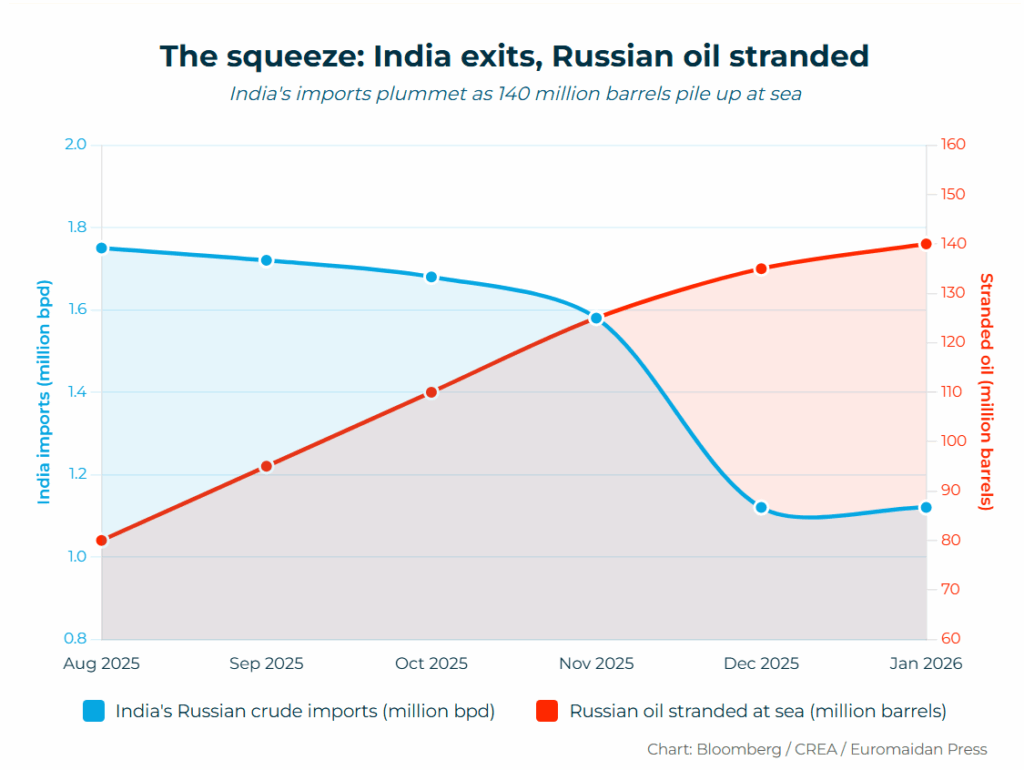

Russia has accumulated approximately 140 million barrels of crude oil on tankers at sea—roughly $3 billion worth—with about 60 million barrels added since late August alone, according to Bloomberg vessel-tracking data. The buildup coincides with a dramatic pullback by Indian refiners, whose imports of Russian crude fell to 1.12 million barrels per day in January—the lowest in over three years.

India and the European Union signed what European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called “the mother of all deals”.

The timing wasn’t coincidental. For three years, Indian refiners gorged on discounted Russian crude while quietly negotiating with Brussels. Then, days after the EU’s ban on refined products made from Russian oil took effect on 21 January, India and the European Union signed what European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called “the mother of all deals”—a free trade agreement representing “25% of the global GDP and one-third of global trade,” in the words of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The loophole closes

The EU’s 18th sanctions package, announced in July 2025, targeted a glaring gap: Indian and Turkish refineries were importing Russian crude at steep discounts, refining it into diesel and jet fuel, and selling it to Europe—effectively laundering Moscow’s oil. The ban, which took effect 21 January, now requires importers to prove their products weren’t made from Russian crude.

India’s Russian crude imports fell 29% in December to their lowest level since the G7 price cap was imposed three years earlier.

Indian refiners saw it coming. Major refineries had already “self-sanctioned,” as Kpler analyst Sumit Ritolia told RFE/RL, announcing they would buy no more Russian crude. India’s Russian crude imports fell 29% in December to their lowest level since the G7 price cap was imposed three years earlier, according to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Bloomberg tracking data shows January imports averaging just 1.12 million barrels per day. Six days later, India and the EU signed their trade deal.

Enforcement pressure mounts

On 23 January, the French navy intercepted the tanker Grinch in the Mediterranean—a vessel suspected of flying a false Comoros flag after departing Russia’s Arctic port of Murmansk. Within hours, two other tankers hauling Russian oil from Murmansk—the Huihai Pacific and the Adonia—made U-turns and headed back to port. President Macron called the seizure a message, as the shadow fleet continues to “finance Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine”.

France seizes shadow fleet tankers; Spain escorts them to a safe harbor.

But the same week exposed the enforcement gap. The tanker Chariot Tide—under EU sanctions since November 2024 for what the bloc called “irregular and high-risk shipping practices”—suffered an engine failure in international waters south of Spain.

Rather than seize it, Spanish authorities escorted the tanker to Morocco’s Tanger Med port. Spain’s Merchant Marine did not explain why. France seizes shadow fleet tankers; Spain escorts them to a safe harbor.

Morocco: the new weak link?

The Chariot Tide’s destination wasn’t random. Morocco has quietly become an established node in the shadow fleet network. Ukrainian intelligence records show multiple sanctioned vessels calling at Moroccan ports—Tanger Med, Mohammedia, El Jorf Lasfar—as part of their regular routes between Russian terminals and Asian buyers.

