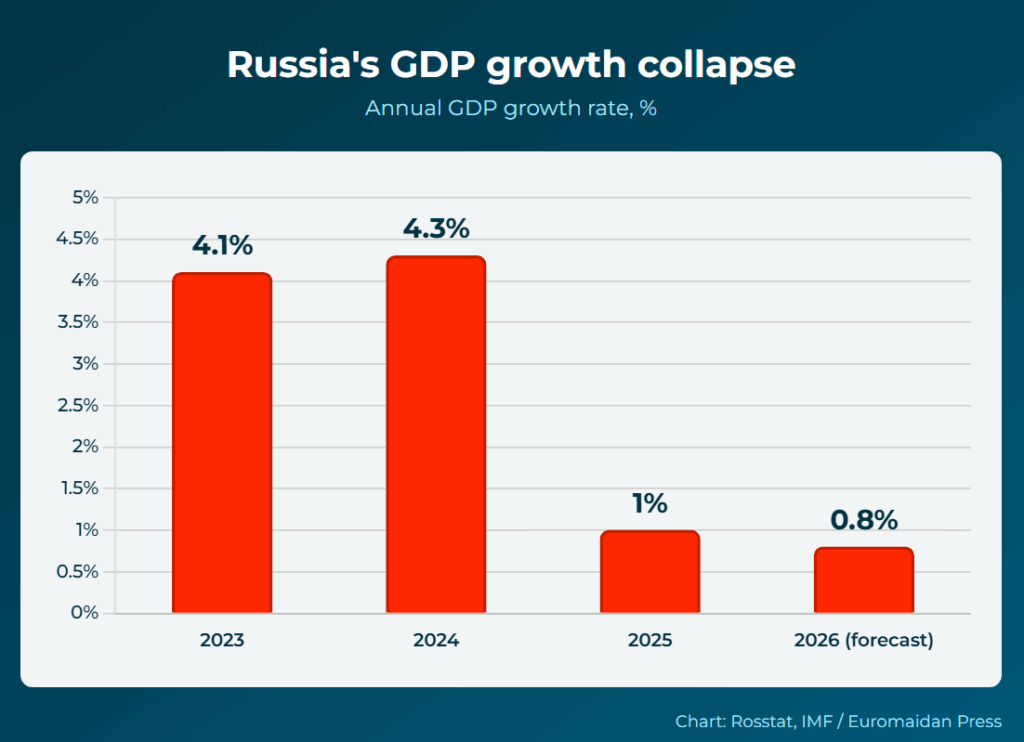

The growth numbers trace a clear arc:

- 2023: 4.1%

- 2024: 4.3%

- 2025: 1% (Putin’s admission)

- 2026: 0.8% (IMF forecast)

The IMF projection would place Russia at the bottom of major economies—below war-torn Ukraine’s projected 2% growth. Western sanctions, dismissed by Moscow for three years, appear to be biting harder than the Kremlin admits.

Banking crisis is here

The Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMACP), a Moscow-based institute with ties to government economic planning, stated in its January 2026 report that Russia’s banking system now meets formal criteria for systemic crisis. Problem assets exceed 10% of total bank holdings—the threshold that defines a crisis under the IMF’s international standards.

Small and medium business loans are hit the hardest, with 19% classified as problematic. The report warns of “high risk” of depositor flight if conditions worsen and rates the probability of recession—defined as negative GDP growth—by July 2026 as “high.”

The spin: “man-made” slowdown

Putin framed the growth collapse as deliberate policy, according to the Institute for the Study of War. He claimed inflation had fallen to 5.6% by December 2025 and that January’s uptick to 6.4% was expected following Russia’s VAT hike from 20% to 22% on 1 January.

In Volgograd Oblast—historically one of Russia’s agricultural heartlands—the numbers are even worse.

But food prices tell a different story. Bread prices rose 14.6%—one and a half times faster than official overall inflation, according to The Moscow Times. Rye prices jumped 25%, rye bread 15%.

In Volgograd Oblast—historically one of Russia’s agricultural heartlands—the numbers are even worse. Cucumber prices jumped 37.9% in the first two weeks of January alone, tomatoes rose 25.1%, and potatoes climbed 11.2%, regional statistics office Volgogradstat reported. Meat followed: lamb up 2.2%, pork 2.0%, beef 1.8%.

