Both may be right—and that’s exactly the problem.

“Russia has the upper hand. And they always did. They’re much bigger and stronger,” US President Donald Trump told Politico on 9 December, urging Ukraine to “start accepting things” in peace negotiations.

Euromaidan Press’s 2026 outlook is that Russia’s military weight is real—but its ability to finance this war is heading into its tightest year yet.

That same week, economists delivered a starkly different assessment. Russia is in “the worst situation since the war started,” Janis Kluge of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs told the Washington Post. A Russian official, speaking anonymously to the same outlet, warned that “a banking crisis is possible” in 2026.

Both assessments contain truth: Russia retains military momentum while its economic foundation crumbles.

The question determining Ukraine’s fate is which clock runs out first—and whether the West maintains pressure long enough to find out.

The numbers behind the contradiction

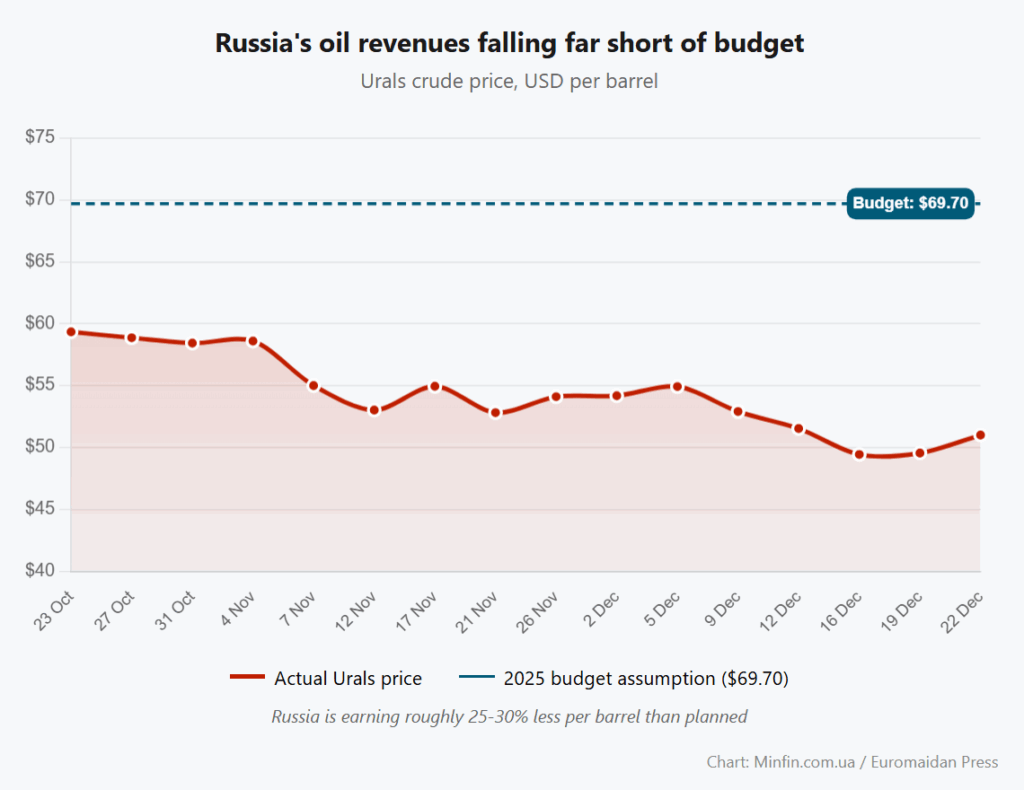

Russia’s 2025 budget assumed oil would sell at $69.70 per barrel. As of mid-December, Urals crude from the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk was trading at $34.52—roughly half the budgeted price, according to the Moscow Times, citing Argus Media data. The discount to benchmark Brent has widened to $23 to 25 per barrel, the largest gap since early 2023.

The revenue collapse is immediate.

Oil and gas earnings fell 34% year-on-year in November, according to Russia’s Finance Ministry data cited by the Washington Post. December receipts could drop 49% below 2024 levels, to roughly $5.1 billion, the lowest since the pandemic.

“As long as Russia produces oil and sells it at a relatively good price, it has enough money to stay afloat,” Richard Connolly of the Royal United Services Institute told Tagesspiegel. The question is whether current prices still qualify as “good enough.”

