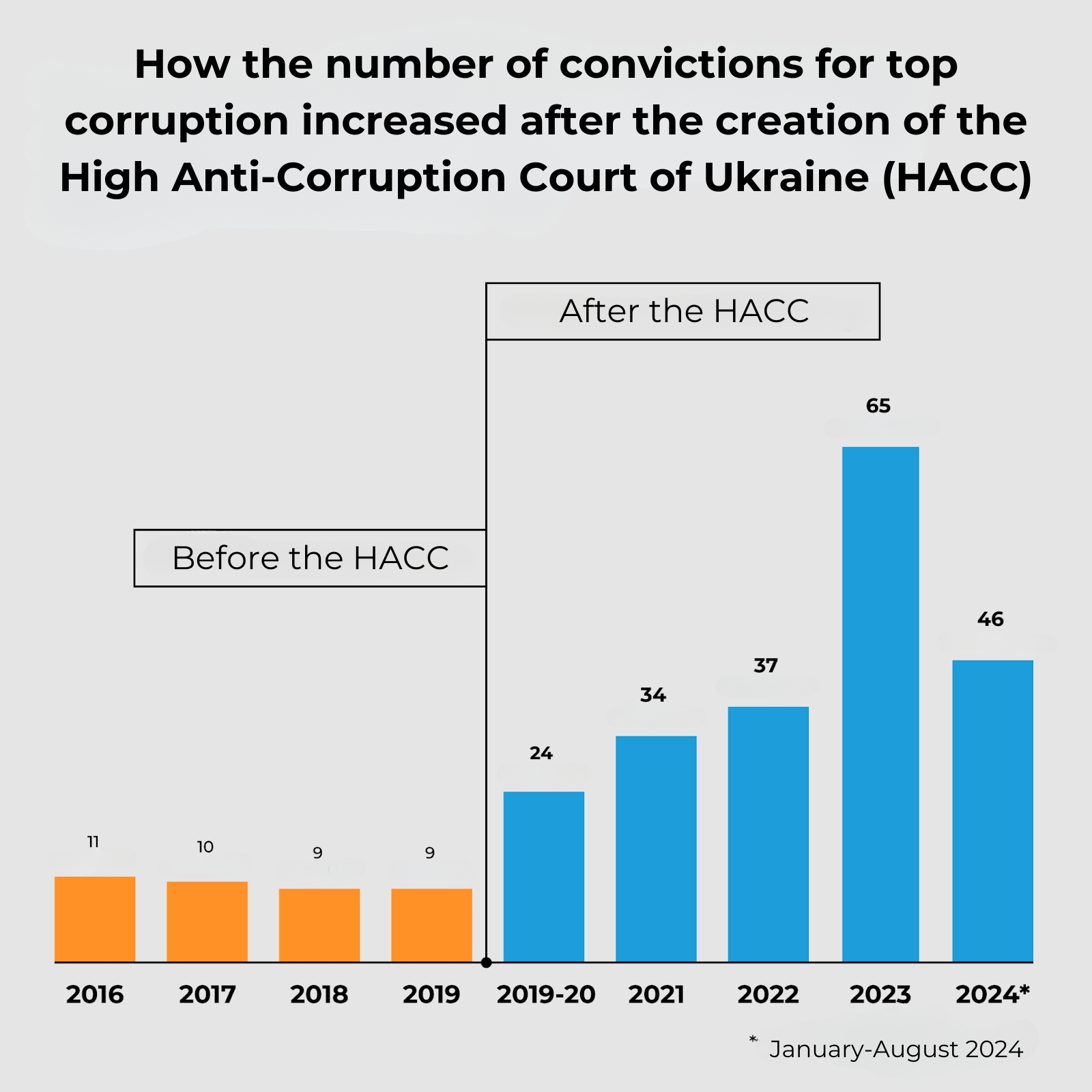

Ukraine's fight against corruption is demonstrating its deliverables: its top-corrupts are not only being investigated but also punished. This is the result of the work of the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine (HACC), which since its inception in September 2019 has worked to overcome a vicious cycle of impunity in Ukraine, where corrupt judges covered up for corrupt officials.

To date, 89% of its rulings have resulted in convictions, with the overall number of cases considered increasing yearly. This means that officials convicted of high-level corruption are finally ending up behind bars instead of finding ways to evade justice.

The court's creation was part of Ukraine’s wider anti-corruption effort after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, one of Ukraine's most sought-after changes by Ukrainians. Two new institutions were created first to investigate offenses such as bribery, abuse of power, and illicit enrichment by public officials: the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) and Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAP). Established in 2014 and 2015 respectively, these bodies were designed to operate independently from the existing prosecutor's office and present charges to the courts.

However, few of the top corrupts were actually punished: corruption cases were too sensitive or politically charged to be dealt with impartially by regular, corrupt courts. Despite numerous investigations completed, the overall number of verdicts was extremely low.

That is, until 2019, when The High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine started to operate. This court was established despite enormous resistance from the system. International experts played a key role in the selection committee to ensure the court's independence from existing bodies.

