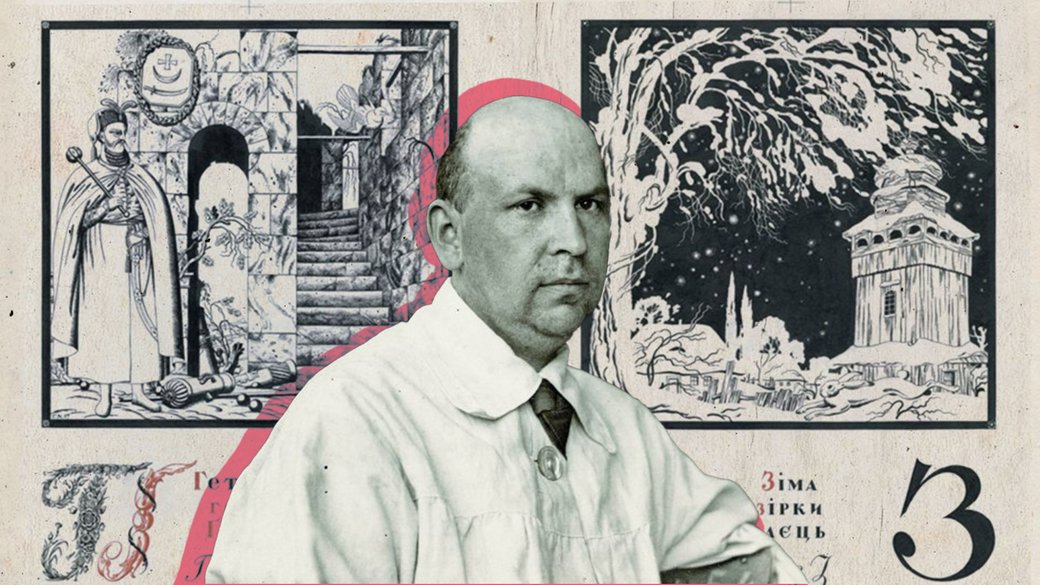

A controversy has emerged surrounding the legacy of Heorhii Narbut, a celebrated Ukrainian graphic artist and considered the father of Ukrainian typography.

Russian designer Aleksander Shimanov’s portrayal of Narbut as a “great Russian artist” has drawn widespread criticism from the Ukrainian community, with accusations of cultural appropriation and colonialism.

In fact, Shimanov created a typeface called ST-Surzhik, claiming it was inspired by Heorhii Narbut’s work. Shimanov has publicized it widely on his Instagram page.

Alexander Shimanov, a graphic and web designer from Nizhny, Novgorod, Russian Federation, is known for his fascination with Soviet-era aesthetics, including fonts inspired by propaganda posters.

His latest creation, the ST-Surzhik font, derives its name from “surzhyk.” Surzhyk in itself is more than a simple mix of Ukrainian and Russian as it includes several varied phenomena.

On his social media, Shimanov describes the typeface as a “fictional Old Rus font blending various stylistic forms.”

He goes on to explain that Narbut’s work from his St. Petersburg period reflects the influence of classical Russian typefaces, including elements of the early Petrine civil script (part of Tsar Peter I's reforms). The design also incorporates features from the rounded Bulgarian Glagolitic script, interwoven with Art Nouveau stylistic elements.

Actually, Shimanov acknowledges that Narbut is the father of Ukrainian typography but claims that Narbut’s lettering has Russian origins. He adds that “without Narbut, Ukrainian typography as a distinct entity, separate from the broader Russian typographic tradition, would disappear in a flash.”

Heorhii Narbut, born in 1886 in Ukraine’s Chernihiv Oblast, was a groundbreaking graphic artist whose work laid the foundation for Ukraine’s modern visual identity.

