Why is Ukraine's counteroffensive so slow, and does still stand a chance? Would it be catastrophic to put it off for a year? Will Ukraine's time run up after the fall of 2022? Is the West's strategy of escalation management showing any cracks? Mykola Bielieskov, research fellow with the National Institute for Strategic Studies and senior analyst at the Come Back Alive Foundation, offers a dose of realism.

We met Mykola in our studio in Kyiv as part of the Patron Talks series, where Euromaidan Press supporters on Patreon meet incredible people who share incredible stories of Ukraine’s fight for survival. Become one of them or see other ways to support us here.

Ukraine's new counteroffensive strategy: slow attrition process ongoing

All our eyes are on Ukraine's counter-offensive, and we have heard a lot of criticism that it's going too slow. Meanwhile, Ukraine is saying that it didn't even start, while the US is saying it's not over yet. And the Wall Street Journal recently published a piece saying that Western officials are already preparing for the long haul to support Ukraine's efforts in 2024. So, what is your assessment of the situation? How is the counter-offensive going, and what can we expect?

I think we are at a quite interesting moment, because from different perspectives, people with different ideas can pick different evidence to prove their point. So, the people who believe this offensive is stalled or failed can point to the little territory that has changed hands as evidence. And unfortunately, there is some media coverage, especially in Western media, presenting things this way.

But from the Ukrainian perspective that was adopted in mid-June, we saw that using mechanized assaults would not quickly penetrate Russian defenses. So we started a slow attrition process to undermine their defense system based on artillery, electronic warfare, and air defense. We see daily evidence that this is working by destroying dozens of Russian artillery pieces. This campaign of destruction is proving effective.

So for me, the critical question is whether we can sustain this tempo of destruction to create an opening for mechanized troops. We have time constraints because this offensive can't go on indefinitely before we start to deteriorate.

So it's an open question if this new approach will produce the ultimate territorial result people demand, even if we are successfully destroying equipment.

The Russians are stoic in defense, not allowing elastic maneuvers, trying to keep every inch of land. We especially see little progress in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. But it leaves them without reserves, which gives us a chance to exhaust them before exhausting ourselves.

The new Ukrainian approach: a proper attrition rate

You mentioned a new approach. What is this new approach, actually? Because we've seen Ukrainian counter-offensives in Kharkiv Oblast and in Kherson Oblast, and right now Ukraine's efforts have been compared to pounding supply lines and control points like in Kherson. So what's new this time? What is Ukraine doing differently?

Each situation is unique, and everything depends on context, which is very different here. The current situation is more similar to Kherson, but despite similarities, there are differences.

And there are two major problems.

- The Russians had more time to get prepared. During the liberation of Kherson in 2022, they also laid mines, but it was more chaotic. And the Russian officers of the operational level of war are not stupid; they calculated where approximately the next Ukrainian offensive might be and got more prepared. Last year, my and colleagues and I discussed what could come next, including possible avenues for the Ukrainian offensive. We agreed that the most promising venue is Melitopol and Berdiansk. If it was evident for us, it was also evident for the Russians, therefore they got prepared.

Also, the Russians are finally fighting by the textbook. They prepared a classic defense. There are two fortified lines, preceded by the forward line that doesn't have major fortifications but is still heavily mined with strong points.

- We cannot fully isolate the Russians. Unlike the Kherson counteroffensive in 2022, when a major grouping of forces was dependent on just a couple of major, vulnerable river crossings that were vulnerable to constant Ukrainian barrages of MLRS, the current situation is different. We're trying to destroy all the links between South Mainland and temporarily occupied Crimea, but we are not that successful compared with the situation with Kherson.

We are doing our best with continuous strikes. We started at the end of July and, specifically, there are sustained strikes targeting Chohnar, both the railway and automobile connections. But they are not sufficient to recreate the semi-isolated condition of the Russian grouping of forces like it was in November 2022 in Kherson Oblast on the west bank of Dnipro, when they had no other way out but just to withdraw.

At the beginning of June 2023, Ukraine tried probing attacks at the company level with a couple of mechanized companies. We've seen that without suppressing Russian artillery, throwing in mechanized formations is suicidal because of the deadly combination of Russian mines and tube and rocket artillery. It's not only about mines, as some media say, it's this combination.