And it really works, although certain legislative changes and the selection of more judges are still needed to speed up the court's work.

The rationale for creating a separate court for such cases was that it could oversee ordinary courts and arrest corrupt judges susceptible to bribery, thus combating systemic corruption. Indeed, judges of ordinary courts became the most frequent visitors of the High Anti-Corruption Court, leaving it in handcuffs. MPs were also convicted, along with at least one former minister, while more cases against former ministers and deputy ministers have recently started.

In addition, a series of transparency reforms, including the creation of open online auctions for state procurement via the Prozorro system and the launching of public declaration of all officials’ property, significantly complicated corruption schemes.

While it is impossible to completely eradicate corruption in any country, the results of the first five years of the HACC’s work, along with NABU and SAP, have finally created a long-awaited sense of justice in Ukraine.

247 officials guilty in 186 verdicts

Roman Verbovskyi, a lawyer of Ukraine’s non-government Anti-Corruption Action Center, summarizes the HACC's achievements over five years.

The HACC passed, on average, six times more convictions for officials' corruption investigated by the National Anti-Corruption Bureau than all ordinary courts before its creation in 2016-2019 -- 33 vs. 186. Moreover, the HACC's punishment was much stricter, too: ordinary courts mostly issued verdicts based on plea agreements, with only two verdicts resulting in time behind bars.

“In one year of its operation, the HACC delivered more verdicts in the NABU cases than other courts in four years,” Verbovskyi writes.

In total, the court delivered 207 verdicts, 186 of which were guilty verdicts against 247 persons. That is, 89% of the verdicts passed by the HACC over the past five years were guilty ones. 80 of them were delivered on the basis of plea agreements.

Only 18 HACC convictions were overturned on appeal and seven on cassation review. This low reversal rate indicates that most HACC decisions are upheld by higher courts.

Some of the verdicts that have led to imprisonment include:

- Dmytro Sus, former deputy head of one of the departments of the Prosecutor General’s Office, was sentenced to 9 years with confiscation for misappropriation and sale of seized property worth UAH 814,000 ($22,000).

- Orest Furdychko, director of the Institute of Agroecology and Nature Management of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, was sentenced to 8 years in prison for taking a $300,000 bribe.

- Hennadiy Diachenko and Ivan Radyk were sentenced to 11 and 10.5 years in prison for embezzling UAH 80 million ($3.2 million) from the construction of a railroad connection between Kyiv and Boryspil airport.

- Andriy Rachkov, First Deputy Director General of the State Research and Design Institute of Titanium, received 10 years with confiscation for causing $1.258 million in damage to the company.

- Judge of the Malynovskyi District Court of Odesa, Anatolii Tselukh, was sentenced to 5 years in prison for taking a $2,500 bribe.

- Pavlo Medentsev, a judge of the Economic Court of Odesa Region, was sentenced to 9 years in prison with disqualification to hold judicial office and a special confiscation of UAH 250,000 for taking a bribe of UAH 570,000 ($23,000).

- Judge of the Brovary City District Court of Kyiv Oblast, Hanna Bilyk, was sentenced to 6 years in prison with confiscation of part of her property for extortion of EUR 1,000 for issuing a clarifying decision in favor of the company.

- Mykhailo Krenzel, the head of the Kozivsky District Court of Ternopil Oblast, was sentenced to 5 years in prison with confiscation of all property for accepting a $2,000 bribe.

- Mykhailo Pak, a judge of the Mukachevo City District Court in Zakarpattia region, was sentenced to 5 years in prison with confiscation of all property for taking a UAH 2,000 ($80) bribe.

- Judge Andriy Novak of the Holosiivskyi Court was sentenced to 7.5 years in prison with confiscation of property for accepting an $8,000 bribe.

Ukraine’s High Anti-Corruption Court flexes muscles, arrests sitting minister

Plea bargains approved by the court raised millions for Ukraine’s Armed Forces

A positive side effect of the court's work is 80 plea bargains, in which defendants admitted guilt for reduced sentences and cooperated with the court, exposing broader criminal networks.

The plea bargains approved by the HACC have traded suspended sentences in exchange for the wrongdoers' payments to the Army and damage compensation.

The case of lawyer Oleh Horetskyi

demonstrates how plea bargaining works in practice.

Horetskyi admitted to facilitating a $2.7 million bribe from tycoon Kostiantyn Zhevago to former Supreme Court Chief Justice Vsevolod Kniazev. As part of his plea deal, Horetskyi received 5 years probation and agreed to significant financial contributions: UAH 21 million ($580,000) to the Army of Drones and UAH 29 million ($800,000) of seized funds to the Armed Forces. A key condition of the deal was that Horetskyi had to provide incriminating testimony and cooperate with prosecutors. This cooperation likely contributed to the arrest of Zhevaho in absentia.

