Russia has effectively switched on the “printing press” to plug a budget hole approaching 6 trillion rubles ($76.8 billion), while its largest commercial employer drowns in debt, oil revenues crater, and supposed allies extract billions in discounts from Moscow’s desperation.

A cascade of economic indicators in late November 2025 reveals the mounting strain on Russia’s war-distorted economy—suggesting the costs of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine are finally overwhelming the Kremlin’s financial defenses.

The money-printing scheme

Russia’s federal budget faces a deficit that could reach 6 trillion rubles ($76.8 billion) by year’s end, and authorities are covering the gap through what analysts describe as disguised monetary emission.

The Finance Ministry has been issuing government bonds (OFZ) at unprecedented volumes. Banks purchase them—but not with their own money. The Central Bank provides weekly loans secured by these same bonds, creating a circular financing scheme that has already exceeded 2.8 trillion rubles ($35.9 billion).

The maneuver reflects Moscow’s isolation from international capital markets. After the invasion, Russian sovereign debt became toxic to foreign investors. Major funds and banks cannot legally purchase Russian securities, leaving the Kremlin to squeeze domestic institutions for ever-larger bond purchases.

“Russia is not able to borrow money internationally due to sanctions—even China is not ready to provide access to its domestic financial market,” the Free Russia Foundation noted in its analysis.

Plans to issue yuan-denominated bonds were quietly dropped in May 2025 after facing regulatory resistance from Beijing.

Russians flee to cash

The financial system’s fragility is triggering a public response. Between July and September, Russians withdrew 659 billion rubles ($8.4 billion) in cash—nearly five times the amount during the same period in 2024.

The Central Bank has linked this surge to recurring internet outages that began spreading across Russia in May, initially as anti-drone measures but now affecting more than 50 regions. The Ulyanovsk region has cut mobile internet entirely until the war ends.

But distrust runs deeper than connectivity problems.

Stricter banking controls introduced on 1 September have made Russians wary of digital transactions, fearing account freezes and payment delays. Since 1 July, the tax service gained authority to inspect bank accounts as part of anti-evasion efforts—prompting many to shift savings into cash.

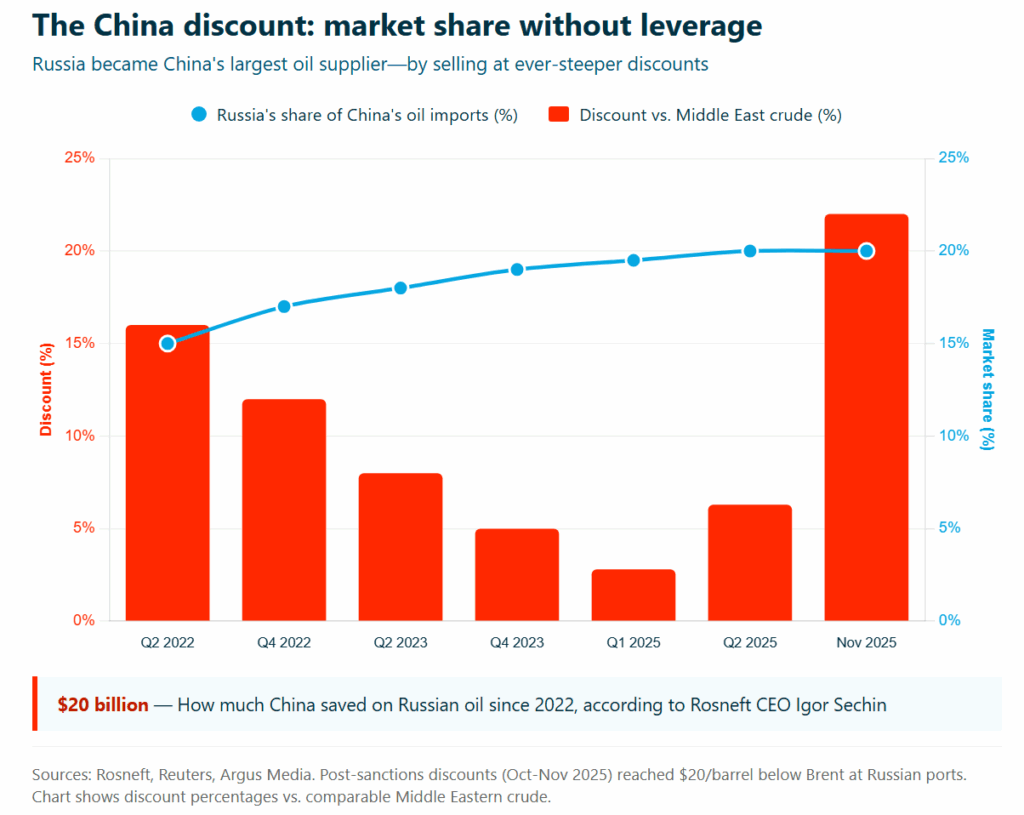

Putin’s $20 billion gift to Beijing

China has saved approximately $20 billion on Russian oil purchases since 2022, according to Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin—who framed Moscow’s fire-sale pricing as Chinese “procurement efficiency” at a Beijing energy forum on 25 November.

The admission amounts to acknowledging Russia’s losses.

Discounts on Russian crude peaked at 16% below Middle Eastern alternatives in summer 2022. They narrowed to 5% by late 2023, but have surged again in 2025: 2.8% in the first quarter, 6.3% in the second, and far higher after October’s US sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil pushed Urals crude to $20 below Brent at Russian ports.

Sechin boasted that Russia supplied nearly 19% of China’s energy imports in 2024—worth approximately $100 billion—making Moscow China’s largest oil supplier with a 20% market share. But market share acquired through desperation pricing is market share without leverage.