That's why we decided to start from different sides. First, to destroy tube and rocket artillery and then move safely to the mines, instead of trying to breach the mines without fully suppressing Russian artillery. That's the essence of the new Ukrainian approach: Ukraine placed its bets on a proper attrition rate, creating a safe environment for demining and then moving on.

But this is only one part of this approach. There are also in-depth strikes targeting links between the South Mainland and Crimea. And another one is simultaneously pinning as many Russian forces as possible to prevent Russians from maneuvering reserves, which is why they currently have this problem with the deficit of reserves.

Even as we see recently, they redeployed some paratroopers from Kherson Oblast to the Zaporizhzhia Oblast. And that's why we try to prevent their maneuver and again to exhaust the Russians sooner than they exhaust us.

Ukraine’s counteroffensive near Kharkiv: what enabled the Balakliia blitzkrieg

Do you think it's possible to exhaust the Russians sooner when they have so many more troops and artillery in reserves?

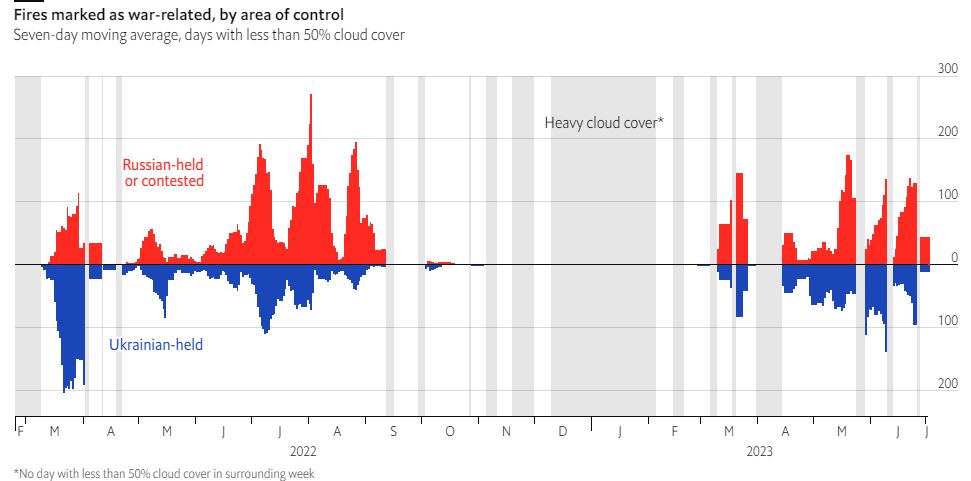

For this specific operation, I'd say the chances are decent. Of course, I can't say for certain. But we've increased our rate of fire - before this offensive, firing 3,000 shells a day was an achievement. Now we're using 8,000. The Economist has good analysis measuring fires related to war, and our strikes are comparable to Russia's.

For sure, the longer this war goes on, the more challenging it is for Ukraine to sustain it; time will play in Russian favor. But if talking about this specific situation, I would say that Ukraine and its partners did their best, especially increasing the amount of shells we have, and thanks to the recent US decision to provide cluster munitions.

You mentioned that Ukraine has not been able to cut off the Russian grouping in Crimea. Is that even possible? Is it possible to isolate Crimea?

Maybe not completely. But even forcing reliance on eastern crossings instead of the short Chonhar route would buy critical time. It would mean in a decisive fight, Russia feels a shortage of ammo and fuel. The Chonhar route is key for logistics. If we can destroy those crossings, it makes everything take longer. They can't sustain forces with only the mainland route, so we'd gain a major advantage.

This means more opportunities for our frontline formations to finally create a preponderance of forces and finally wear down Russian forces at certain points and create an opening for a maneuver formation. Sure, when there is a land link through Armiansk, Crimea is difficult to isolate fully, but it's about gaining critical time by prolonging the period when the Russians receive all necessary logistical support.

We also do our best to destroy the Crimea bridge. We recently got another bunch of evidence, rough footage from the employment of Ukrainian unmanned surface vehicles, and they are quite good, I would say. It's a challenge, but we're doing our best to isolate the Russian grouping of forces, not only at Chonhar but also on this artificial unlawful Crimean bridge that is a fully legitimate military target.

