In February of 1945, as World War II entered its final chapters, three men gathered in a war-ravaged palace on the Crimean coast to reshape the world. The Yalta Conference brought together the titans of their age – Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin – in what would become one of history's most controversial summits.

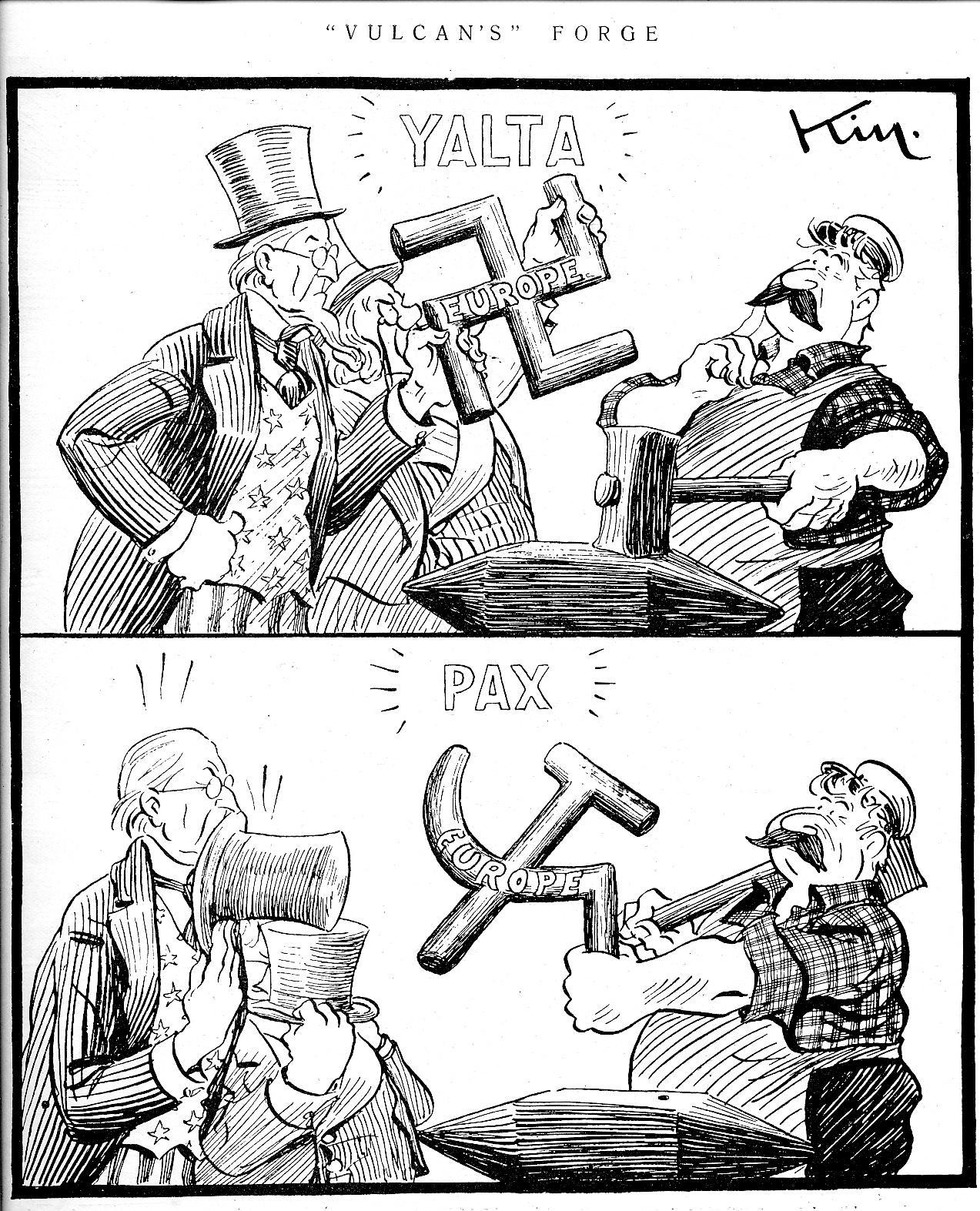

Sandwiched between the Tehran and Potsdam conferences, the Yalta meeting spawned the United Nations and laid the groundwork for the post-war global order. However, while those talks became synonymous with WW2's conclusion in public memory, their outcomes proved far more problematic than promising. Within a week, the conference's ambitious peace agenda devolved into a Western appeasement of the Kremlin – a concession that would undermine the very security it sought to ensure.

