Today, on 18 May, Ukraine commemorates the anniversary of the deportation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula indigenous people -- Crimean Tatars.

On 18 May 1944, the interior ministry of the Soviet Union (NKVD) on orders from Moscow started mass deportation of Crimean Tatars from the Peninsula. The operation lasted three days and is deemed the speediest deportation in global history. Euromaidan Press has answered top-ten questions about the 1944 Crimean Tatar deportation you always wanted to ask.

Who are the Crimeans Tatars and how did they end up in Crimea?

Crimean Tatars lived in Crimea for over 1,000 years; they are its indigenous population. In 2014, about 300,000 Crimean Tatars lived in the Ukrainian peninsula -- about 10% of its total population. They are part of the East European Turkic ethnic group and nation of the Islamic religion. They have their official language, flag, and culture. And their homeland has been occupied by Russia since 2014.

The Crimean Tatars as a people formed in Crimea and are the descendants of various peoples who lived in the peninsula in different times of history, such as Tauri, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Greeks, Goths, Bulgars, Khazars, Pechenegs, Italians, and Circassians. These ethnic groups had common territory, the Turkic language, and the Islamic religion. The Crimean Tatar language developed on the basis of the Cuman language with a slight Oghuz influence.

Well, 10% isn’t much. Was it always that way?

Great question! Actually, no. Like all indigenous nations, the Crimean Tatars once made up the majority of the population of their homeland and for nearly 350 years had their own state, the Crimean Khanate.

But after its first occupation of Crimea in 1783, the Russian Empire did everything to drive them out and replace them with ethnic Russians: the Turkic nation was deemed an untrustworthy subject of the Tsar. Before the Russian Empire annexed Crimea in 1783, the number of Crimean Tatars living in the Crimean Khanate, a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, was estimated at over 5 million.

Afterward, their number plummeted. Terror of the Russian military forces and anti-Tatar politics of the Russian Empire and the destruction of their social and economic life forced Crimean Tatars to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. Another migration followed the Crimean War, which ended in 1856.

The Crimean Tatar population, which was estimated to be over five million during the Crimean Khanate rule, decreased to less than 300,000 and became a minority in their ancestral homeland. The Russian share of the population increased, proportionally.

Because of the Crimean Tatars’ continued emigration from the Russian Empire, there exists a sizable Crimean Tatar diaspora in the world. Approximately 3 million Crimean Tatars live in modern-day Türkiye; one of them is the Turkish ambassador to Ukraine. In 1921, when Crimea became part of Soviet Russia, the Crimean Tatars constituted around 20 % of the peninsula’s inhabitants.

The 1930s saw the tightening of Soviet policies towards ethnic groups, including Crimean Tatars. Soviet repressions, including arrests, deportations, and executions of prosperous peasants (dekulakization); communal farming, the Holodomor famine; and political repressions against dissidents set Crimean Tatars against the state.

Wait, I thought Crimea was always Russian?

That, among many others, is a myth Russia spreads to justify its occupations. Crimea was a homeland to many peoples, but if anything, Crimea rightfully belongs to its indigenous population, the Crimean Tatars, while Russia’s primary interest in Crimea, both back in the XVIII century and today, is a military one.

Controlling Crimea means controlling the Black Sea, and that is no minor thing for Russia, strategically speaking. Before the Russian occupation, Crimea “belonged” to the Crimean Khanate, which proclaimed itself a successor of the Golden Horde, for 342 years: from 1441 to 1783.

That is roughly twice less than the time Crimea spent as part of Russia before it was occupied once again in 2014: a total of 177 years (1783-1917; 1921-1954). In 1954, Crimea was transferred from Soviet Russia to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which rebuilt Crimea from its post-WWII ruins.

But the Russian public has long been encouraged to view Crimea as native Russian land. This has led to widespread acceptance of the idea that the 2014 Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea was somehow justified as an act of “historical justice.” However, these claims do not match the reality of Crimean history.

The 2014 annexation of Crimea was actually the fourth Russian attempt to claim the peninsula in the past 250 years. On each occasion, these efforts have ultimately failed. Hereis a good video about that.

Speaking of Russia’s military interest in Crimea, since the occupation in 2014, it has greatly expanded its military presence there, turning the peninsula into its strategically located military base. In spring 2021, satellite photos showed that Russia had movedto Crimea new warplanes than had never been detected before (such as Su-30), this way enhancing its capacity for a military assault.

