Can Europe defend itself? Finnish President Alexander Stubb’s answer at Davos last week was “unequivocally yes”—even without the Americans, if it came to that. But then came the follow-up: Do Finland’s F-18 fighters fly without American support? “No, they don’t.” Do the F-35s Finland is acquiring? Same answer.

“But do we trust that they will continue to fly because it’s in the interest of America to do so? Yes,” Stubb said.

That tension—Europe could manage if forced to, but prefers not to test it—captures the dilemma now confronting European capitals. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte made it explicit on 27 January, telling EU parliamentarians in Brussels that anyone who believes Europe can defend itself without the United States should “dream on.”

Two price tags, not one

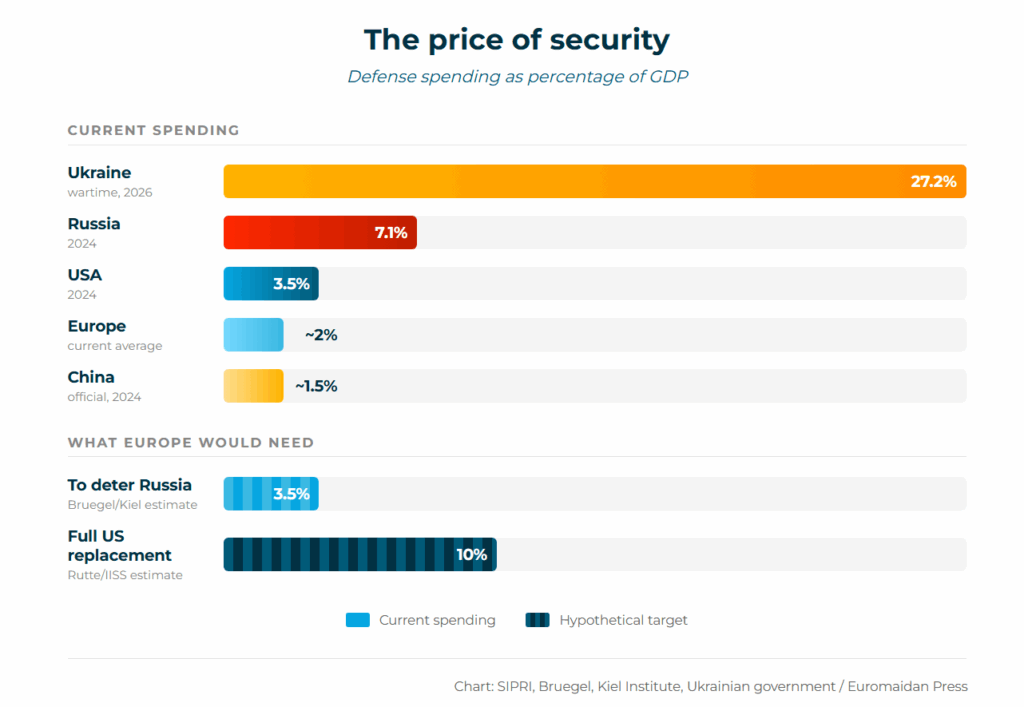

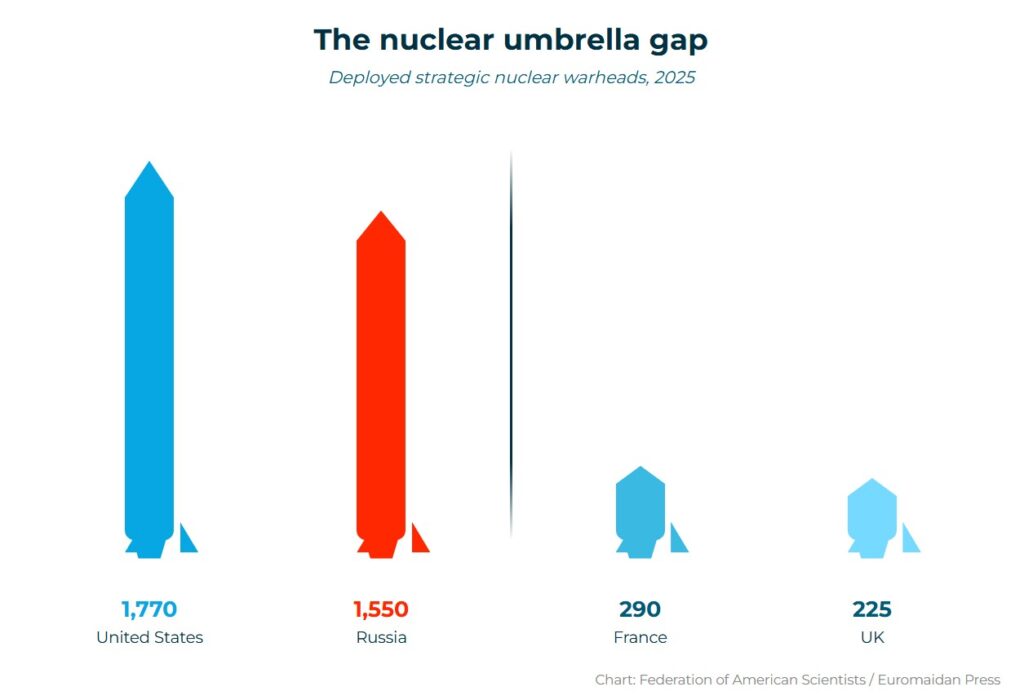

Rutte’s math was stark. If Europe truly wanted to replace all American military capabilities—stealth aircraft, nuclear umbrella, global intelligence—defense spending would need to reach 10% of GDP. Building an independent atomic deterrent alone would cost “billions upon billions of euros.” His verdict: “We can’t do it.” The one-time price tag for replacing US capabilities: roughly €1 trillion, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

What would it cost to deter Russia specifically, without relying on American troops in a crisis?

But that’s not the question Europeans actually need to answer. The real question is: what would it cost to deter Russia specifically, without relying on American troops in a crisis?

The answer, according to researchers at the Bruegel think tank and Kiel Institute: €250 billion in additional annual spending, raising Europe’s defense budget from roughly 2% to 3.5% of GDP. “In economic terms, this is manageable,” said Guntram Wolff, co-author of the analysis. “Far less than had to be mobilized to overcome the crisis during the Covid pandemic.”