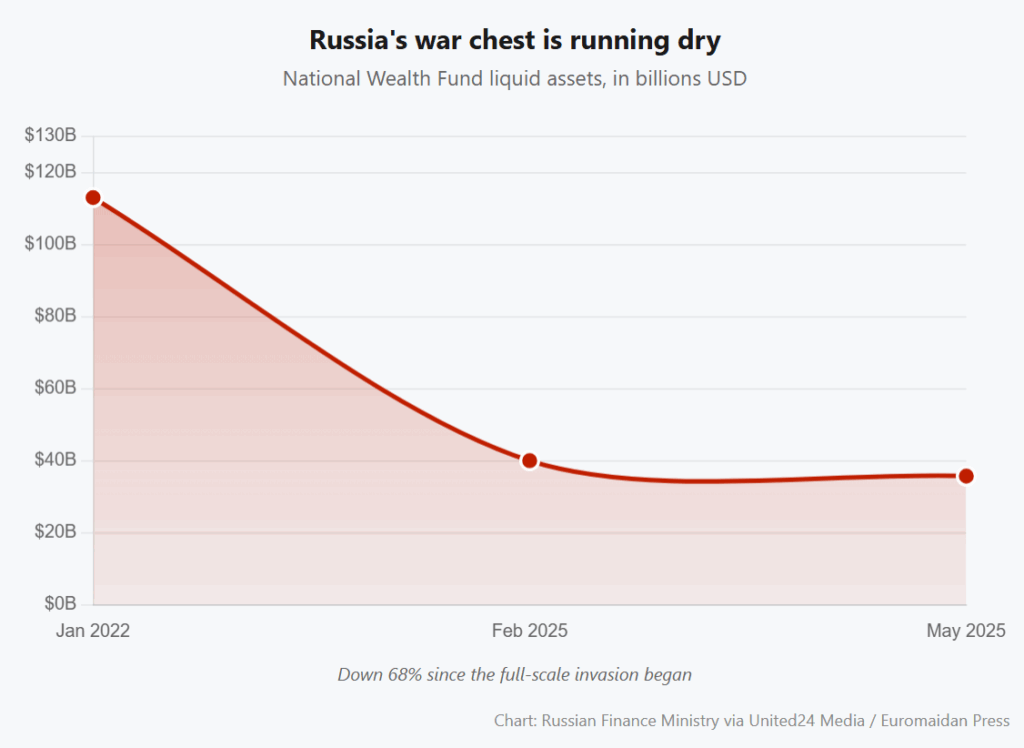

The liquid assets of the National Wealth Fund, Russia’s emergency reserve, have shrunk from $185 billion in 2021 to $35.7 billion.

For comparison, Ukraine’s budget deficit stands at roughly 19% of GDP, but EU leaders agreed on 19 December to provide Kyiv with a €90 billion ($106 billion) interest-free loan for 2026-2027—backed by common EU borrowing and repayable only after Russia pays war reparations. Moscow asked China for similar macroeconomic support. Beijing refused.

January brings a tax shock

Russia enters 2026 caught between contradictory policies. The Central Bank just cut interest rates from 16.5% to 16%—the fifth reduction from a record 21% peak—to save businesses strangled by borrowing costs.

However, on 1 January, Moscow raises the VAT rate from 20% to 22% and reduces the exemption threshold from 60 million rubles ($731,000) to just 10 million rubles ($122,000) in annual revenue. Approximately 450,000 small businesses will lose their VAT exemption overnight.

The result: more companies are dying than being born.

Registered businesses in Russia fell to 3.17 million by September—the lowest since 2010, according to Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service. The World Bank downgraded Russia’s 2026 growth forecast to 0.8%.

Ukraine, by contrast, is forecast to grow by 1.9% in 2025 and 2% to 3% in 2026-2027 under current conditions, according to the National Bank of Ukraine—though international institutions project a faster recovery if the fighting stops.

Trending Now

Why does Russia keep on fighting?