Not coincidentally, for decades that followed, the Kremlin rhethoric has wielded Yalta as the ultimate symbol of its geopolitical influence — a precedent Putin desperately seeks to recreate, hoping the West might once again agree to partition the world, repeating the catastrophic miscalculations it made eight decades ago.

The meeting that defined the 20th century

The Yalta Conference unfolded at a pivotal moment in WWII – in the wake of D-Day's liberation of France and Belgium, as Nazi forces retreated from Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria. With Soviet troops positioned just 65 kilometers from Berlin and Allied forces advancing through Germany's western border, Hitler's defeat appeared inevitable.

Roosevelt, who initially proposed the conference to solidify his vision of a liberal post-war order before the 1944 US elections, saw it as crucial for determining Nazi Germany's fate after Hitler's imminent fall. After Stalin rejected multiple venue proposals, the Big Three ultimately convened in Yalta a year after it was first proposed.

The conference's setting was grimly symbolic: a devastated Crimean city where only a few hundred residents remained after Nazi occupation, brutal Soviet reconquest, and Stalin's deportation of over 400,000 indigenous Crimean Tatars – a crime that killed nearly half of the nation.

In this environment, ailing Roosevelt – who risked his health on the lengthy journey to the USSR – and Churchill, intent on checking Stalin's expansion into Western Europe, gathered to shape both the war's conclusion under the watchful gaze of the Soviet surveillance who planted listening devices throughout the guest quarters and even park avenues, feeding their Kremlin host intelligence about their growing rifts.

On 5 February 1945 – the day after the high-profile guests arrived at war-shattered Tsarist properties in Crimea, hastily furnished by Stalin’s orders – the three world leaders raced to secure their vital interests. Stalin pushed for reparations from Germany, Roosevelt sought Soviet support for the war against Japan and help in starting the UN, while Churchill zeroed in on Poland, whose Nazi occupation had drawn Britain into the war.

The partnership that split the world

The "Big Three" carved up postwar Germany into American, British, and Soviet zones, with Berlin split along the same lines. As Britain lost its imperial grip, it set its sights on France as a crucial continental ally it now desperately needed to counter Germany. To boost Paris’ geopolitical wage, Western leaders sought to create the French occupation zone in Germany, a move Stalin accepted — though only at the cost of British and American gains.

However, the agreement on Germany’s future was where the consensus among the three leaders ended.

The most contentious issue at the conference was the future of Poland — the first country occupied by the Nazis — with eight plenary sessions devoted to it. For Churchill, the Polish question was especially urgent, as he sought to secure Britain's influence zone in Europe, including Greece, Hungary, the Balkans, and Poland — whose exiled government Britain now hosted — anticipating the decline of its colonial might.

However, Stalin had his own designs on Poland — and they were a driving force behind the outbreak of World War II. In August 1939, the Kremlin secretly struck a deal with Hitler in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, agreeing to divide Poland and setting the stage for war just weeks later. By mid-September, the USSR invaded Poland, justifying the occupation of its eastern territories as a move to "protect" local Ukrainian and Belarusian populations — whose lands were already under Soviet control — from the Nazi threat.

At Yalta, Stalin pushed to redraw Poland’s borders against Churchill’s wishes, citing security concerns after Germany used Poland as an invasion corridor in both world wars. Under Stalin's pressure, the USSR— specifically Soviet Ukraine and Belarus—was granted the eastern territories of Poland along the Curzon Line, a 1919 British proposal to resolve disputes between the USSR and Poland. Meanwhile, Poland’s western borders were shifted westward, absorbing German territories.

To justify his territorial claims, Stalin strategically used the self-determination factor, positioning the landgrab as essential for safeguarding ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians. This left his Western counterparts in a bind, as they had championed the right to self-determination in their vision of a post-war free world.

The Kremlin insisted that incorporating these eastern territories, home to large Ukrainian and Belarusian populations, was crucial to creating a homeland for these ethnic groups within the USSR.

“At Yalta, it was necessary to legitimize these new territories, to prove that they truly belonged to the Soviet Union,” says Serhii Plokhy, director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University. “For Churchill and Roosevelt, it was a legitimate argument — they understood the idea of creating a common political space for one nation.”

Later, Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff to Franklin Roosevelt, criticized the Polish solution, saying, “This [agreement on Poland] is so elastic that the Russians can stretch it all the way from Yalta to Washington without ever technically breaking it.”

But redrawing the map of Poland was just the beginning – the real issue was who would govern the country.