That €250 billion figure would pay for 300,000 additional troops and the weapons to equip them. It would not, however, replace the American nuclear umbrella—the “ultimate guarantor” of European security, as Rutte put it at Davos. Without that, he told MEPs, Europe should wish itself “good luck.”

Rutte was equally dismissive of proposals for a European army. Such a force would create “a lot of duplication,” he warned. “It will make things more complicated. Putin would love it.”

What Europe is building

The continent’s defense awakening is real, even if incomplete. Europe is building weapons factories faster than at any time since World War II—Rheinmetall alone has opened or is constructing 16 new plants since Russia’s 2022 invasion. The continent’s defense industry output hit €183 billion last year.

Markets grasped the shift before governments did.

EU defense spending is projected to reach €381 billion in 2025—an 11% increase from 2024 and a 63% increase from 2020. Rheinmetall will soon produce 1.5 million 155mm artillery shells annually—more than the entire American defense industry combined.

Markets grasped the shift before governments did. Michael Herzog, then a trader at Davidson Kempner Capital Management, began buying Rheinmetall shares in February 2022 as Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine. The stock has since risen over 1,700%. When he presented his thesis to 40 investment managers in late 2024, only five held the stock. It has since tripled.

MBDA, the continent’s largest missile maker, has quadrupled the output of short-range Mistral air-defense missiles.

“People still think Europe won’t spend the money,” Herzog told Bloomberg. “Events will force Europe to do this.”

