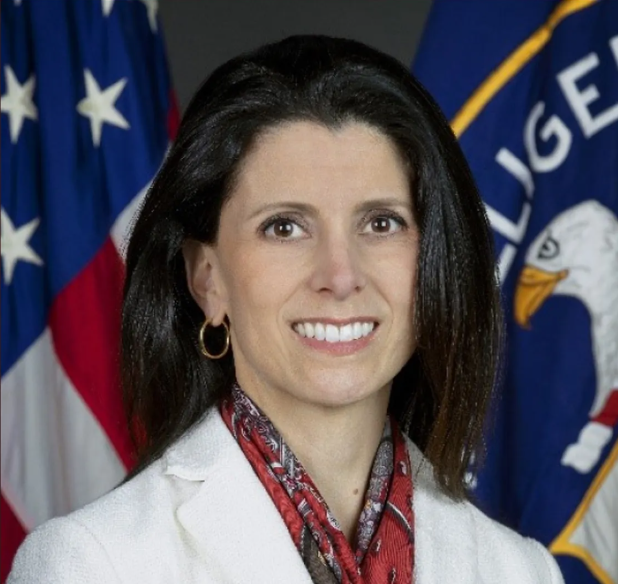

When the story broke on 25 April, it stunned the world: Michael Gloss, the 21-year-old son of CIA Deputy Director Juliane Gallina Gloss, had joined the Russian army—and was now dead on a Ukrainian battlefield.

Here was a national security family's son, once full of idealism, who had studied human ecology and dreamed of bringing clean water to communities in need. Yet just eight months in Russia had turned him into a soldier in Putin's war—against the Ukrainian people his American government was supporting.

Friends described Michael as seething with anger toward America, viewing "violence as an integral part of the US political system." One said his primary goal was to "fight against America," while another believed he sought faster Russian citizenship.

The timeline was chilling: His visa expiring on 5 September 2023. Appearing that very same day at a Moscow recruitment center. By April 2024: dead near Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine.

His father, Navy veteran Larry Gloss, could only explain his son's metamorphosis through mental illness, describing Michael as "the ultimate antiestablishment, anti-authority young man."

The story was first published by the Russian independent outlet Important Stories (Vazhnyie istorii), where Egor Feoktistov works as an investigative journalist. Like many of his colleagues, though not all, Feoktistov now lives in Europe, continuing his work from exile.

Euromaidan Press spoke with Feoktistov to understand how Russia's military recruited the son of America's top spy—and what this reveals about their broader war machine. We explored Michael's radicalization, the massive security lapses in Russian recruitment, the scale of foreign mercenary enlistment, and the findings of IStories on Russian war crimes.

Editorial note: The interview has been edited for clarity.

How a leaked database led to a shocking discovery

EP: How did you find out about the death of Michael Gloss?

EF: We discovered a data leak revealing about 1,500 foreign mercenaries who enlisted through a Moscow recruitment center. Multiple foreigners shared this same address in a Russian government database.

Among the names was Michael, with minimal online presence except a November 2024 bibliography. This document revealed that Michael is the son of Gallina Gloss, CIA Deputy Director for Digital Innovation, and Larry Gloss, a US Navy veteran, who participated in Operation Desert Storm [the 1991 US-led military operation against Iraq - ed.].

Connecting the dots: tracing Michael Gloss’s path to War

EP: What was your purpose for searching the names of these people?

EF: We wanted to prove that this database contains at least dozens of verified fighters and prove that these individuals did join the Russian army.

We discovered up to 200 names that were publicly available and known for their participation in the war.

EP: Was it the first enlistment of foreigners in the Russian army?

EF: Some foreigners joined earlier through different channels, with several appearing in a deserters' database.

I found several foreigners' names in this base. By 2022, at least two dozen were fighting for forces in Donetsk, Ukraine.

When Putin declared Russia would welcome foreigners and offer citizenship, some had already been joining since the full-scale invasion began. However, the numbers weren't significant until this recent discovery.

EP: Did you search every name in the leaked database? What made Michael Gloss stand out?

EF: No. We didn't know the fate of the hundreds of mercenaries we discovered, though many are still alive.

We searched for media stories about them, like a Nepali man mentioned by CNN or an Indian who committed suicide.

Michael was just one name on the list.

We only had his name and birth date from his recruitment center visit, and we had no information about his citizenship or potential US connection.

What his friends really thought

EP: How did you track down Michael's Turkish and Russian friends?