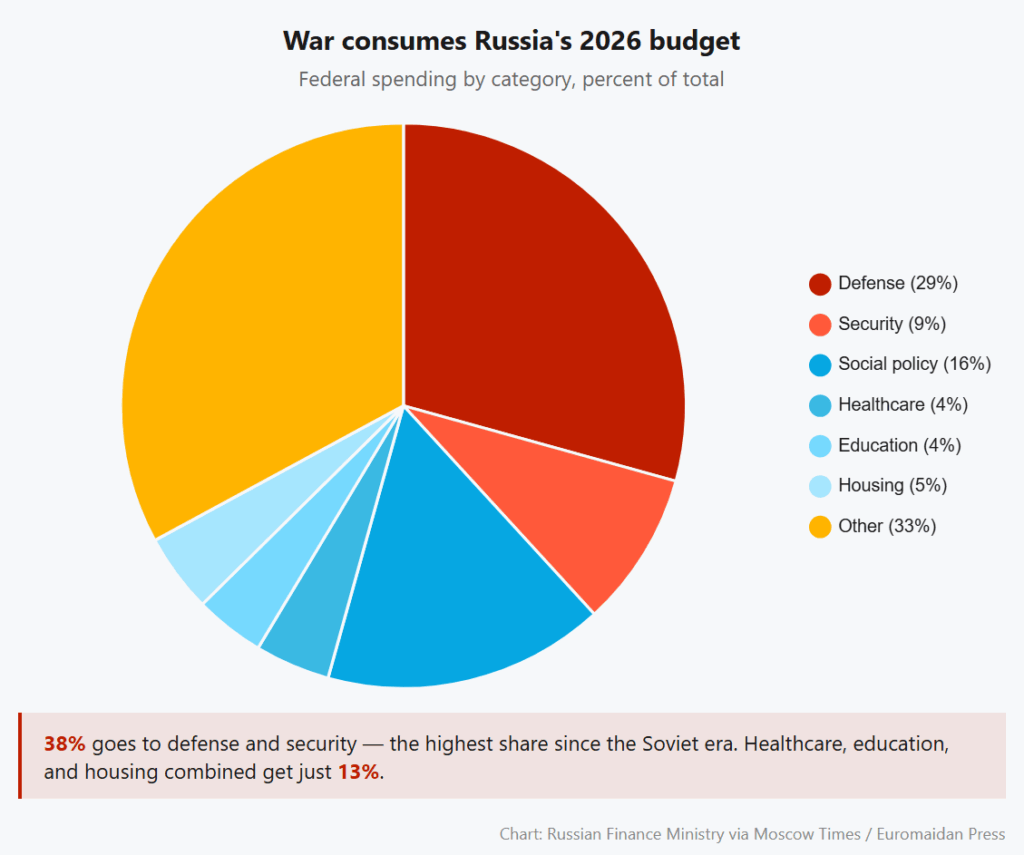

Economic pain hasn’t translated into military constraint yet. Russia plans to spend $183 billion on defense and security in 2026—nearly 40% of federal expenditures, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte said earlier this month.

Defense industry expert Anatolii Khrapchynskyi said that Moscow now produces roughly 20% more weapons than the front requires, holding the surplus for “potential operations in Europe.”

The explanation lies in who bears the cost. About 20% of Russia’s population earns income connected to military service or war production—their wages have increased substantially. The other 80% are watching purchasing power evaporate, Ukrainian economist Volodymyr Vlasiuk explained to Euromaidan Press two months ago.

“Russians never lived well anyway,” Khrapchynskyi noted. “The money just went not to the oligarchs but to the war.”

The 12-18 month window

Vlasiuk, analyzing Russian budget data for Euromaidan Press in October, calculated a much shorter runway: 12-18 months before Moscow faces a twofold choice—reduce military spending or face fiscal collapse.

The divergence stems from assumptions about external support. If China reverses course or Western sanctions weaken in a peace deal, Russia’s timeline extends indefinitely.

Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s prime minister, said Russia should be “reintegrated” into the world economy once fighting ends—a prospect economists warn would rescue Putin from the very trap sanctions created.

For now, both exits remain blocked. China has exploited Russia’s desperation rather than rescued it. Russian LNG is selling to China at 30-40% discounts, according to Reuters. At the same time, India’s crude imports from Russia are projected to fall to 600,000-650,000 barrels per day—a three-year low—as refiners avoid newly sanctioned Rosneft and Lukoil cargoes.

What would force Putin to negotiate?

Not inflation alone. Richard Connolly explained to Tagesspiegel that, unlike Western democracies, high inflation in Russia doesn’t trigger “great social dissatisfaction”—Russians are accustomed to it from the post-Soviet era, and state propaganda suppresses dissent.

But the Atlantic Council warns that continued depletion of the National Wealth Fund could eventually force cuts to social spending — a step that would be “visible” to ordinary Russians in ways current inflation is not. And a senior Russian official warned The Washington Post that a banking crisis could hit very soon—and that would be harder to hide.

Trump says Russia has the upper hand. Western economists see an economy burning through reserves faster than it can replenish them. The €90 billion EU loan buys Ukraine two years; Russia’s depleting war chest offers no such guarantee. In a war of attrition, 2026 may determine which clock runs out first.