Article by: Janine di Giovanni, The Reckoning Project

Locking down the truth during a conflict is critical for post-war reconciliation, American war correspondent Janine di Giovanni told the audience during her talk at the 2023 Lviv Media Forum in Ukraine.

Here is an adapted version of di Giovanni’s speech.

Denial of war crimes, of what actually happened on the battlefield, is real, and it will happen here in Ukraine—unless we lock down the truth.

This denial is already happening today with two other recent conflicts that occurred in the 1990s: one in the former Yugoslavia, the other in Rwanda. In both cases, history is being rewritten by genocide deniers who seek to bury the truth for personal gain and power. We cannot let that happen in Ukraine. We know that the truth has been buried before here, over many decades of trans-generational trauma that's been inflicted on Ukraine from the countless wars, occupations, to the Holodomor, to the current, full-scale invasion.

This war is a brutal, unjust war, an attack on civilians who have done nothing to deserve to watch their families die, their houses scorched, their children sent to another country, and their identities erased.

But war does more than destroy buildings and homes. At its very core is the attempt to erode society. It dissolves the infrastructure of family, of ordinary life. The real intent behind Putin's gruesome playbook, which, by the way, is very similar to the playbook he used in Syria, where I spent many years, and in Chechnya, where I witnessed the fall of Grozny in 2000. He wants to whittle down the very concept of your identity, of what it means to be Ukrainian. His greatest fury is that you have fought back, and you refuse to be defeated.

This war will end. It might end in six months. It might end in three years. I don't have a prediction because, as a conflict analyst, everywhere I've ever lived, studied, or taught, war ended differently.

There are two real ways to go about it. The first way is that “wars end badly,” with fighting resuming a few decades later.

The second is that “wars end well,” and when I say “well,” I'm taking into account the horrible things that happen. It means that justice is given, and there is a plan for transitional justice. When justice is given back to victims of horrific crimes, only then, and only then, can there be any kind of healing. Only then, can societies begin to get back the strength that Mr. Putin is trying to take away from you.

When countries eventually enter the period known as healing or reconstruction or transitional justice, that's when the real healing starts. Can the people and the land actually be healed after such a brutal assault? They can if everyone here works towards a future that will always incorporate your historical memory. We also have to move beyond a wartime mentality and begin to live again with the notion of peace. But we must never, ever forget the times of darkness and the times of evil.

Iraq's perpetual cycle of violence and despair

I want to give a few examples of past wars and trauma, and countries that have managed to heal, but also countries that are still stuck in a cycle of violence and are absolutely unable to move forward towards healing.