Imagine that Ukraine fully destroys the Kerch bridge: what would happen then?

It would change the situation 180° in Ukraine's favor because if even the Russians manage to preserve the land connection, it won't be enough to sustain their grouping of forces: the capacity of their railway lines via the mainland is insufficient; in some places, there is only one line of tracks, instead of two. It means that the Russians would not be able to sustain and employ this grouping of forces.

And to a certain extent, it would be a repetition of the situation in 1920, when the Russian White movement was simply constrained to this peninsula, without sufficient resources to sustain large-scale fighting. So that's why the bridge is our number one target and we are doing our best to destroy this unlawful creature of the Russian regime.

Ukraine's window of opportunity not closing this fall

You mentioned that Ukraine has a window of opportunity still before winter comes. The Czech President Petr Pavel, a NATO officer, has repeatedly stated that, actually, that's all the time Ukraine has. He has hinted that the land Ukraine manages to regain in this counteroffensive, that basically will be the result of the war, and then Western support will run out. Do you see any signs of that happening?

I can understand based on what data he is making this conclusion. It is true that our Western partners still need time to raise industrial capacity and increase the production of items like high-explosive artillery shells to meet our needs. We need at least 90,000 155mm high explosive shells per month, while the US now only produces 24,000 shells, meaning there is still a gap. I think this may be the main reason President Pavel is making this kind of conclusion.

We were already in a similar situation back in spring 2022, at the end of May and early April, when Ukraine either needed to decrease the level of its political ambitions, or partners needed to provide more assistance.

Even if we are unable to sustain offensive operations, it does not mean we need to conclude some kind of political agreement. I'm not the president of Ukraine, but if it were up to me, I would first switch to strategic defense for some time until the West raises production capacity, as decisions for this have already been made. In the meantime, I would improvise by relying on makeshift solutions like kamikaze FPV drones, UAV technology, and so on.

Publicly, I would say this: we are not going to buy a fake sense of normalcy at the expense of the Ukrainian people and territories, as we did earlier [in the Minsk agreements - Ed].. Do not try to prod me tacitly into kinds of agreements because for me, it is very difficult to envision any agreement with Russia.

Yes, there is a gap in industrial and production capacity. But this gap does not mean we should make any agreement in the meantime that would certainly favor Russia, allowing it to regroup. Of course, the major challenge is sustaining the coalition of dozens of countries, which is quite difficult, especially in democratic nations.

But the most important factor is the will of Ukrainians to fight. If Ukrainians are willing to continue fighting - whether in defensive or offensive mode is secondary - let's be honest, the West has very little room to maneuver. Because if they say publicly that they will not support us, it would undermine the West's moral authority and strategy.

Do you hear any increase in these voices that are pushing Ukraine towards some sort of negotiations and agreements with Russia?

We could interpret President Pavel's statement as reflecting a sense of inevitability to a certain extent, but I will not do that. I would simply say he is stating some obvious facts: there are gaps in capabilities from time to time. There are always some people in Western media and academia subscribing to the view that this war is unwinnable, and sooner or later Ukraine will have to compromise. I can say this group seems to be growing larger.

Of course, they would gain more arguments to use if Ukraine is not successful in offensives. That is why the stakes are high in this offensive. But again, it is Ukraine's sovereign decision whether to keep pressing the offensive or halt operations to preserve forces and ammunition.

Let's be honest: experts have admitted the slowness of the West in providing new packages of equipment decreased Ukraine's chances for success here. So it is not only about Ukraine's deficiencies in combined arms capabilities - that point is universally emphasized. It is also about the speed of decisions made and their implementation.

Again, I do not like to play the blame game, but let's be frank: the net result is a result of many decisions, not only those made in Ukraine. In that sense, Ukraine alone cannot be blamed. So for me, the situation remains relatively stable. Luckily, along with people ready to compromise with Russia at the expense of Ukrainian citizens and territory, there are others who recognize the problem lies in the Biden administration's half-hearted approach guided primarily by escalation management considerations, not Ukraine's interests.