Satellite images also showedthe presence of Russian landing forces, armored infantry units, combat helicopters, recon drones, jamming equipment, and a military hospital.

According to Deputy Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Serhii Naiev, in 2020, 32,500 soldiers of the Russian Federation were located in Crimea.

Russia's occupation of Crimea in 2014 served as a springboard for its full-scale invasion in 2022. The occupied peninsula is crucial to Russian attempts to occupy Ukraine, reinforcing the occupation regiment of southern Ukraine and serving as a launchpad for missile attacks against Ukrainian infrastructure.

So how did the 1944 deportation happen?

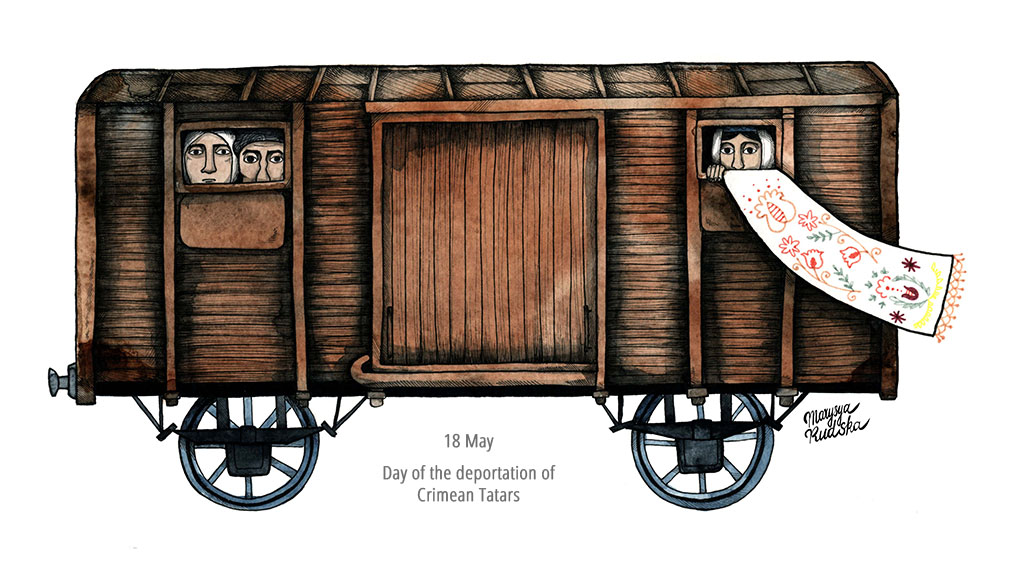

On 18-20, May 1944, as many as 32,000 NKVD security officers deported around 200,000 Crimean Tatars to the Central Asian republics of the USSR. It is one of the most rapid deportations in human history: the deportees were given only 30 minutes to pack. The journey took 20-25 days. About 8,000 Crimean Tatars died on the way to their destination because of the lack of water, space, and unsanitary conditions in the cattle wagons.

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars began at 3 AM on 18 May and ended by 20 May 1944. Nearly 32,000 members of the NKVD participated in organizing the deportation. The Crimean Tatars were given only 30 minutes to pack; strict limitations were imposed on the number of personal belongings.

The deportees took only the most necessary property and a bit of food; the Soviet state confiscated the rest. The Crimean Tatars were taken by cars to the railway stations of Bakhchysarai, Dzhankoi, and Simferopol, from where they were deported to the eastern regions of the USSR.

The cattle wagons which the Soviet authorities used for the deportation had little space, were stuffy and overcrowded. Sometimes there were no places to sit, so the deportees had to bear the road standing. What is worse, there was a lack of water and unsanitary conditions on the trains, leading to the spread of disease and death.

About 8,000 Crimean Tatars died on the way to their destination, mainly from thirst and typhus outbreak. Hakan Kirimli, a political scientist at Bilkent University in Türkiye's capital Ankara, commented on the cruelty of the deportation:

“Imagine that your child, brother, or grandfather is dying in front of your eyes. His dead body continues standing with you because there’s no room on the floor.”

According to official Soviet statistics, during the main wave of the deportation 180,014 people were moved using 67 echelons. Nearly 6,000 incriminated in collaboration were arrested and sent to Gulags. Later, an additional 3,141 Crimean Tatars were deported together with representatives of other nations.