EF: Michael's obituary described him as part of the Rainbow Family community [a counterculture movement inspired by Woodstock - ed.]. I searched Rainbow Family group chats and found his Telegram account, which led to additional chats he participated in. Through these conversations, we identified his contacts.

In October 2024, a friend announced Michael's death in these chats. People shared memories about him, including one close friend who posted a message explaining Michael's motivation. We simply connected publicly available information from open chats with conversations from people who knew him.

EP: How did Michael's friends feel about his decision to join the Russian army?

EF: Many were surprised, but I wouldn't say there was any condemnation among them. They seemed to prefer avoiding discussing this outcome of his life.

A significant number of his friends either shared his views or remained neutral about his choices.

Only one person expressed doubt, which, in the end, led to heated arguments about whether one can speak about the dead like that or not.

EP: Michael condemned American violence while joining an invading army himself. How do you view this contradiction between his words and actions?

EF: I think it works the same way as it does with people in Russia who support Putin. They selectively filter information, finding convenient explanations for anything contradicting their views.

By the time Michael arrived in Russia, his views were quite radical. His posts showed his deep disillusionment with the American system. He disliked both Democrats and Republicans and society's structure generally. He sought escape and a completely different social organization, somehow idealizing Russia despite never visiting and likely knowing little about it.

He couldn't accurately assess how much reality matched the image he'd formed far away in the States.

As his fellow serviceman later noted, Michael didn't understand what real Russia is actually like.

Inside the CIA connection—and what Michael’s parents knew

EP: Did his parents know whether he joined the Russian army?

In one of the comments, his father said that they found out through his geolocation that he was in Avangard, Moscow Oblast.

When questioned, Michael dismissed it as "nothing serious," though his explanation remains unclear. [Avangard, located in Moscow Oblast, is home to a major military-patriotic training center operated by the Russian Ministry of Defense. Its presence suggests possible involvement in recruitment - ed.]

His parents may have suspected he was undergoing military training, but it's unknown how much they realized about his army involvement or what actions they took.

Michael stopped communicating with his family in March 2024 and died on 4 April. They only learned of his death in June 2024.

EP: How did Russia recruit the son of America's top spy? With his parents' high-ranking positions in intelligence, military, and cybersecurity - and his ability to maintain contact during combat - was this an oversight or did they simply not check his background?

EF: We know that these foreigners underwent some checks. Strangely enough, no one reportedly did checks on family connections.

While these foreigners underwent some checks, no one reportedly verified family connections. This reveals significant negligencу in the Russian army.

Even more strange, he wasn't interrogated when obtaining a Russian visa or at border control, as frequently happens with many travelers to Russia.

For days, he walked around Red Square in unusual attire without attracting attention or being questioned.

How Russian military vetting failed to spot a spy’s son

EP: So this was likely an oversight in Russia's recruitment vetting. Has the Russian military responded to your story? Did they take any action? What was the reaction in Europe and America?

Trending Now

EF: This is typical Russian bureaucracy. Punishment for those who missed him may be delayed. It represents a failure of military counterintelligence and recruitment personnel.

Foreigners typically complete detailed questionnaires, including family information, making this a systemic failure at all levels. Consequences may occur, but either won't be public or will happen months later.

It's particularly strange that the CIA claims there are no national security concerns.

Perhaps they're reluctant to admit their own failure - that they have no control over or awareness of family members of intelligence officials who could end up in Russia. Apparently, they have no control over them, but it could have created a significant situation.

The journalist’s estimate: How many foreigners fight for Russia?

EP: How many foreigners are fighting for Russia? Do you have both official figures and leaked data?

EF: Approximately 1,500 people pass through the Moscow recruitment center alone each year.

Recruitment also occurs in regional centers, attracting citizens from neighboring countries seeking employment. The project I Want to Live counted up to 1,000 foreign recruits, including citizens of the Baltic states. [I Want to Live is a Ukrainian state project which helps Russian servicemen safely surrender to Ukrainian captivity and save their lives - ed.]

I would estimate the total number of foreigners in the Russian army at roughly 10,000-15,000.

The majority likely come from Belarus, Tajikistan, and similar countries. China probably contributes several hundred recruits, but they're unlikely to be the largest nationality represented. This doesn't include North Koreans, who don't yet appear in any statistics or personal lists we can access.

We've identified nearly three dozen people from a wide range of European countries, though usually just a few individuals from each nation. We found people with Austrian, Italian, and French citizenship, and one person from Great Britain. The majority come from Balkan countries. So far, we've confirmed eight Serbian nationals.

EP: In your opinion, what motivates these foreign fighters? Is it primarily a financial incentive?

