Same week in January 2026: Bucharest, an EU capital at peace, leaves 3,500 apartment buildings without proper heat after a single boiler failure. Kyiv, under daily Russian missile strikes, restores heat to 5,600 buildings within six days of its worst attack of the war.

What gets rebuilt in Ukraine will determine whether 26 million people remain vulnerable to energy blackmail—or escape it.

What gets rebuilt in Ukraine will determine whether 26 million people remain vulnerable to energy blackmail—or escape it—until the 2050s. Western governments are funding that reconstruction. The choice being made now isn’t just about pipes. It’s about whether Russian attacks on infrastructure remain strategically effective for another generation.

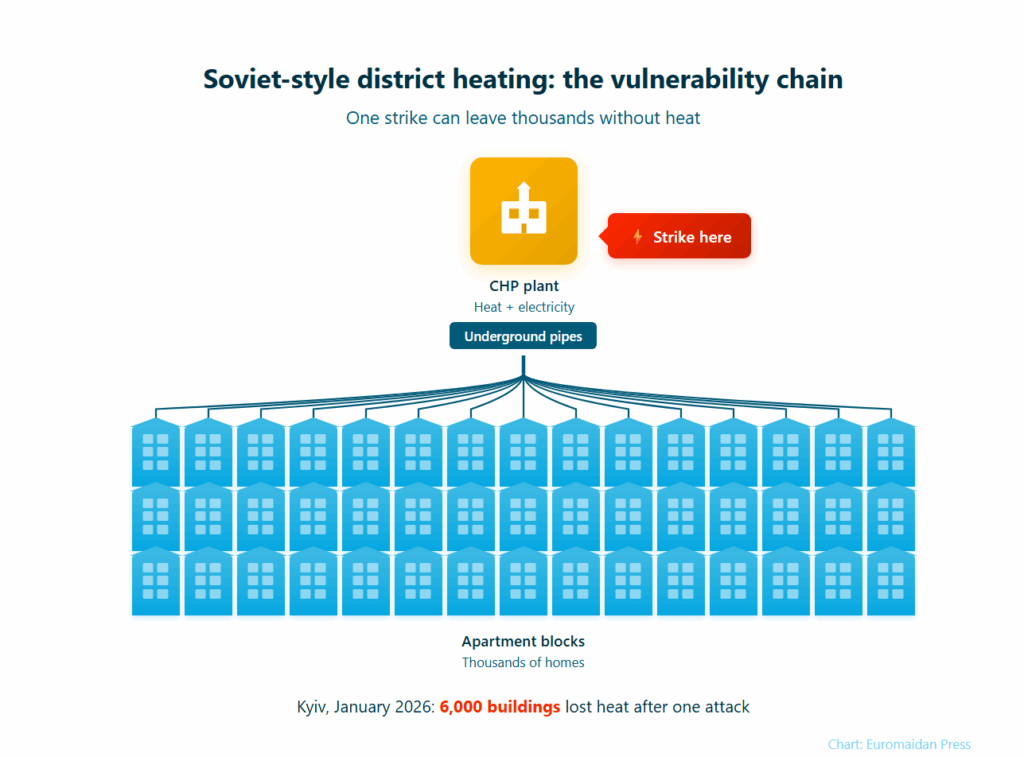

One plant, thousands of buildings

Most Americans heat their homes with individual furnaces. You control your thermostat, pay your bill, call your repairman.

Denmark and Finland have higher district heating penetration than any former Soviet state.

The Soviets built something different: one massive plant pumps hot water through kilometers of underground pipes to entire neighborhoods. You don’t control when heat arrives. Officials decide. You pay based on apartment size, not usage. Moscow’s system stretches 16,600 kilometers. Bucharest’s is 4,000 kilometers—the world’s second-largest. Kyiv’s covers 2,800 kilometers.

When maintained, these systems work. Denmark and Finland have higher district heating penetration than any former Soviet state.

The problem is what happens when investment stops.

How Bucharest’s system collapsed

Romania inherited its district heating from the Ceaușescu era. Most pipes date from the 1960s to 1985 and haven’t been replaced.

The system has a structural flaw beyond age: split governance. ELCEN, the company that produces heat, reports to the Ministry of Energy. Termoenergetica, the company that distributes heat, reports to Bucharest City Hall. Different budgets. Different political parties. When pipes burst, blame follows.

“When it comes to heating, the insults go to the mayor, not the minister.”

“There are very large financial losses between Termoenergetica and ELCEN, because one is at the Ministry of Energy and the other at the City Hall,” Bucharest Mayor Ciprian Ciucu explained this week. “When it comes to heating, the insults go to the mayor, not the minister.”

The decay is measurable. Daily losses now equal the heat needed for 75,000 apartments, according to Energy Minister Bogdan Ivan, as reported by Știri pe Surse. The EU’s Cohesion Fund provided €216 million ($251 million) to replace 105 kilometers of pipes—about 22% of the critical hot-water transport route. The network is failing faster than it can be fixed.