As the Red Army advanced through Poland, Stalin set up the puppet Lublin Committee, rejecting Churchill’s plea to restore the exiled democratic government that had fled to Britain. Churchill pushed for free elections, but Stalin argued the exiled leaders had been absent during Poland’s liberation, unlike the Lublin Committee.

In the end, Churchill backed down, and the three leaders agreed to “broaden” the Soviet-backed puppet administration, adding democratic leaders from within and outside the country and tasking it with holding elections as soon as possible.

Within months of the negotiations, Stanisław Mikolajczyk, head of the exiled Polish government who had relied on British aid and had been effectively displaced by the Soviet-backed committee a year earlier, was pressured by Churchill’s cabinet to accept the new borders and the Kremlin-installed authority.

The Soviet-backed Polish government, legalized by the Big Three, held the promised elections only two years later. Rigged to cement Communist rule, they were condemned by both the UK and the US. Powerless and stripped of power, Mikolajczyk had to emigrate once again – this time, for the rest of his life – to save his life from looming communist purges.

In just one week of negotiations, Poland — the first independent nation to fall victim to the Nazis and the West’s trusted ally in the fight against the Nazi regime from the first day of World War II — was effectively sacrificed by the West as a Soviet buffer zone, paving the way for the Kremlin's further expansion.

“Yalta became a symbol of betrayal — the betrayal of Poland, Eastern Europe, and the smaller nations of the world. So, right after the fall of the Soviet Union, those countries that considered themselves "occupied states" freed themselves,” Plokhy told Radio Liberty.

Agreements can betray nations. Free press defends them.

For 11 years, Euromaidan Press has been reporting Ukraine's fight for freedom — because autocrats are already plotting yours.

Stop reading history. Create it — become our patron now.

The ticking bomb under the rules-based order

While Churchill's gaze was fixed on Europe’s future, Roosevelt’s ambitions were global. Like Wilson’s “14 Points,” his goal wasn’t just alliances but a complete overhaul of the global order. In August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill released the Atlantic Charter, a blueprint for a post-war world built on the freedom of nations to self-determine, open trade, and global security through founding the United Nations.

Yet, bringing Roosevelt’s brainchild to life hinged on Stalin’s approval – and for that, the Kremlin demanded to grant the USSR a veto power in the UN Security Council and set for each of its 16 republics. By the time the Yalta talks kicked off, the Western allies managed to curb Stalin’s appetites for disproportionate Soviet representation in the UN to including Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania — a Baltic nation occupied by the USSR in 1940 under deceptive circumstances.

Roosevelt’s ambition to bring Stalin into his proposed rules-based order, outlined in the Atlantic Charter, collided with the bitter legacy of Wilsonian isolationism. This policy had already cost the US the influence it could have used to check Stalin’s growing ambitions — ambitions bolstered by the Soviet Army, which had occupied a third of Europe in its march against the Nazis.

Wilson’s “America First” rhetoric, rooted in the belief that Europe had tricked the US into World War I, led to a withdrawal from European affairs, leaving Britain and France — already weakened by WWI — to confront Hitler and Stalin alone. This resulted in Hitler’s rapid conquest of the continent.

By the time the United States entered WWII in December 1941, it had no choice but to rely on Stalin to defeat Hitler, and with no exit strategy, Roosevelt found himself catering to Moscow’s ambitions to shape the post-war order. He believed Congress would never allow him to maintain US forces in Europe for more than two years, making the USSR an indispensable ally.

The Western allies ultimately gave in to Stalin’s demands for disproportionate Soviet representation in the UN, agreeing to make Ukraine and Belarus separate founding members while leaving Lithuania out due to disapproval of Stalin's expansionist actions in the Baltics.

Roosevelt also managed to secure Stalin’s consent to the Declaration of Liberated Europe, which aimed to apply the principles of the Atlantic Charter to nations freed from Nazi occupation. The declaration highlighted the right to self-determination, especially for Poland — an issue crucial to Britain, as it had been the catalyst for the UK's declaration of war on Germany in 1939.

Additionally, the leaders agreed to grant veto power to all permanent Security Council members, with Stalin securing a veto for both the USSR and its ally China. This move weakened the UN from the outset. In the years that followed, the USSR and Russia used the veto 120 times — almost half of all vetoes in UN history — with Moscow blocking 86% of resolutions vetoed after its 2014 invasion of Ukraine.

The West’s Faustian bargain with the Kremlin

While Germany's defeat was imminent, Japan's surrender was far from certain, driving Roosevelt to seek Stalin’s support at any cost. In an effort to secure Stalin’s agreement to enter the war against Japan — something he pledged to do only three months after Germany's surrender — Roosevelt offered significant concessions, inclusing Japanese territories Russia had lost in the 1905 war, leasing strategic Chinese ports to the Soviets, and pushing for the independence of Mongolia, at the time a Soviet satellite under Chinese control.