His early fascination with heraldry and Ukrainian motifs evolved into a distinctive artistic style that merged European trends with Ukrainian themes. Narbut’s legacy includes the creation of Ukraine’s first state symbols, such as the coat of arms, banknotes, official seals, and postage stamps, designed for the newly-founded Ukrainian People's Republic. His most celebrated work, the Ukrainian alphabet, published in 1917, intricately combined baroque ornaments, mythological imagery, and elements of Ukrainian folk culture.

But Shimanov says Narbut’s legacy should not be handed over exclusively to Ukrainian nationalists, downplaying the significance of Narbut’s contributions during his time in Kyiv.

According to Shimanov, Narbut “grew up within the Russian cultural code, absorbed Russian classics, and ultimately became a Ukrainian nationalist towards the end of his life.” He argues that Narbut’s Kyiv heritage is far less significant than his work in St. Petersburg.

The Russian designer underlines that the ST-Surzhik font supports several languages, including Russian, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Chuvash, Tatar, Mari, Bashkir, Udmurtian, English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Croatian, Finnish, Slovenian - but notably excludes Ukrainian. Critics argue that this exclusion is emblematic of a broader effort to undermine Ukrainian identity and achievements.

Heorhii Narbut’s artistic journey took him from Hlukhiv in Ukraine to St. Petersburg, where he studied and collaborated with Russian artists. During the Russian Empire and Soviet periods, it was customary - and almost inevitable - for Ukrainian intellectuals to study in Moscow or St. Petersburg, as these cities offered the only path to gaining recognition and advancing their careers.

Despite gaining honor and esteem during his time in Russia, Narbut’s return to Kyiv in 1917 marked a turning point. He became a professor of graphics and later the rector of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts, transforming his Kyiv apartment into a hub for artists and intellectuals. His work during this period profoundly shaped Ukrainian cultural identity.

Narbut’s life was tragically cut short by illness in 1920 at the age of 34. However, his contributions to Ukrainian art and national identity remain significant. Ukrainian historians and cultural commentators emphasize that Narbut “graphically ‘Ukrainized’ ” Ukrainian culture, embedding its unique character into his designs.

In the meantime, Ukrainian analysts and media outlets have criticized Shimanov’s claims, framing them as part of a larger pattern of Russian cultural appropriation. The independent information campaign on media literacy, fact-checking, and the development of critical thinking Po toi bіk novyn (Behind the News) argues that such narratives aim to deny Ukrainians their distinct identity.

“The claim that Narbut’s Kyiv period is less important than his activities in St. Petersburg exemplifies an effort to downplay Ukrainian achievements,” says Aliona Malichenko with Behind the News.

Specialists in typography and cultural heritage have highlighted the significance of typography and fonts as tools of cultural influence. Typography is a powerful expression of cultural identity, serving as a visual representation of a community’s heritage, values, and aspirations.

“Appropriating Ukrainian cultural heritage, as in the case of Heorhii Narbut, and using Russian fonts in the public space, are tools of ‘visual occupation’ that undermine Ukrainian identity,” Malichenko says.

Heorhii Narbut’s legacy as a pioneer of Ukrainian typography stands in stark contrast to Russia’s attempts to redefine his work within a Russian context. In respect of the ongoing war and as Ukraine continues to assert its cultural independence, the debate over Narbut’s heritage underscores the broader struggle for recognition and preservation of Ukrainian identity in the face of ongoing cultural and political challenges.

RELATED:

- Recovering the forgotten names of the Ukrainian avant-garde

- “Pushing Hollywood aside” – renaissance in Ukrainian cinema

- New documentary on Crimean occupation released | VIDEO

- “Man with a Movie Camera”: One day of a 1920’s Ukrainian city in the early Soviet times

- Meet Ukraїner, “project that tells the world about the least discovered country in Europe”

- Eleven films about Euromaidan you can watch online

- New film shows Kazakhs they suffered a Holodomor too, infuriating Moscow

- The Hunger for Truth: Documentary about Canadian journalist who was first to report about Holodomor

- Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas