Kyiv promised 100 MW of cogeneration capacity to survive this winter. Equipment worth 1.2 billion hryvnias ($29 million) ordered in 2024 remains “in installation phase”—officials have only obtained “technical conditions for connection.”

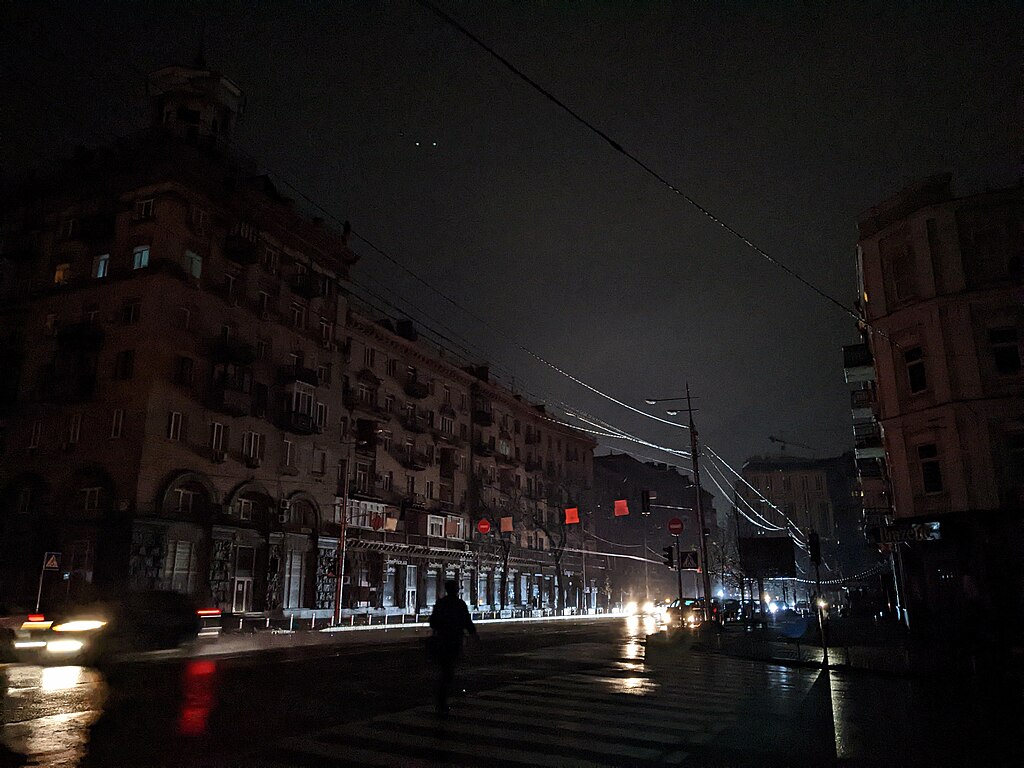

On 11 January, Russian drones hit critical infrastructure across Ukraine. Kyiv faced emergency blackouts. Zhytomyr, 140 kilometers west, kept its lights on longer.

The contrast sparked outrage on Ukrainian social media. Ihor Lutsenko—former MP, founder of Ekonomichna Pravda, now a military drone operator—highlighted a year-old investigation into how Zhytomyr built what Kyiv keeps promising.

Any country facing infrastructure attacks confronts the same question: centralized systems that can fail catastrophically, or distributed ones that degrade gracefully?

“The secret is that if you have the will—west of Ukraine there is still an ocean of opportunities to receive help from international organizations, in the form of grants, interest-free loans, and low-interest credits. Come and take it,” he wrote on Glavcom.

LB.ua confirmed on 8 January that Kyiv had missed its December deadline. Three days later, a drone attack injured two Zhytomyr utility workers and sparked fires—but distributed generation meant no citywide blackout.

The lesson extends beyond Ukraine. Any country facing infrastructure attacks—from Russian missiles to cyberwarfare to natural disasters—confronts the same strategic question: centralized systems that can fail catastrophically, or distributed ones that degrade gracefully?

What Zhytomyr actually built

By August 2025, Zhytomyr Oblast had installed 13 cogeneration units generating 5 MW, according to Zhytomyr.info. Six operate in the city itself. A private investor, UKRPALET ENERGI, added another 11.5 MW across five sites.

The city cut gas consumption from 100 million cubic meters a decade ago to under 50 million today. Its water utility slashed electricity use by 27% after replacing old pipes. LED streetlights halved municipal lighting costs.

When the water utility director wants one thing and deputies want another, nothing works.

Deputy Mayor Serhiy Kondratyuk explained the formula to Texty last January: alignment between the city council, utility managers, and technical staff. “If these three are together, everything works. When the water utility director wants one thing and deputies want another, nothing works.”

Zhytomyr didn’t have more money than Kyiv. It had a strategy. Cut consumption first. Then build generation. USAID provided cogeneration units. The EBRD funded the pipe replacement. The World Bank financed water upgrades. Switzerland helped build Ukraine’s first woodchip-fired power plant. Each project built on the last.

Kyiv took a different path. Mayor Vitali Klitschko announced ambitious targets. The city ordered 15 units totaling 60 MW. But in autumn 2025, procurement data showed Kyivteploenergo was still ordering concrete shelters for equipment that hadn’t arrived.

One missile, one blackout—or not

Volodymyr Kudrytskyi, the former Ukrenergo chairman dismissed in September 2024, explained the math in a December interview with Euromaidan Press: “The formula of this energy war is: you must recover more quickly than your adversary is able to destroy.”

Why does Ukraine’s grid survive missiles that would black out Europe? Ousted energy chief explains

Trending Now

Russia targets concentration. One missile can disable a thermal plant serving millions. But hitting dozens of small generators scattered across boiler houses, hospitals, and water utilities would require hundreds of precision strikes. Decentralization changes the economics of destruction.

The same logic applies to any nation worried about grid resilience—whether from state attacks, terrorism, or climate disasters. Small, redundant, locally controlled beats large, efficient, centrally dependent. Ukraine is learning this the hard way. Others could learn it cheaper.

A governance test, not a resource test

Andrii Kulibaba, coordinator of the Public Integrity Council—the civic body that vets judges for corruption—offered a blunt verdict on Kyiv in a Facebook post: “The authorities lack capacity—above all, intellectual capacity. There is no long-term policy, no execution discipline, no desire to take responsibility.”

The main thing is the connection between deputies, utility workers, and managers.

The data support him. Kyiv Oblast (the region surrounding the capital, governed separately) now operates 51 small generation facilities totaling 110 MW.

Chernivtsi got two cogeneration units from the German development agency GIZ in June. Berdychiv and Zviahel are installing their own. The international funding exists. The technology exists. What varies is whether local officials actually use it.

Kondratyuk’s advice: develop a strategy first, involve people who understand the systems, then seek financing. “There are many opportunities today. The main thing is the connection between deputies, utility workers, and managers.”

Western donors debating whether Ukraine can absorb aid effectively should note the split. Some cities execute. Others announce. Zhytomyr built resilience. Kyiv built press releases.

Read also

-

Russia deliberately waited for temperature to drop to -15°C to maximize suffering of Ukrainians. And send message to Europe

-

Russia launches 156-drone attack: Kyiv fire, Odesa blackouts, Zhytomyr trains halted

-

Parts of Berlin still without power after sabotage—Ukrainians organize one of the warming shelters