The concessions came despite British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden's warning that Stalin had intrinsic interests in the region and would join the war against Japan:

"If the Russians decided to enter the war against Japan they would take the decision because they considered it in their interests that the Japanese war should not be successfully finished by the U. S. and Great Britain alone. There was, therefore, no need for us to offer a high price for their participation,” Eden said.

History proved Eden’s warning correct. In April 1945, just two months after making concessions at Yalta to secure Stalin's commitment against Japan, Roosevelt died from a massive brain hemorrhage. In July of that year, his successor, Truman, tested the atomic bomb a day before the Potsdam Conference — the final summit of the Big Three that locked in the new world order.

At the conference, the Allies issued an ultimatum to Japan, with Truman authorizing the use of nuclear weapons if Japan refused to surrender. Just a week after the Postdam negotiations were over, two nuclear strikes carried out by the Truman administration brought Japan to its knees, rendering Roosevelt’s costly deal with Stalin a moot point.

The peace deal that sparked the Cold War

Only two weeks after Yalta, Roosevelt addressed Congress, resolute in his belief in lasting peace:

"Never before have the major allies been more closely united — not only in their war aims but also in their peace aims. And they are determined to continue to be united, to be united with each other – and with all peace-loving nations — so that the ideal of lasting peace will become a reality."

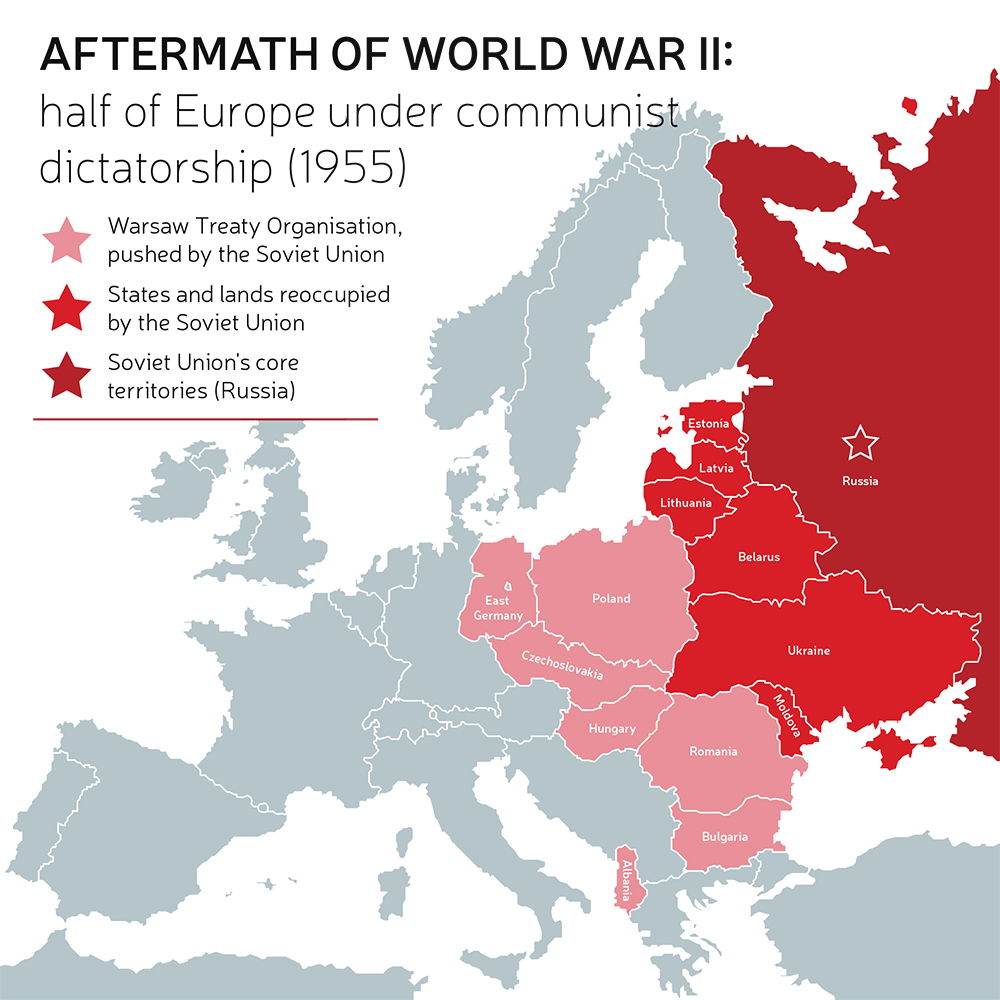

However, Western optimism, unlike the concessions made to the Kremlin, quickly soured. Even before Germany's surrender, the Soviet Union had already broken its promises, installing a communist regime in Poland and taking full control of Romania.