EF: I believe there are two primary levels of motivation:

First is sympathy for Russia - a general support and approval of Russia's policies. In Nepal, for example, there's evident public support - people view TikTok videos posted by Nepalese fighters, actively support their decision to join the Russian military, wish them luck, and view these volunteers as heroes.

The second motive is financial compensation. If someone is primarily motivated by money but knows their choice wouldn't be approved in their home country, or if their country doesn't have a positive attitude toward Russia, they would likely reconsider.

That's why most foreign fighters come from countries that generally support Russia's policies and approve of Russia's actions.

EP: You've uncovered significant failures even within Russia's elite military units. Given these problems, how realistic are Russia's threats to NATO countries, especially along the Baltic borders where they're increasing forces?

EF: I am sceptical about Russia's ability to fight NATO. However, the outcome would depend on the nature of the conflict. If Putin believes hostilities could be limited to a small territory of one or two countries without triggering a full NATO response, they might have sufficient forces.

This scenario might be realistic if Russia were fighting against the small army of one or two minor countries without actual support from other NATO members. Then it simply becomes a question of how many additional resources and personnel Putin could redirect from other areas to support such conflicts.

I'm concerned that NATO assistance might arrive too late.

Based on Ukraine's experience, Russia understands how to gain short-term advantages within approximately one week of action.

This delayed assistance may fail to prevent significant casualties. I don't yet see clear plans for countering even the small advantages Russia could gain through surprise attacks, large concentration of forces, and the delayed NATO response.

Russia's war crimes in Ukraine

EP: What do you know about the Russian torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians? What's your view on cases like journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna's murder?

EF: I think this is a logical extension of Putinism as a system in which cruelty has been normalized. People who violated the law and tortured others in Russian prisons have historically not faced proper punishment.

This system of torture within Russian prisons, colonies, and detention centers remained unchanged by 2022, and has since become even more ferocious and harsh.

This represents a fundamental attribute of the entire system that cannot be addressed without completely dismantling it. There are likely many more such cases than have been documented. For the perpetrators, it's even easier to commit these acts against Ukrainians, toward whom they have no pity.

Moving forward, there's an opportunity to identify the individuals involved and begin work on their prosecution, making their actions known to the public.

Addressing the entire system of prison torture would require thousands of criminal investigations to process everything that has accumulated over many years.

EP: In your view, should Russia undergo a process similar to Germany after World War II - with trials for war crimes and a national reckoning? Is this even discussed among Russian journalists?

EF: This discussion exists, but we face challenging realities. The United States doesn't support the ICC and ignores its decisions. Even European unity appears somewhat fragile.

The ideas prevalent in Russian opposition and journalistic circles - that trials would eventually happen and those responsible might be convicted - now seem increasingly distant. Speaking personally, these hopes are evaporating, and I'm less certain about the likelihood of such accountability.

Currently, no established mechanisms exist to conduct these trials and determine guilt. There's no consensus among countries to pursue them quickly. However, I see Europe's approach accelerating compared to their concerns from a year or two ago.

The accountability must extend beyond just Putin and a dozen generals.

I believe around 1,000 people directly involved in ordering and executing war crimes should face justice - though this will likely happen much later than we'd hope.

EP: What needs to happen in Russia for it to move beyond this war?

EF: Russia cannot have a normal future without a just resolution to this war.

There's significant risk the current regime will persist for decades, and it seems impossible for Russia and its people to live peacefully - both domestically and internationally - without accepting Ukraine's legitimate security demands.

I would prefer something similar to Germany's post-war transformation. Without establishing at the state level that this was a criminal war deserving condemnation, those who quietly supported it will simply undergo superficial changes while continuing their lives as before.

Some perspectives might genuinely change once accurate information becomes widely available and public analysis exposes the propaganda that dominated Russian media.

This reckoning process must begin, or Russia will continue threatening its neighbors and the international community even after Putin.

What would a just resolution to the war look like?

EP: What would you consider a fair end to the war?

EF: Simply returning territory wouldn't solve the underlying problem. Even if Ukraine regained Luhansk and Donetsk with Crimea remaining disputed, many Russians would still believe they have legitimate claims to Ukrainian land.

The dangerous narrative would persist in Russia even after Putin: "Here we succeeded, here we failed, but we need to finish this."

Without completely reassessing everything since 2014, or even earlier regarding Russia's involvement in Ukrainian politics, lasting peace isn't possible. The issue would inevitably resurface within 5 to 20 years, with someone following Putin's precedent.

Many Russians may again seek that same unchecked power—an easy path to reconsolidate society and start a new war.