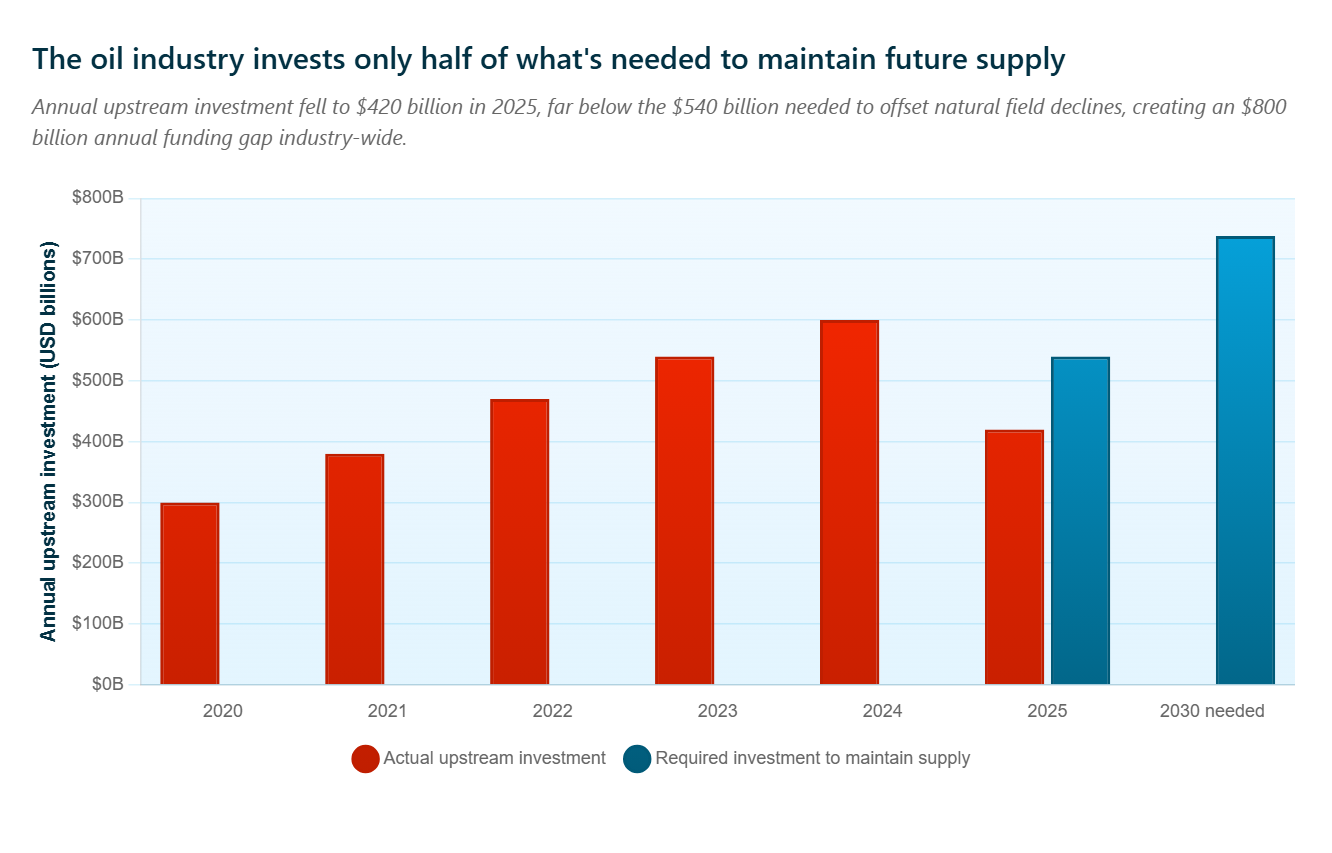

Oil prices dipped to $63.10 per barrel Tuesday as Deutsche Bank forecast a 2-million-barrel-per-day surplus in 2026, but this short-term glut masks a structural crisis: the global oil industry is chronically underinvesting by roughly $800 billion annually—about $2.2 billion every single day—even as natural field declines require 5 million barrels per day of new production yearly to hold output flat.