Railway giant sinking under debt

Russia’s government is scrambling to rescue Russian Railways (RZD), the country’s largest employer, which has accumulated 4 trillion rubles ($51.2 billion) in debt.

Officials met in late November to discuss how to “save” the company, with another meeting scheduled for December. The debt stood at 3.3 trillion rubles ($42.3 billion) at mid-year and has ballooned by 700 billion rubles ($9 billion) in just six months—though the cause of the rapid increase remains unclear.

Options under consideration include raising freight tariffs, new subsidies, tax breaks, and tapping the National Wealth Fund.

More radical proposals—not yet formally discussed—include capping RZD’s borrowing costs at 9% and converting 400 billion rubles ($5.1 billion) of debt into equity, which would give state banks direct ownership stakes.

RZD employs approximately 700,000 people. The company has already begun cost-cutting: headquarters staff have been asked to take two unpaid days off monthly since August. Freight volumes have fallen for four consecutive years—down 6.7% in the first nine months of 2025 alone.

India slashes Russian oil imports

India’s Russian crude imports are set to hit their lowest in at least three years in December, plunging from 1.65 million barrels per day in October to an expected 600,000-650,000 barrels per day.

The collapse follows US sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil that took effect on 21 November. Bank scrutiny following the latest sanctions has made Indian state refiners cautious, with most major buyers halting orders.

To retain any Indian customers, Russia has been forced to offer Urals at discounts reaching $7 below Brent—the lowest offer in two years. Before the latest sanctions, the gap was half that.

Desperate for buyers, Russia throws India its biggest oil discounts yet (INFOGRAPHIC)

Trending Now

Indian banks are cautiously returning to financing Russian oil transactions—but only from non-sanctioned sellers, with settlements in UAE dirhams or Chinese yuan, and after exhaustive verification of production sites, vessel histories, and any links to blocked entities. The complexity transforms every Russian shipment into a bureaucratic obstacle course.

China profits from Russia’s dependence

China has nearly doubled prices on export-controlled goods sold to Russia—many with military applications—according to research by the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies (BOFIT).

Between 2021 and 2024, prices for these goods rose by 87% for Russian buyers, compared to just 9% for buyers from other countries. A senior Western sanctions official told the price surge represents a significant indirect constraint on Russia’s military capacity: “If you increase the price of a good by 80%, you almost halve what they can actually buy.”

The pattern is stark in specific categories. Russian imports of Chinese ball bearings rose 76% in dollar terms between 2021 and 2024—but the physical volume fell 13%. Higher prices, not larger quantities, are inflating trade values.

Even within Russia, officials acknowledge that “friendship without limits” exists only in propaganda. A source close to the Russian government told Reuters: “China does not behave like an ally.”

Oil revenues crater

Russia’s oil and gas revenues in November are expected to fall 35% year-on-year, to approximately 520 billion rubles ($6.7 billion).

For the first eleven months of 2025, energy revenues are projected at roughly $102 billion—a 22% decline from 2024 and far below the $141 billion collected last year. The Finance Ministry initially planned to raise $139 billion from hydrocarbons in 2025 but has already slashed that target to $110 billion.

The average tax price for Russian oil has dropped to $57.3 per barrel from $68.3 a year earlier, while a stronger ruble (averaging 81.1 per dollar versus 91.7 in 2024) further reduces the domestic value of export earnings.

EU tightens the LNG noose

The European Commission has clarified its Russian LNG sanctions—and they proved stricter than many European energy companies expected.

From January 2027, EU companies will be prohibited from importing Russian LNG not only into Europe but also from providing services related to Russian LNG projects.

The ban covers technologies, equipment, engineering support, and investments in new or existing Russian gas facilities. This threatens billions in long-term contracts. TotalEnergies holds agreements for 5 million tons annually from Yamal LNG; Germany’s SEFE has contracts for 2.9 million tons; Spain’s Naturgy for 2.5 million tons. These companies had hoped to redirect volumes to Asian markets after the EU ban—but the service prohibitions complicate that path.

For Novatek, Russia’s largest LNG producer, the consequences extend beyond lost European revenues. Replacing EU volumes in Asia will be difficult given infrastructure limitations, and the UK has announced parallel plans to ban maritime services for Russian LNG exports globally, including insurance.

Limited shipping return

French container giant CMA CGM has partially resumed shipments to Russia—but the move signals caution rather than normalization.

The company’s Singapore-based CNC subsidiary is shipping only foodstuffs—specifically, citrus fruit and coffee—to select customers, describing the activity as “very limited and conducted strictly in accordance with the sanctions regime.”

CMA CGM joins Swiss-based MSC, which maintained minimal Russian operations throughout the war, limited to food, medical, and humanitarian goods. For Russia, the continued distance of global shipping underscores how toxic its market remains.

Death by a thousand cuts

None of these indicators alone signals imminent economic collapse. Russia’s economy has proven more resilient than many Western analysts predicted in 2022.

But the cumulative picture reveals an economy operating under intensifying strain. Budget deficits are being filled through mechanisms that fuel inflation. The country’s largest employers are drowning in debt. Supposed allies are extracting maximum profit from Moscow’s isolation. Oil revenues—still the economy’s backbone—are falling faster than the Kremlin planned.

Russia can sustain these pressures for some time. But every discounted barrel, every overpriced Chinese component, every trillion rubles in railway debt represents resources unavailable for the war in Ukraine.

The Kremlin has options: raise taxes further, cut non-military spending, print more money, or drain remaining reserves. Each choice carries costs that compound over time.