Another example features former Ecology Minister and owner of Burisma Group (gas mining holding company) Mykola Zlochevskyi. He pleaded guilty to influence peddling. His plea deal resulted in a UAH 68,000 ($1,900) fine and significant contributions: $6 million in seized bribe money to Special Operations Forces, UAH 500 million ($14 million) for military drones, and over $4.4 million in other charitable aid to the army.

Other examples involve two MPs, the Poltava mayor, and many other officials.

MP Maksym Poliakov received three years probation and a fine for illegal hotel compensation of $10,000. He contributed $30,000 to the Armed Forces, with disqualification for holding certain positions and a fine.

Former Poltava Mayor Oleksandr Mamai got a 5-year suspended sentence for misusing public funds, compensating losses and donating UAH 2 million ($56,000) to the "Army of Drones."

Former MP Oleksandr Trukhin lost his mandate after pleading guilty to accident involvement and attempted bribery of police, contributing UAH 6 million ($168,000) to the Armed Forces.

However, the effectiveness of plea bargains is limited by current legislation. A draft bill (No. 11340) aims to reform plea bargaining, but the version supported so far focuses on raising money rather than exposing criminal networks.

Confiscation of assets also brought millions for the army

The HACC played a crucial role in confiscating assets worth over UAH 15 billion ($416 million) from Russian oligarchs, collaborators, and Ukrainian traitors. Key confiscations include:

- Mykolaiv Alumina Plant and other assets of Russian billionaire Deripaska

- Aeroc, a major aerated concrete producer, owned by sanctioned oligarch Molchanov

- Vinnytsia Aviation Plant, SME Helicopters, and other companies owned by Bohuslaiev, along with UAH 630 million

- Ocean Plaza shopping center in Kyiv, owned by the sanctioned Rotenberg brothers

- PentoPack Ukraine, owned by Russian-Greek oligarch Savvidi, sold at auction for UAH 103 million.

Additionally, hundreds of other properties, including Mezhyhiria's residence of former president Victor Yanukovych, who fled the country during the Euromaidan Revolution, and shares in numerous legal entities, were confiscated.

Solving two problems can make the court's work more effective

Verbovskyi writes that, in general, two problems should be solved to make the work of HACC even more effective.

First, some grand corruption cases lack verdicts due to complex evidence and defendants abusing procedural rights, leading to years-long delays. This raises the risk of cases being dismissed due to expired statutes of limitations.

A notable case is that of Odesa Mayor Hennadiy Trukhanov, where hearings have been ongoing for nearly four years.

The solution requires certain legislative changes and the selection of more judges – a process that had been announced but hasn’t started yet.

Second, plea bargain agreements need improvement to facilitate cooperation with investigations better. Persons should be obliged not only to pay a fine and compensate for damages but also to expose the organizer or other crime.

History of the HACC's formation

The High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine (HACC) was established as a pivotal part of Ukraine's judicial reforms aimed at tackling high-level corruption, following persistent failures of ordinary courts to prosecute such cases effectively. The process of creating the HACC was lengthy, driven largely by civil society organizations and international partners who were crucial in pushing for the creation of an independent judicial body that would ensure accountability for corruption at the highest levels of government.

The High Anti-Corruption Court was officially launched on 5 September 2019. The impetus behind its formation was rooted in the widespread dissatisfaction with how cases of major corruption were repeatedly stalled or sabotaged by ordinary courts. Civil society groups recognized the need for a specialized body, as existing judicial structures were compromised by corruption and lacked the credibility to handle cases involving top officials.

To safeguard the independence and integrity of the HACC, the participation of international experts in the judge selection process was made a legal requirement, with international observers having veto power to exclude unsuitable candidates from the bench.

This was a key element that ensured that the court could operate independently and free from undue political influence, as it prevented the appointment of judges with questionable ethical backgrounds or political connections, which had been a major problem in previous attempts to reform the judiciary

The formation of HACC was supported by Ukraine’s international partners, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which pressured the Ukrainian government to ensure transparency in the creation process. The involvement of international experts and oversight bodies helped in filtering out corrupt or compromised candidates during the judge selection process. Despite some initial resistance from Ukrainian political entities who tried to minimize the role of these experts, the establishment of the HACC marked a significant step forward in judicial reform, driven by pressure both from within Ukrainian civil society and from the international community.

The court began its activities by focusing on top officials suspected of corruption. One notable aspect of the HACC's work was the application of civil asset forfeiture, which allowed for the confiscation of assets if it was proven that they were acquired through illicit means, without necessarily requiring a criminal conviction.

For example, the HACC upheld the first confiscation of illicit assets in 2021 when it ruled against MP Illia Kyva, confiscating his undeclared income. This represented a new, more efficient way to tackle corruption, as it bypassed the often cumbersome and easily obstructed criminal proceedings.

The Court – Euromaidan Press documentary on the creation of the Anti-Corruption Court

Related:

- Ukraine’s High Anti-Corruption Court flexes muscles, arrests sitting minister

- Sunset of the oligarchs: Ukraine’s war-time nationalization of strategic enterprises rectifies past sins

- Decentralization — a true success story from Ukraine

- Ukraine holds first-ever confiscation of illegal assets