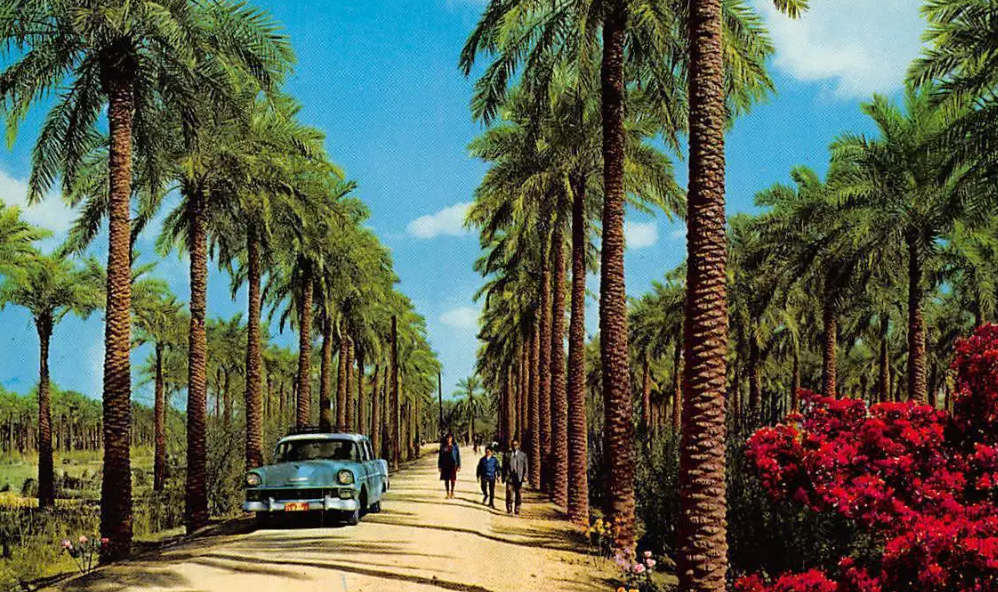

Iraq is a country that makes me unbelievably sad. It is still enveloped in devastating, heart-wrenching pain. I remember so well, before the invasion of Iraq in 2003 when Saddam Hussein was still in power, driving from the very south, Basra, to the north, Mosul, with an Iraqi friend in an Oldsmobile from the ‘70s, and seeing these incredibly beautiful date trees by the side of the road. Those trees line nearly every highway in Iraq. “Those date trees are symbolic of all of the souls of the Iraqi people through history, from Mesopotamia to modern-day Iraq,” my friend told me.

A year later, the violence in Iraq was on an epic scale that none of us could have imagined. We knew the Iraqi people would never accept an occupation, but none of us really could foresee how desperately the souls of the Iraqi people would be ripped apart. “Until the violence ends in our country, but also in our hearts, until the vengeance ends, we will never be free again. We'll never be as free as those date trees," my friend told me.

The occupation of Iraq led to horrific chaos, disorder, death, and destruction. It was a time when car bombs went off constantly. So, if you were a journalist and you were in a car stuck in traffic, it was absolutely the most terrifying thing, because it meant your chances of being near a car bomb were much higher. It was a time when ordinary people were kidnapped from their homes, right off the streets, from their jobs. It was a time of insurgency, sectarian violence, Sunni versus Shia, of intense vengeance.

And then, in 2014, the Islamic state began to grow and carve out a kingdom that none of us thought could happen in the 21st century—a medieval, cruel kingdom where women and children were sold on a stage as slaves; where journalists, many of our friends, were beheaded simply for trying to tell the story; where ancient Christian people, the Assyrians who had lived in Mesopotamia and Iraq for thousands of years, were forced to convert to Islam or pay a tax, or be extinguished forever.

It was a time when I saw prison cells where desperate prisoners carved out their last words in blood. It was a time when I saw hanging nooses in Abu Ghraib prison, where innocent people were executed just for being in the wrong party or being the wrong sect. It was a time when I felt like I stood every day next to an open mass grave that was being unearthed, with women, mothers, sisters, and family members screaming and howling as they recognized a piece of cloth on a skeleton that came up. People had disappeared for years in Saddam's Iraq, and they were finally finding out what happened to them. But the occupation unleashed pain, anger, and a cycle of vengeance—rather than healing. It was a terrible time of killing, blood, and genocide.

During those dark days, I had another friend who built a farm in the middle of the city, in the middle of Iraq. She trained Iraqi men and women to tend the soil because she believed they had been brutally damaged and traumatized by war, as deep as the soil itself. They were traumatized not just by the chemicals from the bombs, but the trans-generational issues they had endured. The fear, the anger, the sorrow were all buried in that soil, and my friend wanted the earth to be restored. In a sense, she felt this would bring healing.

Today, fast forward to 2023, the war in Iraq is over. I guess the US withdrew in 2011 but returned in 2014 to fight ISIS. ISIS was essentially defeated in 2017, but they continued to operate as insurgents. You can't kill an ideology like ISIS.

As for Iraqi society, many people are trying to work towards healing. But without addressing the historical memory and the narratives woven through the intense sorrow, it is impossible. As for the question of justice, it is moving so slowly. One way of ensuring that justice is done when war is over is by documenting the crimes whilst the war is waging.

