Ukraine's Commander-in-Chief has caused a stir.

Valerii Zaluzhnyi's article in the Economist on the breakthrough Ukraine needs to beat Russia, marketed under the phrase "the Ukraine war is at a stalemate," has reportedly made Ukraine's uphill battle for US military aid even steeper amid reignited ideas of negotiations with Russia. It was rebutted by President Zelenskyy, who has taken to media to claim there is actually no stalemate in Ukraine.

Amid the obsession with the s-word, Zaluzhnyi's main point, expressed in the less-viewed PDF "Modern positional warfare and how to win it," was all but forgotten: that the war has reached a new stage, and the strategy needs to be adapted yet again.

We talked with Andriy Zagorodnyuk, Ukraine's former defense minister and chief of the Center for Defense Strategies, to understand whether Russia's invasion of Ukraine can indeed be at a stalemate, whether Ukraine can win the war, and what it needs now.

No stalemate, but slow achievement of Ukraine's goals

The main message that we heard from the article of Valerii Zaluzhnyi is that the war is at a stalemate. And we are even hearing some calls for Ukraine to start negotiating because it is considered that Ukraine cannot win the war. But what did Valerii Zaluzhnyi really say?

Let me deconstruct your question. First of all, about the stalemate. For most people, this word means there is no movement, because there is an equilibrium of the forces. Basically, the forces push each other with the same capability and might, and essentially the net assessment of capability is zero.

And that ends up with nothing happening.

Then, most people immediately compare this to 1914, World War I, those sorts of scenarios. Or the Ukrainian war, when for whole periods [between 2015-2022] there was no movement of the front line for years.

That's absolutely not the case today.

There is a massive push from the Russian side, particularly in the north from Donetsk, Avdiivka, and so on. Russians still attempt to occupy the whole Donetsk Oblast. They currently cannot say they're succeeding, but they're trying very hard and they're putting huge forces there and sustaining massive casualties.

So, it is absolutely a very, very active war. That's the first thing.

Second, we indeed don't have a net result of some forces being dramatically higher than others. Therefore, the Russians cannot achieve their goals and Ukraine is achieving its goals extremely slowly.

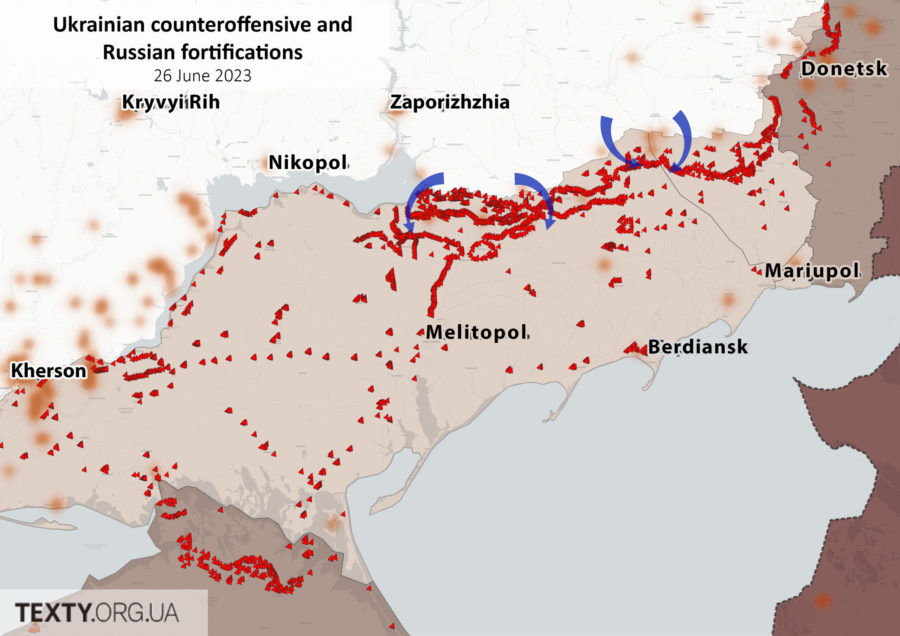

What Zaluzhnyi said is that he did not expect the counteroffensive to be so slow. It is happening: right now, we are proceeding in a number of areas in the south of Ukraine, but it's extremely difficult and very, very, slow, even compared to some conservative assessments and expectations. That's a fact.

However, his main message in the article wasn't about just stating that fact. It was that this outcome necessitates massive changes in the technological landscape of the war.

Right now, we have a whole bunch of new technologies that are incapacitating some older concepts and doctrines and some older weapons.

For example, demining. Russia used lots of mines and fortifications,a combination of so-called dragon teeth, as they call them, trenches, some walls, and, of course, minefields, and so on.

There exists breaching equipment that can go through this, but because of the drone-coordinated artillery and FPV drones, the Russians attack most of this equipment, and so it's incapable of achieving results.

So, we're talking about a very technical problem in this case.

And this technical problem leads to very, very slow movement, because people have to do the demining by hand, risking their lives to the extreme. In many cases, it's demined by hand under fire. And that, of course, slows the process down.