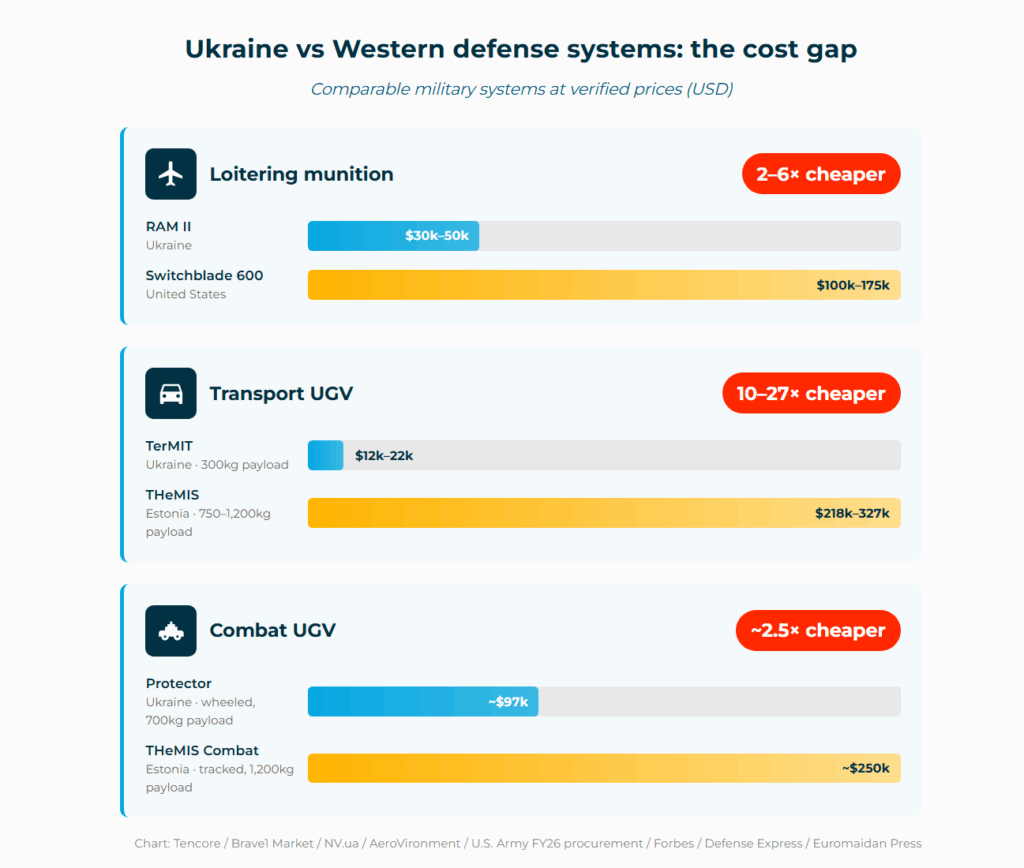

European missile production has surged. MBDA, the continent’s largest missile maker, has quadrupled the output of short-range Mistral air-defense missiles. Estonian company Milrem Robotics, which describes itself as “the world leader in autonomous unmanned ground vehicles,” now supplies its THeMIS combat drones to 19 countries, including eight NATO members.

But its sophisticated systems—designed for well-funded professional armies with time for extensive training—embody a tension visible across European defense. Ukrainian ground robots cost $10,000–22,000 and are already evacuating 80% of wounded soldiers and striking enemy positions; a Ukrainian commander says Western equivalents cost $400,000 and “mostly do not pass field tests.” Ukraine’s 3rd Assault Brigade runs an entire logistics operation using only UGVs—a world first.

What Europe cannot build—yet

Where Europe excels at scaling proven systems, it struggles to build the capabilities that would let it fight without American support. Europe is at least a decade away from producing its own stealth fighter. Despite Germany inventing the ballistic missile over 80 years ago, the continent has almost no production of long-range missiles. Strategic air defense and satellite intelligence remain American domains.