Bosnia's elusive path to healing in the aftermath of brutality

When I think of healing, I think of another country not so far from here and not so very unlike Ukraine. This other country also sustained brutality on a level that I did not think human beings were capable of inflicting on each other, levels of cruelty, and a descent into darkness, that, in my dreams, I did not think was possible. I'm talking about Bosnia and the city of Sarajevo, as beautiful as Lviv. Many parts of Lviv remind me of Sarajevo. This city, Sarajevo, underwent a medieval siege for nearly four years without water, electricity, and where hundreds of shells fell every day.

This city was encircled by evil men who basically tried to crush the population. At one point, as a psychiatrist friend of mine estimated, the entire city had post-traumatic stress disorder. It had literally become a walking insane asylum because the people were so absolutely saturated with trauma. Outside of Sarajevo in central Eastern Bosnia, villages were being torched, women were being herded into camps, impregnated by the enemy. Men were taken to concentration camps.

One day, in a front-line village in northwest Bosnia, I was pinned down for hours by a sniper. I was hiding behind a rock and looked up and saw something that, to this day, I feel like I dreamt, because it was so surreal, though it exemplifies for me the madness of war. It was an incredibly beautiful woman who walked out from her hiding place, in the middle of the snipers, took off all her clothes, and lay down in the middle of the road, just where the snipers and the shooters were shooting. It was as if she was saying, “There is so much madness, but I will be even madder.” I wish I had dreamt this, but it's reality.

Has Bosnia healed?

Healing can only happen when there is real transitional justice—when the men and women who waged the war and brought such pain to this country are brought to justice. Bosnia did have the ICTY, the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which was set up in 1993, during the war, by the UN Security Council. I speak often with legal scholars who say this was a tremendous success. It was the first time since Nuremberg that most of the leaders, the architects of the destruction of Bosnia, were brought to The Hague.

But to me, I can't even think about Bosnian justice without tremendous sorrow, because I think of the people who actually suffered, the women who were raped—and we believe there were up to 16,000.

There were about 20 men who were indicted for those crimes. Many people saw the rapists. Many see the rapists in their villages still to this day. Many of the families whose homes were burnt in ethnic cleansing, never saw the people who torched their families’ lives go to The Hague.

So, when I look at justice, I look on the ground. Is justice going to come to the people, whose testimonies we have, from Kharkiv, from Chernihiv, from Kherson, from Mariupol? Until justice does come to those people, healing cannot begin.

Rwanda's Gacaca courts a model for justice

These are two examples of extreme places, where there has not been justice, but let's look at Rwanda.

Now, Rwanda was a place where one million people were slaughtered in one spring and summer. I have to stress that: one million people in three months. And to make it worse, most of them were killed with machetes. It's one thing to shoot someone. It's another thing to bludgeon them to death with a hack, with a machete. It's labor-intensive killing. So those people, the Hutus, who killed a million Tutsi, really wanted to kill them. They saw their faces when they were killing them. So you can imagine the pain and the aftermath of this.

I have an image that I sometimes have nightmares about still, which is that I'm standing on a road and looking for miles and miles, as far as I could see—I could see bodies piled. Really piled, like I'm almost 5 foot 8, so it's like double my height. It went on for miles, dead bodies melting in the sun. As I walked down the road to see it, I wanted to imprint it in my mind forever. There were mothers holding their children, there were babies, there were old people.

One of the influences when creating the Reckoning Project was how justice was dealt with in South Africa, through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the Gacaca courts of Rwanda. I don't know if we can use the model of Gacaca courts in Ukraine, but I hope we, in some way, can develop this.

Gacaca courts are homegrown courts that were set up in the villages, in the fields—gacaca means “field”—where the victims faced off with the perpetrators, and which were mediated by a tribal chief.

If the traditional method of justice were to remain in Rwanda, to bring justice to all of the million people who had died, it would take something like 40 years. The Gacaca courts quickened the process, hastened it, and it also did something rather remarkable: The Gacaca courts combined storytelling with legality. As people told their stories, they were beginning the first process of healing. Any trauma specialist will tell you, the only way to begin to recover from trauma is to talk about it in communities and in workshops.