The last echelon with the Crimean Tatars arrived in Uzbekistan on June 8. But activists of the Crimean Tatar liberation movement say the number of those deported is higher – 238,500 people, of which 205,000 were women and children. Part of the Crimean Tatars was moved to Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and to regions of Russia, including Ural and Siberia.

How did the Soviet Union justify the deportation?

The Soviet authorities made a blanket accusation against the Crimean Tatars, denouncing them as collaborators of the Nazi occupation regime during 1942–1943. Six days after the Soviet Army liberated Crimea, the “collaborators” were deported as a means of punishment.

This reason for the collective reprisal was purely nominal because collaborators were found in all occupied USSR territories regardless of their nationality, but the majority fought against the Nazi invasion. Hence, exile as a sanction for collaborationism is another Soviet and now Russian myth about the 1944 deportation.

The forced eviction was ordered by Joseph Stalin, the architect of many ethnic deportations of the Soviet Union. A week before the 1944 forcible deportation, the USSR issued a statement denouncing the Crimean Tatars of “treason,” “mass killing of Soviet citizens,” and collaboration with the German occupying forces.

This decision became a formal pretense for the NKVD to carry out the operation and for Soviet propagandists to create a myth of a total Crimean Tatar collaboration. The USSR also claimed there were 20,000 Crimean Tatar deserters in the army. In fact, the state mobilized 23,000 Crimean Tatars in WWII, and 9,000 of them were demobilized after the war had ended.

These numbers prove there could not have been as many deserters. The real reason behind the deportation was the USSR’s fear of its southern enemy -- Türkiye. In case of a potential war with Türkiye, Crimea would serve as the main conflict area and Crimean Tatars, having strong historic and cultural links with Türkiye, would possibly change sides.

For the same reason, the Soviet authorities also expelled other Muslim minorities from the USSR regions bordering Türkiye, such as Chechens, Ingush, Karachais, and Balkarians.

Did Crimean Tatars really collaborate with the Nazis?

Some Crimean Tatars did, along with other nations in the USSR. But more fought against the Nazis on the USSR’s side. There were collaborations of different nationalities all around the USSR. This testifies that the reason for the Soviet authorities to carry out the deportation of the Crimean Tatars was purely formal.

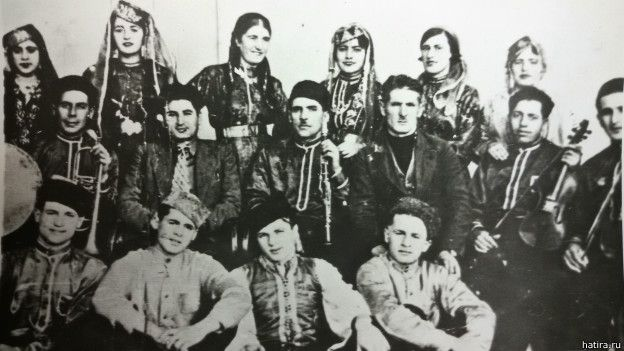

15% of adult Crimean Tatar men joined the Soviet army, including five Crimean Tatars who were awarded as Heroes of the USSR. One of them is a flying ace Amet-khan Sultan who twice received this title -- by the way, there is a great film about him banned in Russia, yet freely available online.

The USSR claimed that nearly every and all Crimean Tatar adults were collaborators. However, according to researcher Otto Pohl, between 9,000 and 20,000 joined the German army in WWII (5-11%). Some wanted to protect their cities and villages from Soviet partisans who persecuted Crimean Tatars on the basis of their nationality.

As well, some Crimean Tatars imprisoned by the Nazis tried to escape the severe conditions in the camps by joining the ranks of the German army.

Admittedly, the ratio of collaborators among the Crimean Tatars was higher than the 2% average in the occupied territories of the USSR. However, the majority of them did not join the Germans of their own free will, many were forced, Ukrainian historian Serhiy Hromenko writes.

But even so, deporting an entire nation for even a higher ratio of collaborators is too extreme a punishment. Moreover, most of those indeed collaborating with the Nazis already received their punishment from the Soviets.

5,000 of them retreated from the peninsula together with the German Army in May 1944 and eventually, those who were not killed in battle, were deported back to the Soviet Union. Additionally, the NKVD arrested 8,000 so-called "anti-Soviet elements" in Crimea itself in April-July 1944. So it is safe to assume that most Crimean Tatar collaborators ended up in Soviet prisons, where they served at least 25 years.