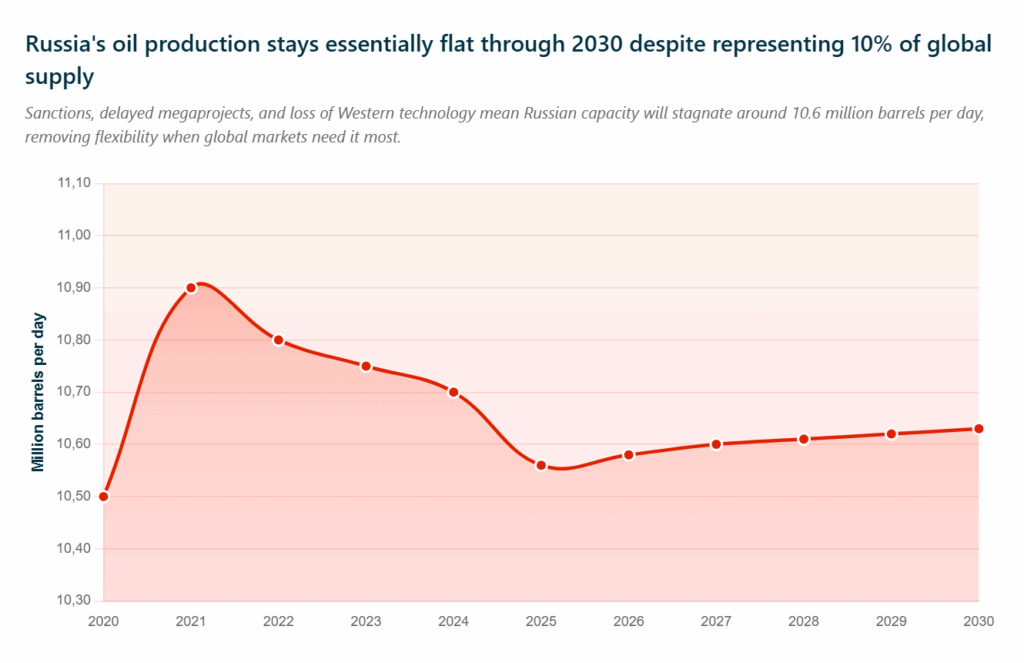

Russia’s sanctions-induced production collapse compounds the timeline.

Russian output fell to 10.70 million barrels per day in 2024, with the International Energy Agency’s forecast showing a further decline to 10.56 million barrels in 2025 and only 10.63 million by 2030—essentially flat, despite Russia representing roughly 10% of global supply.

The massive Vostok Oil project, intended to add 600,000 barrels per day, has been delayed from 2024 to 2026, while Arctic LNG-2 has been scaled back, with its timeline pushed from 2026 to 2028.

The investment crisis hits precisely when global supply needs every available barrel. Industry executives have reported investing only 50% of the necessary capital for over a decade, Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi told the recent ADIPEC conference. Exploration and production investment is falling 6% to around $420 billion in 2025—well below what’s needed to maintain future capacity.

Today’s surplus is tomorrow’s shortage

Conventional oil reserves naturally decline at a rate of around 6% per year, requiring continuous capital deployment to maintain production capacity. The IEA projects that supply capacity growth will reach 1.8 million barrels per day in 2025, then transition to contraction after 2029 as the pipeline of non-OPEC+ projects wanes after 2027.

The current oversupply exists because the global recession has crushed demand, not because supply is abundant to meet future requirements.

If OPEC+ sustains current production rates, global supply could reach 107.2 million barrels daily by 2030—1.7 million barrels higher than projected demand, according to IEA data. Yet this near-term surplus masks post-2027 capacity constraints.

To stem output losses at producing fields, well capital expenditures and field direct operating costs reached nearly 90% of their 2014 highs in 2024—the third-highest level in industry history, IEA reports. These investments are required to maintain the existing supply as natural decline rates erode production capacity.

Investment mandates prioritizing environmental and social criteria now direct two-thirds of the $3 trillion annual energy investment toward renewables.

Major pension funds, including CalPERS and ABP, have implemented divestment policies for fossil fuels, while banking institutions have withdrawn financing for new petroleum developments.

This has created a 2-to-1 capital ratio favoring renewables over fossil fuels, up from roughly a 1-to-1 ratio a decade ago—the result is capital restrictions that persist regardless of price signals that would traditionally spur investment.

Russia’s permanent capacity loss

Western sanctions have devastated Russia’s ability to maintain production infrastructure. War and economic impact have held back Russian investment due to all-time high interest rates, higher corporate taxation, and tight labor markets, while sanctions restrict access to technologies, financing, and supply chain inputs.

Russian crude capacity is projected to fall from 9.53 million barrels daily in 2024 to 9.47 million by 2030. Russia’s inability to access Western drilling technology and spare parts means its production capacity is eroding even as it maintains current output by depleting reserves faster—borrowing from future supply to meet today’s quotas.

Delayed megaprojects, declining field capacity, and technological restrictions ensure that Russian supply won’t recover to pre-war levels even if sanctions are lifted.

The service sector can’t respond quickly

Trending Now

The petroleum service industry faces severe capacity constraints after years of reduced activity. When operators eventually seek to increase drilling, they’ll encounter equipment shortages for modern drilling rigs, workforce limitations from reduced training programs, and extended lead times for specialized systems throughout the supply chain.

These bottlenecks limit rapid response to demand recovery or geopolitical disruptions, even when prices justify increased production.

The shift from conventional to unconventional production has changed industry response times. Conventional oil fields show annual decline rates of 5-15%, with development timelines spanning 5-10 years.

Unconventional shale operations face first-year decline rates of 40-70%, with development compressed to 6-12 months but peak production windows limited to 3-5 years. Shale’s rapid decline rates demand continuous drilling to maintain output, while conventional projects need long lead times that make quick supply responses impossible.

The coming squeeze

For energy-importing nations, current low prices offer false comfort. The structural investment deficit, combined with Russia’s eroding production capacity, creates vulnerabilities that could manifest in supply disruptions and price spikes when post-recession growth recovers after 2027.

The contradiction in today’s market: traders worry about 2026 oversupply, while supply capacity growth will contract after 2029. Major national oil companies illustrate the scale of capital required: Saudi Aramco increased its upstream spending by 19% to $39 billion in 2024, while Abu Dhabi’s ADNOC plans to spend $150 billion between 2024 and 2027 to achieve a crude supply capacity target of 5 million barrels per day by 2027, according to IEA data.

The timing of capacity constraints—supply growth peaking around 2027 before contracting after 2029—gives the industry a narrow window to address investment deficits before structural shortages emerge.

The oil market’s hidden crisis isn’t about today’s balance sheets—it’s about the supply capacity that won’t exist in 2029 because of investment decisions not made in 2024. Russia’s sanctions-induced collapse is bringing that reckoning closer.