Russian newspapers reported “galloping inflation” at the start of 2026, BBC correspondent Steve Rosenberg noted from Moscow, with publications linking rising prices to the VAT hike enacted to finance the war.

“A systemic problem”

The tax changes are crushing small businesses. In Pskov, a 190,000-inhabitant oblast center at the Estonian border in northwestern Russia, the city’s oldest pizzeria, “Moya Italiya,” shut its dining room on 1 January after the new tax regime became “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Pskovskaya Lenta Novostei reported. The restaurant now operates delivery-only from what the report called a “deeply hidden underground kitchen.”

Business owners increasingly ask customers for cash payments to avoid bank fees and taxes.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov was forced to acknowledge the damage. A bakery called “Mashenka” in Moscow Oblast had appealed directly to Putin during his annual “Direct Line” broadcast, warning it would have to close due to the new taxes. When asked about the case, Peskov admitted: “There is a systemic problem that was not taken into account when the corresponding changes were developed.”

Business owners increasingly ask customers for cash payments to avoid bank fees and taxes, the Pskov newspaper noted—a return to shadow economy practices Russians thought they had left behind.

Industry trapped

Trending Now

Beyond banking, Russia’s productive capacity is eroding. The director of NPN Holding, a manufacturing company, told Pskov regional radio that reviving Russian industry is now impossible: “No market, no credits, no ability to buy high-tech equipment.”

“Even China, known for its industrial achievements, does not sell us metalworking equipment,” he said. “It’s all because of sanctions.”

A State Duma deputy acknowledged at parliamentary hearings that Russia’s light industry remains 60-80% dependent on imports—a vulnerability the war has only deepened.

Investment paralysis

Senior officials are now acknowledging what the numbers show. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak admitted to Russian senators on 3 February that investment in the economy has flatlined.

“Investment growth for nine months of 2025 was 0.5%. For the year, it will most likely be zero or slightly above,” Novak said.

For 2026, the ministry now expects a further 0.5% decline.

In September 2025, the Economy Ministry had forecast 1.7% investment growth. Instead, Rosstat recorded the first year-on-year investment decline in five years—down 3.1% in the third quarter. For 2026, the ministry now expects a further 0.5% decline.

Transport, construction, coal mining, and oil and gas sectors led the collapse, crushed by the Central Bank’s high interest rates. Only the military-industrial sectors continued growing. In Novosibirsk, a small-arms ammunition factory reported boosting output by 60% under a federal productivity program—a stark contrast to the civilian economy’s paralysis.

The electronics industry shows what happens when state support falters: it had been expanding investment until the government cut subsidies in Q3 to balance the budget. “As soon as the state reduces financing, investments shrink,” The Moscow Times noted.

Budget trapped by the ruble

Russia’s 2026 budget faces a structural vulnerability beyond falling oil prices, former Ukrainian Infrastructure Minister Volodymyr Omelyan noted on 4 February. The budget depends not on the dollar price of oil but on the ruble price per barrel—and the ruble’s recent strengthening works against Kremlin revenues.

The ruble strengthened 25% over the past year, which sounds like good news—but for oil, gas, and metals companies that earn in dollars and pay costs in rubles, it means shrinking profits.

As Omelyan points out, Moscow budgeted Urals crude at $59 per barrel, equivalent to roughly 5,400 rubles. But if prices fall toward $50, Russia loses approximately 1,000 rubles on every barrel sold—a potential shortfall of 0.5-0.7% of GDP.

The CMACP report identified the same squeeze from another angle: the ruble strengthened 25% over the past year, which sounds like good news—but for oil, gas, and metals companies that earn in dollars and pay costs in rubles, it means shrinking profits and mounting debts.

Reserves draining

Russia’s National Wealth Fund held $53.4 billion in liquid assets as of December 2025, down from $185 billion in 2021. That’s less than Moscow’s projected budget deficit for 2025 alone. China refused Moscow’s request for macroeconomic support.

Ukrainian economist Volodymyr Vlasiuk told Euromaidan Press in October 2025 that Russia had 12-18 months of war funding remaining. Four months into that window, Putin’s admission suggests the clock is running as predicted.