Poland’s decision to buy nearly 1,000 tanks and 672 howitzers from South Korea underscores Europe’s production bottleneck.

The F-35 dependency illustrates the problem. Thirteen European nations have ordered the American stealth jet. Finland alone is receiving 64 aircraft. But as Stubb acknowledged at Davos, these planes—like Finland’s current F-18s—require American spare parts, software updates, and support to fly. His confidence rests on trust that America will maintain that support because it serves American interests too—a reasonable bet, but still a bet.

Poland’s decision to buy nearly 1,000 tanks and 672 howitzers from South Korea—a $14.5 billion deal signed in 2022—underscores Europe’s production bottleneck. Estonia has followed the same path, purchasing 36 South Korean K9 howitzers for €120 million.

“The fact that Poland, which is the closest Ally to the US you can find, is buying in South Korea, is because they cannot buy enough in the US or in the European” markets, Rutte explained at Davos.

Ukraine as a partner and a limit case

Trending Now

Ukraine has become both a proving ground and a partner in European rearmament. Through June 2025, European manufacturers allocated at least €35.1 billion in military aid to Ukraine via new defense procurement contracts—€4.4 billion more than the United States.

“Europe has now procured more through new defense contracts than the United States—marking a clear shift away from drawing on arsenals toward industrial production,” noted Taro Nishikawa of the Kiel Institute.

The EU’s €150 billion SAFE defense initiative explicitly includes Ukraine in joint procurement, recognizing that Kyiv scaled its defense industry from $1 billion to $35 billion in three years.

Rutte urged EU members not to restrict the bloc’s €90 billion loan to Ukraine to European-made weapons only.

But Ukraine also reveals Europe’s limits. Kyiv desperately needs Patriot air defense interceptors—systems only America produces in sufficient quantity. As Ukrainian analyst Mykola Bielieskov told the Wall Street Journal: American air defenses “are invaluable, and the country can’t get enough of these systems’ interceptors.”

Rutte urged EU members not to restrict the bloc’s €90 billion loan to Ukraine to European-made weapons only. Europe’s defense industry “cannot deliver nearly enough of what Ukraine needs today for defense and tomorrow for deterrence,” he warned.

The nuclear question

The most sensitive gap is nuclear. French President Emmanuel Macron opened a “strategic debate” in March on extending France’s nuclear umbrella to European allies—responding to German Chancellor-designate Friedrich Merz’s call to discuss how French and UK nuclear forces “could also apply to us.”

Whether France’s force can credibly deter Russia on behalf of Poland, the Baltics, or Germany remains an open question.

But France possesses around 290 atomic warheads; the UK has 225. Combined, Europe’s nuclear powers hold roughly 515 warheads. The American strategic arsenal numbers 1,770 deployed weapons.

Whether France’s force—or even both European arsenals together—can credibly deter Russia on behalf of Poland, the Baltics, or Germany remains an open question, and one that no amount of conventional spending can answer.

The trade-off ahead

The NATO chief has been explicit about what increased defense spending requires. “On average, European countries easily spend up to a quarter of their national income on pensions, health and social security systems,” he stated in December 2024. “We need a small fraction of that money to make our defences much stronger.”

Ukraine’s 2026 budget allocates 27.2% of GDP to defense—not because Kyiv chose sacrifice, but because Russia left it no alternative.

That trade-off—retirement security versus military security—will define European politics for the coming decade. Ukraine’s 2026 budget allocates 27.2% of GDP to defense, with 100% of domestic revenues going to national security—not because Kyiv chose sacrifice, but because Russia left it no alternative.

A record 955 billion hryvnias ($23 billion) is earmarked for weapons procurement alone. That is what war costs. Europe’s challenge is whether it can muster the political will to spend the €250 billion annually—the sum Bruegel and Kiel researchers say would deter Russia—to ensure it never faces the same choice.