And that's what Zaluzhnyi was talking about. Unfortunately, in this article, the word "stalemate" was put in the lede. And then, during the promotion of the article, this was constantly reiterated.

So, like majority of observers looked at the, so to speak, stalemate recognition and not the actual message, which was to turn attention to the technological landscape of the war.

This is extremely important and we need to have a very clear technical strategy for this war together with our allies, because this is crucial for Ukraine's victory.

The option of negotiations simply does not exist

Now, the second part of your question is about some people saying: well, if Ukraine cannot win, we need to start negotiating.

This also has a problem, because negotiations are entirely futile and there is no reason to believe that Russia will go for any negotiations, especially if Ukraine is not smashing and succeeding.

There is an idea that Ukraine and the coalition supposedly always have an off-ramp: negotiations. This idea is utterly false. It's unsubstantiated and very dangerous, because some people think that this off-ramp actually exists, so why not use it.

In reality, it's completely unavailable.

Russia is not going to stop. They will be proceeding. And so, if, for example, the military assistance to Ukraine shrinks, Russia will just have more chances to proceed.

One needs to be extremely careful about mentioning these things: they are absolutely misleading.

You mentioned some very important things about how the nature of the war has changed recently. How else has the war changed in the last year, and is the West aware of this?

No, the West in general is not aware of this. I mean, many analysts are aware, but all the people I've spoken to confirm that the extent to which the technological landscape of the war has changed and how this has impacted the doctrines of a new generation of war is still not adequately assessed.

This is concerning because it's a very dangerous misunderstanding of what's happening.

Indeed, the context of the war has changed very much, particularly, because of the use of first-person view drones and other related technologies like electronic warfare and the gliding bombs which Russia started to use early this year.

Basically, a gliding bomb is an old aerial bomb with GPS and wings, which help it glide. It doesn't have an engine, but it can glide for many kilometers.

And the magnitude of the bomb is extremely high. It's 10-30 times heavier than Shahed drones, carrying 500-1,500 tons of explosives. They're doing very substantial damage.

There are ways to intercept them, particularly with aviation. If Ukraine had F-16s now, we would not let the Russian planes into the area and basically keep them away.

But the decisions with F-16s were, as you know, made quite late, and so we still are in the training process, which is obviously going to take time.

FPV drones are incredibly impactful. And when I'm talking about FPV drones, we need to understand that we're not talking just about small drones, which cost $500. These are present as well, but Russians are using first-person view guided drones, such as Lancet, for example, which are quite powerful.

Russia’s new Lancet suicide drone model evades Ukraine’s defenses

And they can go 70 kilometers deep, as we found out recently.

Ukraine has technologies to introduce, which would be able to at least address those challenges and create barriers for that new generation type of warfare, as well as introduce our own competing warfare.

But to do that, we need Ukraine and our partners to work together on a very clear technology strategy. And I don't think that exists, because I don't think our partners appreciate what type of a new war we are in.

Are you saying that the current Western technological capabilities are not actually sufficient for a kind of war and that Ukraine has the know-how?

Some conventional doctrines and conventional weapons are indeed not capable.

For example, the mining equipment I mentioned. It's good equipment and when it reaches the minefields, it works quite well. So, there's nothing wrong with the equipment, except that now, if an FPV kamikaze drone hits that equipment, it explodes before it reaches the minefield and kills everyone around in a radius of about 60-200 meters.

So, it becomes dangerous for everybody. So, the question is, are these charges, like the demining charges, they are working well? Yes, they still work well. But the doctrine of using them is quite irrelevant now and we need to change the way we deliver those charges to the minefields. And this is not clear at the moment.

War enters a new phase, for which no doctrines yet exist

There are a lot of assessments that the Ukrainian counter-offensive has failed. What is your view?

There are a lot of people who have been waiting for that to happen. Many analysts who predicted Ukraine would fail two weeks after the start of the war now say, "oh, we told you, Ukraine is not going to win. We told you back then, and now it's just happening a year and a half later."

There's a lot of that in the information space right now. And it is completely unconstructive.

First of all, every long war has situations which didn't work according to the plan.

If you look at the war in Afghanistan and Iraq, many of the operational plans completely failed and had to be adapted, after which they worked out in an adapted way.

But you can always not do that and just claim something a failure and then sit down and say, okay, fine, we're not going to do anything.

That's a very weak strategy. And I don't think it can be opposed strongly enough.

For example, in the middle of the war in Iraq, after an initial phase that was quite favorable to the Western coalition, they found out that they were in a very different war from the one for which they were getting prepared.

Russian drones, jamming stations stymie Ukrainian advance near Robotyne

They were in a so-called insurgency war, for which doctrines were not even written.

And the understanding of that war wasn't even conceived. People were just realizing what it meant. And therefore, it was hard to fight against that war.

Then, there was a lot of rethinking, assessments made, and doctrinal work done, as well as operational planning and reshaping in order to adapt to this war.