My advice is: let's get prepared for a long war. There have been editorials in major Western media, in Europe and North America, about the need to prepare for a long conflict, increase industrial capacity, etc. So I am not excessively pessimistic about Ukraine's long-term chances. But again, preserving Ukrainians' will to fight is paramount.

Russian threat of unconventional escalation: its most potent weapon

One of the factors behind the West's refusal to allow its weapons to strike Russian territory is presumably this escalation management. At the same time, Ukraine says this greatly limits what it can do - basically, it's fighting with one hand tied behind its back. Do you see that stance changing anytime soon?

I would say the issue of unconventional escalation strikes employed by Russia is the most effective instrument in the Russian arsenal - even more than the Russian armed forces themselves, which have not proven very adept at combined arms warfare. Indeed, escalation threats are Russia's most potent instrument.

The situation is very mixed in this area. Most unfortunately, from the very beginning, Biden and his team publicly demonstrated a stance that avoiding direct conflict between the US/NATO and Russia was the number one priority, not upholding universal rules.

In my view, telegraphing openly from the start that preventing clashes between the superpowers mattered more than preserving Ukrainian statehood or ensuring Russia's defeat was a major mistake.

On the other hand, let's be fair: on 24 February 2022, the Biden administration did not have a blueprint for responding to outright aggression by a nuclear superpower. The Cold War experience of escalation, threats, and so on does not provide a model for this situation.

Most past conflicts were proxy wars with the superpowers behind the scenes. There was no precedent for one superpower launching all-out aggression while the other providing active resistance, as when Ukraine withstood Russia's initial assault. Resistance to the USSR's aggression in Afghanistan, in Czechoslovakia, in Hungary was quickly suppressed. Ukraine's situation, with it managing to withstand a major assault and to fight quite successfully, is rather unprecedented.

So the Biden team had to devise an approach on the fly, without existing solutions. To an extent, they have moved past purely nuclear fears and assumptions. Because, unlike the UK, the US came of age as a superpower in the nuclear era, and is more fearful and cautious about these matters. This war has provided a valuable learning experience for how to respond to aggression, which will matter for China and Taiwan too. So progress has been made.

And Russia's bet at the start was that threats of escalation and reliance on escalation management doctrine would prevent meaningful Western aid. That gamble clearly failed; Russia is furious over it.

In June especially, Russian propaganda pieces complained the West had somehow found a way to aid Ukraine and ensure Russia's "strategic failure" while avoiding escalation responsibility.

So there are positives, but also negatives: some weapon systems we still lack, others came too little or too late to fully capitalize on windows of opportunity, like September 2022 when Russia was extremely vulnerable militarily, and could have suffered its biggest military defeat.

The situation regarding escalation management is therefore mixed: Russian threats did not play out as Moscow hoped, but still carry major influence. The US has progressed in its approach but not enough to ensure Russia's decisive defeat, which explains the prospect of a prolonged war.

Regarding the weapons Ukraine doesn't have: earlier, you explained how artillery was crucial for Ukraine in the first days of the war, then how crucial it was for Ukraine to receive long strike capabilities. What weapons does Ukraine currently need the most? And how would they change the situation?

With the exception of some advanced capabilities still off the table, like ATACMS missiles - I estimate less than a 50% chance those get approved anytime soon - or fighter jets where Ukrainian pilots are still training pending a final decision, I would say the major problem now is not getting approval for new systems from the US.

We have mostly overcome those barriers and secured the needed decisions in 2022. The issue now is ensuring sustained flows and stocks of munitions. And that is a challenge, especially artillery shells.

It's not only 155mm high explosive shells. We also need more guided MLRS rockets for HIMARS, at least double current production, to meet needs. The same goes for Stinger missiles - in a year and a half of war we have used as many as the US produced in 10 years.

There are ongoing issues with air defenses too, not just fighter jets to help plug gaps between SAM systems. We need more surface-to-air missiles themselves and munitions for them. There was recent news of Lockheed Martin boosting the production of munitions for Patriot SAMs for example.

So the major task now, with a few weapon exceptions, is ensuring steady supplies, not getting initial approvals. There is a gap we need to improvise our way through over the next 12-18 months until production scales up fully to meet Ukraine's military requirements.