Just two weeks after his rallying speech to Congress, Roosevelt sent a sharp telegram to Stalin, expressing his alarm over the betrayal of the Polish deal. Two weeks later, Roosevelt died, leaving Truman to pick up the pieces.

On May 12, 1945 — just four days after Germany’s long-awaited capitulation, the very cornerstone of the Yalta deal — an alarmed Churchill telegraphed Truman about Stalin's breach of the negotiations, stating:

"An iron curtain has come down. We do not know what the Russians are doing in the areas they control. They control large areas of Central and Eastern Europe, and their control is growing."

A year later, Churchill would publicly echo this warning in his famous Fulton speech, with the "Iron Curtain" becoming a defining metaphor of an era that would polarize the world for the next five decades.

At nearly the same time, US chargé d'affaires in Moscow, George Kennan, sent a cable warning that the Soviet Union sought to expand its sphere of influence and weaken the power and authority of Western nations.

By March 1947, the US enacted the Truman Doctrine, officially outlining the strategy of containment against communist regimes — marking the official start of the Cold War.

The promises of Yalta crumbled before they had even begun to take shape.

The playbook behind Putin’s world carve-up

Under Putin’s rule, the collapse of the Soviet Union has repeatedly been dubbed the “largest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century,” and the Yalta Conference resurfaced in the Kremlin’s messaging.

The push for a “new Yalta” came to the forefront after Putin’s 2007 “Munich speech,” in which he declared that “the entire legal system of a single state — primarily, of course, the United States — has overstepped its national borders in all areas: the economy, politics, and the humanitarian sphere, imposing itself on other nations.”

The shift gained momentum in 2008, when Russia launched hybrid warfare to block Georgia’s and Ukraine’s NATO ambitions, followed by the invasion and partial occupation of Georgia — an act largely ignored by the West.

Following Russia's 2014 invasion of Ukraine, Putin became more vocal about his desire for a "new Yalta." The Kremlin's underlying aim — to carve up spheres of influence at the expense of now-sovereign post-Soviet nations — has repeatedly resurfaced in Russian media and public communications, with Russia openly signaling his intentions to the West.

In September 2015, a year and a half into his war against Ukraine and fresh off Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, Putin took the stage at the UN General Assembly to declare his Cold War-style ambition. He stated that “key decisions on the principles defining interaction between states, as well as the decision to establish the UN, were made in our country, at the Yalta Conference”, a brazen nod to the Crimean city Russia had seized in 2014.

In this speech, Putin once again blamed NATO’s so-called expansion for his war on Ukraine, using Yalta as a pretext to push for a new carve-up of Europe, where “neutral” buffer states would shield Russia’s sphere of influence.

The next time Putin revived the Yalta argument in 2020, in an article published in The National Interest — a US neoconservative magazine run by Soviet-born Dmitry Simes, a Kremlin-friendly pundit with ties to Russian state media.

Building on Russia’s longstanding WWII narrative — where the USSR is credited with doing the heavy lifting against Nazi Germany while Stalin’s 1939 pact with Hitler is downplayed — Putin shifted blame for it onto the West, even implicating Poland, the war’s first invaded nation. Toward the end, he floated the idea of a new "Yalta Conference," calling on the UN Security Council’s permanent members — Russia, the US, the UK, France, and China — to redraw the global order.

Viktor Shlinchak, Chairman of the Board of the Institute of World Policy, argues that Putin’s ultimate goal in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine is a “new Yalta” — a bid to resurrect Russia’s superpower status by striking a grand bargain with the US at the expense of sovereign nations that broke free from the USSR.

“Putin wants a new Yalta, where he can sit down with Trump and strike a deal giving him the right to boss around these "petty Europeans,” Shlinchak says.

In turn, Serhii Plokhy, argues that the greater lesson of Yalta — often remembered as the “second Munich” — lies in the dangers of compromising the very principle the West aimed to uphold during those talks: the inviolability of state sovereignty.

“A great lesson is that two or three countries coming together and agreeing among themselves cannot determine the future of the entire world,” Plokhy says. “This is the key lesson of Yalta that world leaders should have learned, though I'm not sure they have.”