Most of those deported were women and children, who did not take part in hostilities; what was the purpose of punishing them? It's clear that there were other reasons for the deportation, and the myth of "mass collaboration" was only a formal pretext.

What happened to the Crimean Tatars and Crimea after the deportation?

After deportation, the USSR nationalized the property of Crimean Tatars, settled ethnic Russians and Ukrainians to the Crimean peninsula, and did everything to destroy the Crimean Tatar indigenous culture.

About 46% of the Crimean Tatars died during the first years in settlements as the result of famine and diseases. The settlements resembled concentration camps, as leaving them could get a result in 20 years in prison. Upon deportation, Soviet authorities spared no effort to eliminate traces of the Crimean Tatars in the peninsula.

In particular, 90% of toponyms of Crimean cities, villages, water bodies, and mountains were renamed from Crimean Tatar to Russian. These activities are also known as toponymic repressions. Soviets also burnt books in the Crimean Tatar language, demolished their historical monuments, and converted mosques into shops and movie theatres.

Meanwhile, the deported Crimeans suffered from dire conditions in the eastern parts of the USSR. Many of them died because of malnutrition and the absence of any medical care in the event of an outbreak of disease. For the locals, Crimean Tatars were a cheap labor force. They were settled in militarized settlements and attempts to escape cost them 20 years of imprisonment. Crimean Tatar Feride Medzhytova was deported to Uzbekistan as a little girl. She shared her memory of living in the settlement:

“Hungry and unclothed, we reached Uzbekistan, Nazarbai collective farm. We were given a tiny house [...] we could barely fit in. In 1944, my little brother Reshat was the first to die; the next year my sister Mevide died. My mom cried her heart out and lived for three days after the death of my sister.

The next day after my mom had died, a neighbor Abdulla came to share the awful news that my brother died. [...] That night, my other sister died. Two days later, one more sister died. I was left on my own. [...] Later, when my dad returned from the frontline, he searched for me. He went to the war leaving a wife and six children at home but met only me after the return. Mom died at 34, the oldest brother was 16.”

Were the Crimean Tatars ever allowed to return home?

Yes, but only in 1988. Then, the prohibition for Crimeans to return home was lifted, as a result of many years of work of a strong civil rights movement. Almost half of Crimean Tatars living in Soviet settlements returned.

Their return was marked by land conflicts with Russians and Ukrainians in the peninsula. More than ten years after the deportation, in 1956, the Crimean Tatars were allowed to leave the “Special Settlement Camps.”

However, the prohibition on their return to Crimea was not lifted. When thousands of them attempted to return to Crimea in 1967, following an official decree that exonerated the Crimean Tatars from any wrongdoing during World War II, many found that they were not welcome in their ancestral homeland.

Thousands of Crimean Tatar families, once again, were deported from Crimea by the local authorities. A powerful civil rights movement advocating for the return of the Crimean Tatars to their homeland developed. One of its icons, the Soviet dissident Mustafa Dzhemilev, spent 17 years in Soviet prisons.

Finally, only in 1988 were they officially allowed to return to Crimea. When the Crimean Tatars came home, it was to an independent Ukraine. But their homecoming was not a piece of cake, as Crimean Tatars faced housing challenges. They often had to buy out houses from which they were deported in 1944.

It would have been just from the USSR’s side to allow Crimean Tatars to return to locations they were exiled from. But the state issued laws establishing restricted residence zone which allowed Crimean Tatars to return only to specified places, such as Bakhchysarai, Lenine, Rozdolne, Saky, Simferopol, Sudak, and Chornomorske regions as well as the cities of Simferopol, Alushta, Yevpatoriia, Kerch, Sevastopol, Feodosiia, and Yalta.

The mass homecoming of Crimean Tatars caused natural and sometimes artificial property price hikes. At the same time, the prices for houses in the places of Crimean Tatars' deportation fell. This factor impeded the comeback.

The only way for Crimean Tatars was to build their own houses but the authorities declined their requests for receiving land under the pretext of its deficiency. At the same time, the USSR encouraged the reception of Crimean land by Russian-speaking populating threatening them that “Crimea will become Crimean Tatar.”

Russians in Crimea were encouraged to invite their relatives and friends to the peninsula and promised to assist them in housing and employment. From 1989 to 1991, the Soviet authorities gave 150,000 land plots to the Russian speakers.