Then we can look at transitioning back to defense and wearing down the Russians, since their offensives have demonstrated zero combat effectiveness and heavy losses lately. Successful defensive campaigns, combined with stockpiling resources, could create openings for future counteroffensives after proper training.

The weapons situation now is thus quite different from 2022, when securing those initial approvals was the challenge. Now it's about sustaining sufficient volumes of supplies, which remains a serious test for Western military industries that previously pursued "peace dividends" and drawdowns.

The escalation management doctrine and the demotion of "strategic defeat"

But could you tell us how the psychology of this escalation management actually works? The weapons Ukraine needed were given with a great delay because of escalation fears, but were still given eventually, and the doctrine of escalation management is still there. Did the fears dissipate? What actually happened for the decision to be made? How does this work?

They make a decision to provide a certain weapon system or capability, then watch Russia's response closely.

Initially, there were assumptions that major air defense provision could trigger escalation, but that didn't happen. Same for HIMARS systems and missiles. It took a month and a half of internal debate before approving High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems with proper ammo. Those got delivered and again, no escalation materialized.

There have been greater hurdles around ATACMS missiles. With ATACMS, the Russians have been quite successful at signaling escalation could result from their provision to Ukraine. Unfortunately, our Western partners did not want to call this bluff. In talking to US experts, we agree it is a bluff - no one would actually escalate in that way because it would backfire. Even China and India have said breaching the nuclear taboo would be a point of no return.

But in the end, nobody is willing to call the bluff, even if the chance is only 1%. Again, as I said, this is a problem. And not just because of escalation management. The broader political framework is also an issue.

In 2022, evidence in Western media showed the basic US approach was to prevent Ukraine from losing and prevent an outright Russian victory - not to ensure Ukraine's ultimate triumph. The goal was sustaining Russia's so-called "strategic defeat" by inflicting major losses, nothing more.

And by the way, a very important shift occurred which few noticed. American partners no longer use the term "strategic defeat" - they now say "strategic failure." Even "strategic defeat" was too ambiguous, since Russian propaganda claimed you cannot ensure the strategic defeat of a nuclear power without retaliation. So Western rhetoric has evolved from "strategic defeat" to "strategic failure."

This is notable, because in summer 2022, Western media discussed "strategic failure" as the framework adopted internally by the Biden administration. But then in Helsinki in early summer, Blinken himself used the phrase "strategic failure."

The terminology shift is meaningful and signals a problem. In 2022, the thinking was it would be enough to foil Russia's plans. Only at the start of this year was there a change in mood, signaled at a low level - the Pentagon Spokesperson stated Ukraine needed offensive capabilities to retake territory, not just hold ground. This was not messaged by Biden or top cabinet members.

Let's be honest: our successful but limited offensives last year did not result from comprehensive aid designed to ensure success. Ukraine succeeded almost miraculously against the odds, thanks to major Russian mistakes and weaknesses, plus our excellent deception campaign before striking Kharkiv Oblast.

The reality is that Ukraine's two offensives in 2022 happened despite not having the necessary aid, amid the idea of ensuring Russia's strategic defeat and preventing Ukraine from losing. Only at the start of 2023 was a new framework introduced, at lower levels, about preparing Ukraine to retake territory for greater viability.

This painfully slow evolution of their approach has cost precious time. Meanwhile, Russia has finally opened its textbooks, analyzed likely Ukrainian axes of advance, and prepared defenses.

As you've noted today, the escalation management principle is based on giving something and seeing the reaction, and so far, there has been no escalation. So are any ideas developing that perhaps Russia will not escalate at all, and this is a faulty premise? Do you see any signs of that happening?

Unfortunately, we are approaching some limits, despite the emancipation from escalation management considerations we have seen. The limits are most visible not in specific weapons shipments, but regarding Ukraine's NATO membership.

My reading of the situation is this: everyone understands Russia is in no position to wage war, especially a conventional one, against NATO. Russia would lose if it dared to do so. But Biden does not even want technically to have the US on one side and Russia on the other in a direct war. It is not about actually fighting - just being technically in a war. That is why the administration remains risk-averse, guided by the hypothetical costs of action rather than the real costs of inaction.