“If they had turned on the hot water boiler that feeds 3,500 buildings, it risked exploding.”

When a boiler at CET Sud failed this January, engineers couldn’t increase pressure from other plants to compensate. The old pipes couldn’t handle it. “If they had turned on the hot water boiler that feeds 3,500 buildings, it risked exploding,” Ciucu said. The system now operates “in emergency mode.”

“In such a mega-system, you need to intervene with 2-3% every year,” Ciucu acknowledged. “If every mayor had directed the money—1-2% per year—to replace pipes, we wouldn’t have gotten here.”

They didn’t.

“A commendable switch”

Lithuania inherited the same Soviet infrastructure. In 2011, only 23% of its district heating came from renewable sources. The rest burned Russian natural gas.

Six years later, renewable sources provided 66%—a transformation the Lithuanian District Heating Association called “a world record in speed and dimension.”

Lithuania opened its heat market to independent producers.

What changed? Policy, not technology.

Lithuania opened its heat market to independent producers. It switched from imported Russian gas to domestic biomass—wood chips from forestry by-products. It invested EU Structural Funds in modernizing pipes and adding cogeneration capacity. The International Energy Agency (IEA) called it “a commendable switch” that reduced emissions, imports, and costs simultaneously.

The difference between Lithuania and Romania isn’t geography or luck.

Estonia followed a similar path. Utilitas, the country’s largest district heating company, now heats 174,000 homes using domestic wood chips, operates three cogeneration plants, and uses AI-based pattern recognition to forecast consumption.

Trending Now

The difference between Lithuania and Romania isn’t geography or luck. It’s whether governments treated district heating as infrastructure requiring continuous investment—or as a political problem to defer.

What Ukraine is building

Ukraine’s district heating serves 26 million people. Russian strikes have turned this into a strategic vulnerability. Hit one combined heat and power (CHP) plant, and thousands of buildings lose heat simultaneously.

Kyiv’s January 2026 crisis proved the point. Mayor Vitali Klitschko called it “the most severe crisis in four years of full-scale war.” Six thousand buildings lost heat; 400 remained without it six days later.

Kyiv’s worst blackouts force rivals Zelenskyy and Klitschko into same chain of command (INFOGRAPHIC)

“Instead of replacing hundreds of kilometers at once, they repair tens—30, 40, 80 kilometers per year,” energy expert Oleh Popenko told Euromaidan Press. “During frosts and strikes, the city gets a ‘chain effect’ of accidents.”

But Ukraine isn’t just patching the old system. It’s decentralizing.

“A transition to a green and decentralized energy system is a matter of national security.”

“New decentralized generation facilities, in particular cogeneration plants, will increase the energy resilience of communities,” Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko said in December 2025. “They can produce both heat and electricity simultaneously, ensuring decentralization and additional resilience during power outages.”

Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha put it more bluntly at the UN General Assembly: “A transition to a green and decentralized energy system is a matter of national security.”

The numbers show movement. According to government data reported by New Eastern Europe, Ukraine’s district heating sector operates 182 cogeneration units with a combined capacity of 147 MW, plus 239 block-modular boilers adding about 635 MW.

The war has transformed the question from “modernize” to “rebuild how?”

Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the EBRD had approved €140 million ($162 million) in 2021 for Kyiv’s heating modernization. The war has transformed the question from “modernize” to “rebuild how?”

The financing gap is staggering. Ukraine’s Ministry of Territories and Communities Development estimated the cost of modernizing district heating at $6 billion before Russia’s invasion. The war has added $2.5 billion in damage.

Housing reconstruction alone now requires $84 billion. Current programs operate at a fraction of that scale—Ukraine’s Energy Efficiency Fund has completed 315 projects worth €22 million ($25 million) total since launching in 2019.

Three paths visible

Heating infrastructure operates for 20-30 years. What Ukraine installs during reconstruction determines its vulnerability until the 2050s.

Romania shows what happens when you inherit the system without reforming it: decades of deferred maintenance, split governance that prevents accountability, and eventual collapse even without external attack.

The question is whether investment matches rhetoric.

Lithuania shows escape is possible: clear policy direction, market competition, fuel switching, real investment.

Ukraine is choosing in real time, under fire. The policy direction is clear—“decentralization” appears in nearly every official statement. The question is whether investment matches rhetoric.

“Energy independence is not just a long-term strategy for Ukraine; it is a necessity.”

“Energy independence is not just a long-term strategy for Ukraine; it is a necessity for recovery right now,” First Deputy Minister Alona Shkrum said at the signing of a €16.5 million ($19 million) renewable energy agreement in October 2025.

The systems being installed today will still be running when the children born during this war have children of their own.