This happens in every single war after it passes the initial phase. And in that, I'm talking about the clash of the capabilities which existed prior to the war.

So essentially, the capabilities of two sides existed before the war; then they clashed, and people expected some result, and then some other result happened.

For instance, the Russians planned that their capabilities were enough to crush Ukraine very quickly. And that didn't happen, and Russia failed. And Ukraine returned more than half of its territory.

Then there was the first adaptation: Ukraine was running out of weapons and the West luckily gave a hand, which is extremely appreciated.

And there was another phase where, using Western weapons, Ukraine could claim more territory, particularly in the second half of 2022 [during the Kharkiv and Kherson counteroffensive - Ed].

But we couldn't expect that phase to run forever. And so we see more adaptation. Things change because of technological innovations.

Now we see a new phase, and that phase coincided with Ukraine's 2023 counteroffensive.

So, yes, the counteroffensive did not go according to the original expectations. But we need to understand that adaptation and changes are normal in a longer type of conflict.

Valerii Zaluzhnyi writes about the need to transition from a positional war to a maneuver war and even gives a scheme of how to achieve this. Is this your view also that we need to shift to a maneuver war?

First of all, I'm not going to object to Zaluzhnyi; he knows more than probably anyone else on Earth about this war. We don't have even a fraction of the information which he has.

The only thing is that positional and maneuver in this particular case are going to change very quickly between each other depending on the balance of the sides.

So, if the Russians are introducing something and they're feeling they can have the upper hand, that particular phase is going to be very much a maneuver one, because they would be actively trying to advance, which is happening right now in north of Donetsk.

But then, in other parts, it could be a positional war, because Russians are not applying much effort there, so more or less standing still.

We have a very long front line, 1,500 kilometers; it's not going to be the same everywhere.

So, one spot could experience maneuver warfare one day and positional warfare the next day, and in different places, it could be a different war.

But we cannot expect the outcome of this war to be like World War I, when for years, the sides were sitting in trenches and just shooting each other. The Russians are not going to do that. They have money and production resources, they're going to make more artillery shells and bring more people which they don't care if they lose. This will all increase; their intent is not just to sit and wait for a year.

Three things Ukraine needs to win the war against Russia

It sounds like the Russians are mobilizing. Can Ukraine win this war, and what does Ukraine need to do that?

Yes, Ukraine can absolutely win this war, and I think it will win this war. But we need to do certain things for that.

- First of all, we need the coalition to want Ukraine to win this war and stop being hesitant about that. Because that hesitation is just pathetic, to be honest, in many cases. The coalition invested hundreds of billions into Ukraine and they still cannot entertain the idea of its victory. It's long past due for us to get on the same page of where we're going.

- Secondly, people have to throw away the idea that negotiation off-ramp is possible. It is not.

- Thirdly, when we decide that we're going to win (and Ukraine decided that from the very beginning), we need to have a technological fulfillment of the requested capabilities.

If that happens, then Ukraine has all the forces, and our main goal right now is to make sure that that happens.

And does the West have the instruments that Ukraine needs to win the war?

Some, yes. And first of all, the West has the capacity to create those instruments. It's not like they are waiting for Ukraine in the warehouse. Some are, and some are not.

But the Western coalition has all the capacity to prevail in this war. If, technologically speaking, we compare Iran and Russia and the UK, US, and EU -- come on, it is not a fair comparison.

Of course, the West can be stronger. We simply need to want that.

And why does the West not want it, then?

Because they are hesitant about the victory. Because they are too afraid to say we are going to go for victory. But we need a strategic plan for the victory. A joint strategic plan, which currently we don't have.

- Gain air superiority over Russian forces by using tactics like drone swarms, anti-drone hunter drones, radiation simulators, and electronic warfare assets.

- Breach Russian mine barriers in depth by using technologies like LiDAR sensors, smoke screens, sacrificial unmanned vehicles, water cannons, and anti-drone guns.

- Increase the effectiveness of counter-battery efforts by building local GPS fields, using kamikaze drones, combining counter-battery with deception, and upgrading artillery reconnaissance.

- Create and prepare the necessary reserves through improving mobilization systems, training programs, and combat internships.

- Enhance electronic warfare capabilities by deploying new situational awareness systems, gaining access to partner nations' signal intelligence, using electronic warfare drones, organizing counter-EW measures, and developing advanced domestic EW systems.

- Improve command and control through single information environments, information superiority, and coordination of subordinate forces and assets.

- Optimize logistics support by building Ukraine's defense industry, creating asymmetric arsenals, and producing new indigenous weapons, while protecting logistics infrastructure.

Related:

- Ukraine’s Commander-in-Chief reveals his strategy to defeat Russia

- Russian drones, jamming stations stymie Ukrainian advance near Robotyne

- Zelenskyy announces change in strategy after the article by Ukraine’s top general Zaluzhnyi, where he described key challenges

- Is the West’s slow-walk strategy dooming Ukraine? General Zaluzhnyi’s memo says yes