I do not see any way for them to change this framework and approach, despite all the coordinated efforts by both the Ukrainian government and non-governmental groups. We are reaching the limits of overcoming escalation management thinking.

Perhaps, if we can somehow get through to Biden the idea I mentioned - that this is not only about US credibility, but his political credibility if Ukraine does not succeed - he might take asymmetric actions and provide capabilities that increase our chances for success, compensating for disadvantages in sheer firepower.

Chance to rout Russia missed in 2022

When you say that perhaps Ukraine needs to switch to defense until more ammunition is produced, what would that time give the Russians? Would they be able to set up even better fortifications and better defend the territory?

Well, for sure, time would also be used by Russians, they won't sit idle. But again, the Russian so-called constitution (in essence, it is not a constitution) says that Ukrainian Oblasts are now part of Russia, despite Russia's lack of full control over them. So at least, they need to gain control of this territory through a number of offensives. But we've seen that currently, effective offensives are beyond the Russian capacity and combat proficiency. And every failed Russian offensive creates an opening for a Ukrainian offensive.

So, the Russians would exploit this time, but it doesn't mean that Ukraine can't create grounds for offensive operations via skillfully combining both defense and offense and accumulating resources. But of course, much more effort needs to be dedicated and some time will pass before we would be in a position to launch another meaningful offensive.

Our miraculous successes in 2022 set unrealistic expectations. But the period of maximum Russian weakness was not fully exploited. Let me give you some evidence for this.

Back in summer 2022, when Ukraine considered possible local offensives, our original idea was not a frontal assault on Kherson but instead striking Melitopol first. If we had targeted Melitopol then, before fortifications were built, with the forces we have now, we could have achieved superb results, as Melitopol is the key to south Ukraine's mainland.

Many opportunities were missed. Imagine if the two army corps we have today had been available and employed back then in the Melitopol-Berdiansk direction, as we requested. When we asked our US partners to wargame such a scenario, they said we lacked the capability. That was the problem.

It was obvious Melitopol was the key, and taking it out would have negated the need for a slow, grinding push towards Kherson. That is the major issue. Future historians will have ample counterfactuals to study about what might have been possible with quicker, bolder decisions to ensure Ukraine could retake significant territory - not just in January 2023, but in the first half of 2022.

We are in an interesting situation now, because when I speak about this reckoning, some say by criticizing Biden, I only help Republicans who may capitalize on it.

Let's be honest: the two frontrunners for the Republican nomination are not pro-Ukraine. Unfortunately, the Republican Party is relinquishing its national security credentials - a huge tragedy, in my view.

But again, only Biden has himself to blame for this half-measures approach prioritizing escalation management over a clear victory. Imagine a decisive Ukrainian offensive last fall aimed at Melitopol - Russia would have been finished. But it did not happen, and only Biden bears responsibility. These are very unfortunate developments that may be exploited by his opponents, who I fully expect will keep emphasizing the idea this will be a long, indecisive war.

And some Ukrainians naively hope Trump or DeSantis might suddenly switch to more pro-Ukraine stances matching Reagan's Republican Party. But we should understand when Trump says something, he means it. The chances of a major rhetorical shift are very slim.

Again, fault lies with Biden for this flawed approach placing escalation avoidance over all else. He lost the chance for a decisive defeat of Russia - a clear victory. Because with a fall 2022 offensive against Melitopol, Russia would have been defeated decisively. But it did not happen, and Biden has only himself to blame.

Preserving Ukraine's will to fight is paramount

Regarding the Ukrainian will to fight, you have mentioned several times today that everything depends on how much Ukrainians are willing to continue fighting. How do you see that resolve developing?

Currently, if we look at sociological surveys, Ukrainians in absolute numbers say they are ready to fight and not compromise. But there is an issue here. Throughout this war, Ukraine's political leadership has had to perform a delicate balancing act.

On one hand, they try to sustain the will to fight and use it as leverage in dialogue with partners, saying "look, the will to fight is strong - please provide weapons." When this combination produces battlefield successes, it bolsters Ukrainians' will to continue fighting, which provides further evidence to partners about the need for aid.

