Ukrainian farmers navigate minefields and missile strikes, but they do so with GPS autopilots, AI yield forecasts, and satellite monitoring systems.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in November that Ukraine’s food exports feed 400 million people in 100 countries, much of it in the Middle East and North Africa, where alternatives to its grain don’t exist at scale.

As Russia bombs ports and rails to strangle these exports, Ukrainian producers are making a different bet: precision agriculture that squeezes more yield from every hectare and gets it to market faster.

Striking scale

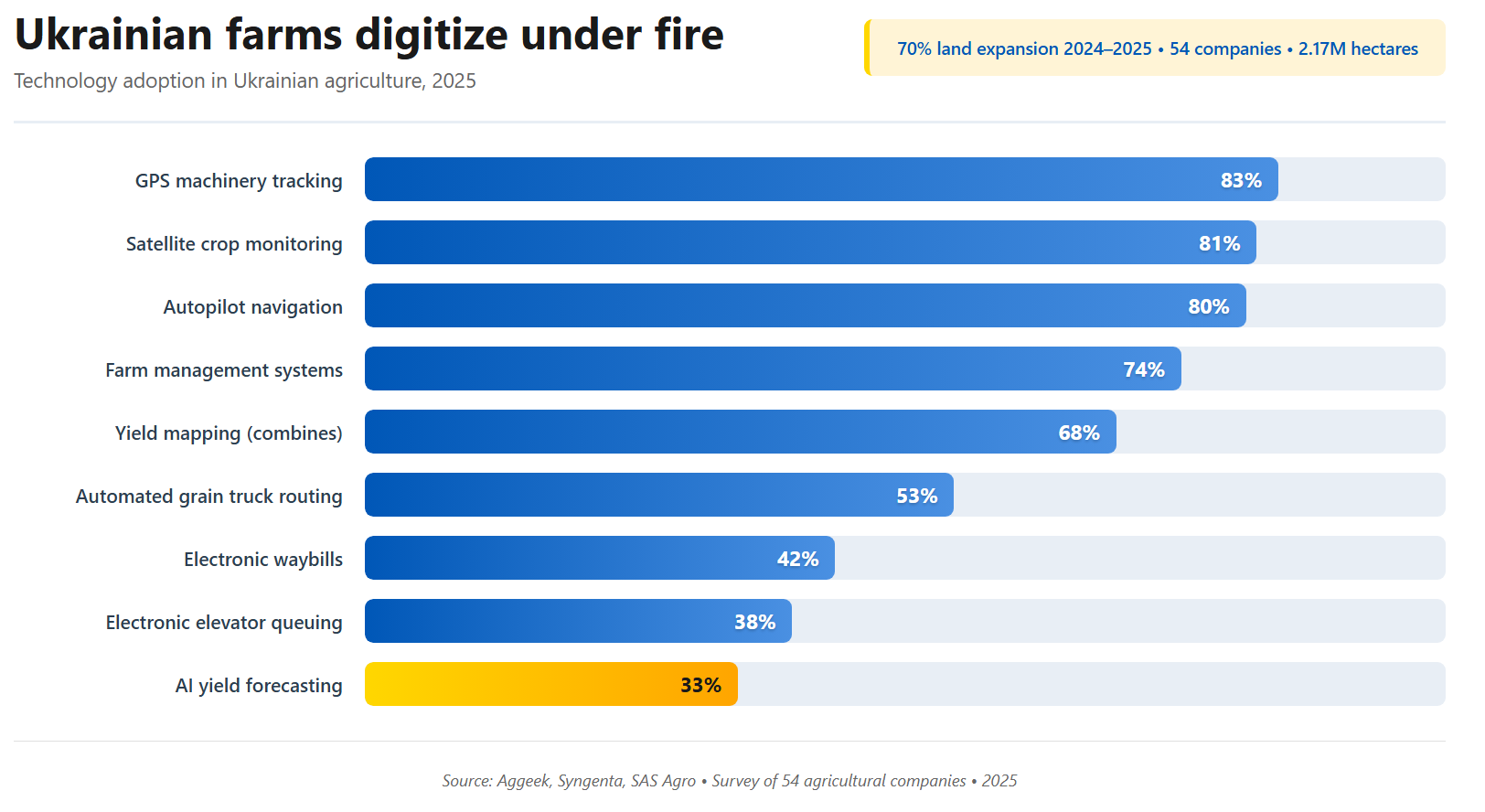

The scale of adoption is striking. Eighty-three percent of Ukrainian farms now track their machinery with GPS, 80% use autopilot navigation, and 81% monitor crop development through satellite imagery.

Three in ten farms deploy AI to forecast yields. Seventy-four percent run specialized software to coordinate field operations—planting, spraying, harvest—across hundreds or thousands of hectares.

The 54 agricultural companies surveyed for this report manage 2.17 million hectares—roughly 10% of Ukraine’s farmland still in production. That’s 70% more land than the same group farmed a year ago. During a full-scale invasion, Ukrainian producers didn’t retreat. They expanded from 80-hectare operations to Ukraine’s largest oil producer, Kernel’s 500,000-hectare empire, and digitized.

Some of these farms are adjacent to active combat in Sumy and Kherson oblasts. They use the same satellite imagery systems to spot crop stress and avoid freshly mined areas.

Tech that binds

The technology chains together. Sixty-eight percent use yield mapping in combines, feeding data into next year’s variable-rate seeding plans. Fifty-three percent automate grain truck routes from field to elevator.

Forty-two percent eliminated paper waybills, and 38% use electronic queues at delivery points—no drivers idling for hours while Russia launches missiles at grain infrastructure.

Trending Now

The findings come from Aggeek, a Ukrainian agtech consultancy working with Syngenta—one of the world’s largest agricultural input companies—and SAS Agro, a Ukrainian agricultural systems provider.

In addition to the 54 companies that filled out detailed surveys, another 2,220 producers answered shorter questionnaires about specific technologies. Participation was anonymous; results show aggregated patterns, not individual company data.

The only way is up

The obstacles are what one would expect during an invasion: 65% cite equipment costs as the main barrier, 61% point to expensive inputs, and 57% to labor shortages. Forty-three percent say export prices and logistics are the problem. Thirty-five percent note that military operations disrupt their territory.

But the digitization continues anyway.

Russia wants to wreck Ukraine’s economy through bombardment. Ukrainian producers are building the infrastructure to do the opposite—feed more people with fewer inputs, using farmers’ phones and satellites instead of more land and diesel.