Rwanda today has a lot of issues, and Paul Kagame is an incredibly tricky, benign dictator. But Rwanda has accomplished something that most international relations experts consider to be a success story in healing.

It is the same success in Sierra Leone, which had another horrific war, where the main kind of human rights violation was to cut off civilians’ hands and ask them if they wanted long sleeves or short sleeves. Civilians were used as objects to show the power of the evil Revolutionary United Front rebels.

The places I would say where there has not been healing are Syria—poor Syria, which has been completely left to die—Yemen, South Sudan, Congo, the list goes on and on. Those are just a few, but those are places where crimes have not been punished, places where the disease of impunity is going on and on.

Obligation of witnesses: recording history and seeking justice in Ukraine

Why is it essential that we record the truth as the war is going on?

An answer from the great Vietnamese writer Viet Thanh Nguyen goes like this, “All wars are fought twice: the first time on the battlefield; the second time in memory."

For me, these are such powerful words because they explain the importance of being a wartime journalist and also being a recorder of history. People always ask me, in my more than 30 years in war zones, if it's destroyed me, if it's made me bitter, if it's traumatized me, or if I feel hopeless.

And the answer is actually the opposite because, during wartime, I feel I've been privileged enough to see the greatest in people.

We see evil firsthand, but we also see remarkable goodness, courage, and resilience. I've seen ordinary people become like gods, doing extraordinary things that they never thought they would be capable of.

Superheroes really do exist, and I've seen this over and over again in Palestine, Syria, Yemen, Congo, Sierra Leone, and now in Ukraine.

I always say that I'm so privileged to do the work I do. [Journalists] are privileged to be witnesses because we hold the keys to historical memory. We are also responsible, along with the prosecutors, the lawyers, and the war crime investigators, to bring justice to post-war Ukraine.

At the Reckoning Project, we take witness statements, verify them, then they are locked down. They are there forever. No one can ever say this didn't happen because we have witness statements. No one can say it didn't happen in Bakhmut, it didn't happen in Kherson, it didn't happen in Mariupol.

Photo: Polk Azov / Telegram

It's not only our job. It is our obligation and our duty. If we have the ability to go to these places and to record them, if we can see it with our own eyes and write it down, film it, or photograph it, we must do this. We owe a debt to history. This is the only way to quicken justice.

We started The Reckoning Project out of anger. And my anger was at seeing the bad guys walk away all the time. They just would fade into villages, disappear, and take on new identities.

Radovan Karadzic pretended to be a new-age healer for years and lived in a village and treated people. Meanwhile, his victims were left behind. They couldn't fade away, nor could they erase the horrific things that happened to them.

Years after the Rwandan genocide, the architects of it are still running around freely. But the million people they killed will never be on this earth again, nor will their families ever recover from it.

Sometimes people ask, why do you and your team do what you do? It's hard work. It's sad work. Because I know we're going to get these guys. I absolutely know it.

Is justice possible in Ukraine? Absolutely. It is. It must be. It has to happen if we want to break this cycle of violence and recurring conflict. In times of great darkness, and in times of evil, we always have choices. We do nothing, we turn away, or we do the right thing. The right thing now, for Ukrainian journalists, now, is to record the truth.

As Albert Camus said: ”In such a world of conflict, victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners.”

Not only are we as journalists, human rights monitors, not on the side of the executioners, but we are determined that those people will not walk away from their crimes. We will get them.

Adapted by Orysia Hrudka, edited by Mike Cronin

Janine di Giovanni leads The Reckoning Project, which documents war crimes in Ukraine. The American war correspondent has more than three decades of experience, spanning 19 conflicts and three genocides. Di Giovanni has witnessed the devastating impact of war and is now covering her third Vladimir Putin-led conflict. Di Giovanni discussed ways to achieve true justice and reconciliation in post-war Ukraine at the Lviv Media Forum in May.