As enforcement tightens in European waters, will Morocco become the shadow fleet’s Mediterranean safe harbor?

The pattern predates the Chariot Tide incident. In June 2024, Bloomberg tracked several Russian tankers to a bay near Nador in eastern Morocco after Greece’s navy began holding exercises to deter ship-to-ship transfers in the Laconian Gulf. Five tankers were identified anchored there, transferring sanctioned Urals crude to larger vessels bound for India and China, just outside Spanish territorial waters near the enclave of Melilla.

Trending Now

Morocco maintains warm relations with Moscow, signing a fisheries deal in October 2025, allowing Russian vessels in Moroccan Atlantic waters. The question now: as enforcement tightens in European waters, will Morocco become the shadow fleet’s Mediterranean safe harbor?

Environmental time bomb

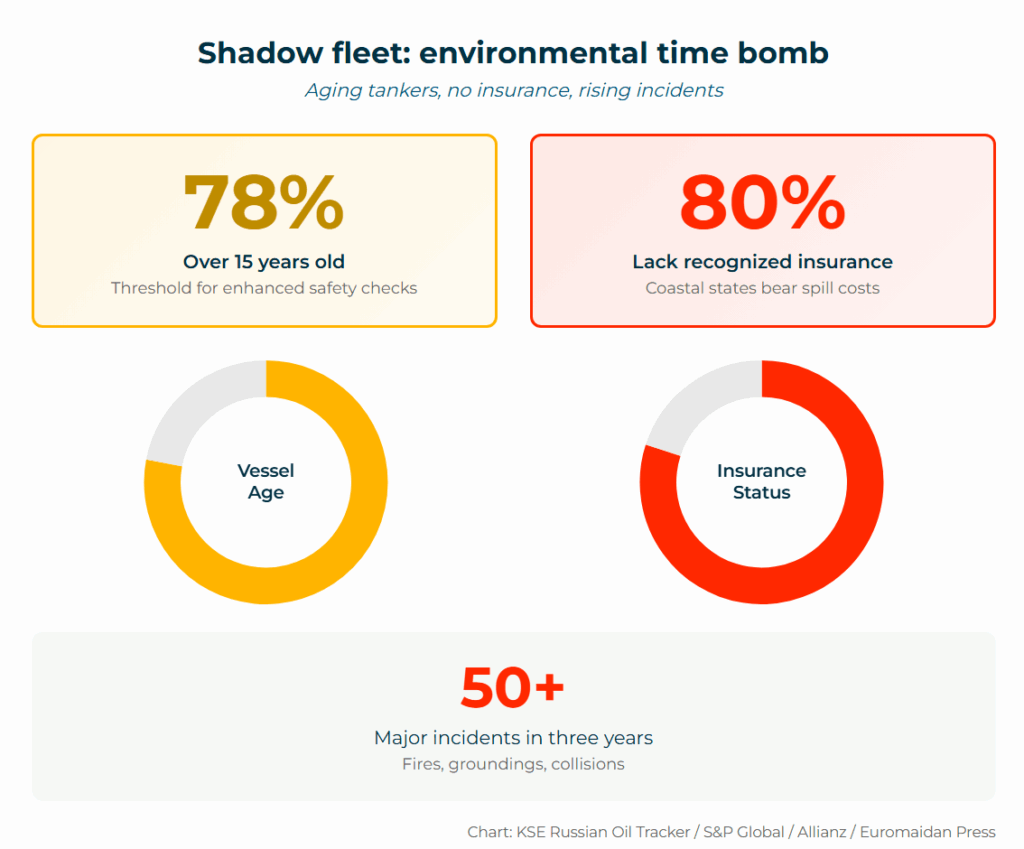

Beyond stranded revenue, 140 million barrels at sea are an environmental liability. According to the Kyiv School of Economics’ December 2025 Russian Oil Tracker, 78% of shadow fleet tankers departing Russian ports were older than 15 years—the threshold at which international maritime rules require enhanced safety assessments.

In December 2024, the tanker Eagle S severed the Estlink-2 power cable between Finland and Estonia after dragging its anchor.

Up to 80% of tankers carrying Russian oil lack recognized insurance from the International Group of P&I Clubs—the consortium covering 90% of global shipping—S&P Global analysts estimate, meaning any major spill would leave coastal states to bear cleanup costs.

The pattern of incidents is accelerating: Allianz’s Safety & Shipping Review 2025 documented more than fifty major incidents over three years, including fires, groundings, and collisions. In December 2024, the tanker Eagle S severed the Estlink-2 power cable between Finland and Estonia after dragging its anchor.

The shadow fleet’s crisis is Russia’s to solve—and the options are narrowing.

“A major environmental disaster is only a question of time,” the Kyiv School of Economics warned. A tanker spill in busy chokepoints like the Baltic, Mediterranean, or English Channel would leave coastal states facing cleanup costs that no shadow fleet insurer could cover.

The shadow fleet’s crisis is Russia’s to solve—and the options are narrowing. China’s independent “teapot” refineries—small-scale operations outside the state-controlled sector, so named for their initially modest size—may absorb some rejected barrels, but at steeper discounts that further erode Kremlin revenues.

Ukraine claims coordinated pressure has already forced 20% of the shadow fleet offline, with current restrictions projected to cost Moscow $30 billion annually. The Grinch was just the beginning—and the Huihai Pacific and Adonia suggest more tankers may soon face a choice: turn back, or be boarded.