In this situation, the Crimean Tatar National Movement, which formed in the 1950s and struggled to receive an autonomous status for Crimea and for the right of Crimean Tatars to return, encouraged Crimean Tatars to occupy free land plots to build their homes. USSR responded to this call with persecutions and by wrecking Crimean Tatars’ tent cities. D

espite this, Crimean Tatars managed to legitimize their land plots. Apart from repatriation, the Crimean Tatar National Movement’s goal was the national-territorial autonomy of Crimea in Ukraine.

On 20 January 1991, 93 % population of the peninsula voted in the referendum for the creation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea as a part of Ukraine; however, this was a territorial autonomy for the Russian-speaking population. After the occupation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine is rethinking its policies towards Crimean Tatars.

The key idea is national autonomy for Crimean Tatars which implies among other things, the functioning of the Crimean Tatar language at the level of a national language, adequate representation of Crimean Tatars in the three branches of government, adoption of laws on the status of a Crimean Tatar people in Ukraine, and restoration of the historic toponymy in Crimea.

So what was it really -- resettlement, deportation, or maybe genocide?

The term “resettlement” was used by the USSR to describe the deportation of Crimean Tatars in the denial of the illegal and cruel nature of the exile. Most doctrine and formal instruments call this event a “deportation.”

However, a considerable part of experts deems the 1944 deportation of Crimeans has the elements of genocide. Political scientist Hakan Kirimli believes the deportation of Crimean Tatars to bear all the hallmarks of genocide. He noted,

“They wanted the Crimean Tatars to completely disappear from history, and they even removed the phrase 'Crimean Tatar' from the records, saying that there would be no such people again.” He further added, “They were kept in extremely harsh conditions where they were sent, and half of them were killed.”

In 2015, the Parliament of Ukraine recognized the 1944 deportation as genocide. In 2019, Latvia and Lithuania followed suit.

Why is Russia today accused of conducting a “hybrid deportation” of Crimean Tatars?

Crimean Tatars were the major force opposing the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014. Afterward, the Russian authorities started a crackdown on Crimean Tatar activists and religious leaders, which is often termed a “hybrid deportation,” as it forces many Crimean Tatars to relocate to mainland Ukraine to escape the repressions.

As many as 10% (25,000-30,000) are estimated to have done so already. In fact, since the occupation, Russia has prohibited the Crimean Tatars from even commemorating the day of their deportation, which is banned as “extremism” and punishable by 15-20 years of imprisonment!

However, Ukraine observes the deportation of the Crimean Tatars as genocide and supports this nation as well as it can while Crimea is occupied. Since the occupation of Crimea, the Russian occupation authorities banned the Crimean Tatar Mejlis, or self-governing organ, closed down Crimean Tatar media, and ramped up political repressions against this ethnic minority. This has resulted in many Crimeans fleeing their indigenous land.

Along with the prohibition for Crimean Tatar political leaders to return to the peninsula, this amounts to a “hybrid deportation,” echoing Stalin’s deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population in 1944.

Although Ukraine made many mistakes in its initial treatment of the Crimean Tatars after they started returning from Central Asia, after the occupation, it has accelerated measures to support this indigenous nation.

In 2014, the Parliament of Ukraine issued a statement about the guarantees of the rights of Crimean Tatars as a part of the state of Ukraine and in 2015, recognized the 1944 deportation as genocide.

On an official level, Ukraine established the Day of Remembrance of Victims of the Genocide of the Crimean Tatar people a national red-letter date. On this day, Ukrainians usually observe a minute of silence, launch information campaigns and teach special school classes to spread awareness of the tragedy, organize exhibitions and gather for commemorative events.

Apart from this, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people and the Crimean Tatar TV channel ATR have now relocated to Kyiv. Settlements for the Crimean Tatars fleeing from occupied Crimea have been set up in Kherson Oblast.

Most importantly, Ukraine is mulling granting Crimean Tatars the status of a national autonomous republic within Ukraine. In 2023, 17% of Ukrainians supported this measure.

- Deportation, autonomy, and occupation in the story of one Crimean Tatar

- Ukraine calls to recognize 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars was genocide

- For Crimean Tatars, Crimea’s liberation is a question of national survival

- I survived genocide. Stories of survivors of Crimean Tatar deportation