But sustaining this long-term is a challenge without tangible results on the frontlines. In a scenario with no meaningful territorial progress, the only way to maintain the will to fight is to finally tackle issues internally - I mean settling things within Ukraine itself.

There is a discrepancy when Ukrainian governmental and non-governmental entities are raising hundreds of millions of hryvnias for drones, yet investigative journalists find budgets of similar or greater amounts allocated questionably, like repairing roads to tourist areas. These cracks can easily be exploited by Russian propaganda and information operations.

On one hand, Ukraine's leadership understands the need to remedy internal problems, increase cohesion and morale, and sustain the will to fight and endure sacrifices. On the other hand, much evidence points the other way. It is a difficult balancing act.

If we switch to a defensive posture for another year while preserving the will to fight, it means finally solving our internal issues - not having these paradoxes where people raise funds as quickly as possible while vastly larger budgets are spent dubiously.

Addressing these discrepancies will be even more critical as Russia seeks to exploit any cracks between Ukraine and its allies or domestically. As one of my professors taught, Russia sees non-military instruments like psychological operations and secret services as the most important tools, over hard power like the military. Closing these rifts will be crucial.

Sustaining the will to fight and willingness to sacrifice may require measures like decreasing consumption and dedicating more resources to the war effort here and now. That would be the task for Ukraine if we want to sustain a long-term fight because I do not believe any agreement with this regime is possible, especially given that Russian identity is increasingly based on Ukraine as an existential threat.

Even without Putin, Russia would still view us as a threat and seek to destroy us, particularly when motivated by revanchist sentiments. I see no other option than steadfast resistance. We must make our allies increase production capacity instead of reducing our ambitions.

Come Back Alive's wartime efforts: fundraising and analysis

Regarding raising funds for kamikaze drones, you're also a senior analyst at Come Back Alive Foundation. Could you please tell us about this foundation - what are your current projects, and maybe how they've changed throughout the war? Do you see any signs of people tiring out? What are the current needs? What does Ukraine need to fundraise for right now?

Come Back Alive has a very complex and interesting history. Most importantly, we have raised over 7 billion hryvnias (over $200 million) since 24 February 2022. We are the largest Ukrainian non-governmental charity supporting the armed forces by raising funds and procuring equipment critical for combined arms warfare, like various UAVs, communications gear, optics, and indirect fire systems.

We also supply a lot of hardware to the Territorial Defense Forces, which we contributed significantly to establishing in their current form. There are many ongoing projects meeting different needs simultaneously.

One is the campaign to jointly raise $235 million with United24, Ukraine's largest governmental charity, to acquire 10,000 kamikaze drones using off-the-shelf FPV technology. This exemplifies how warfare has evolved - both sides are using these improvised capabilities to offset disadvantages in firepower. It is a very lethal and relatively inexpensive way to destroy tanks, IFVs, APCs, artillery, etc. for around $1,000 per drone.

Study shows drones the cheapest, most effective in battle against Russian invasion

Another project with Nova Poshta [a major Ukrainian delivery operation - Ed] increases air defense coordination capabilities. We have multiple initiatives with Okko, a major Ukrainian fuel company, like Oko za Oko [Eye for Eye] 1.0 where raised funds procured indigenous Shark UAVs - operational drones with 70-80 km range, day/night cameras, and electronic warfare resistance. These are exactly the kinds of systems we need; the only constraint is production capacity at UkrSpecSystems.

Now we are also fundraising for Eye for Eye 2.0 to reinforce the Territorial Defense Forces, not just establish them but ensure they have basic weaponry. We raised $9 mn for 120mm mortars for each brigade, and now are providing automatic grenade launchers and smaller 82mm mortars too.

We have an interesting project on sighting systems as well. A colleague devised optics to allow indirect fire with US-provided Mk 19 automatic grenade launchers. Currently we can only use them for direct fire, but with these sights, we can lob grenades at longer ranges - greatly increasing capabilities for minimal investment. We are raising money to procure and field these sights en masse.

We are also cooperating with Kyivstar [mobile phone operator] on demining liberated areas - Ukraine now has the world's largest mined territory, which must be cleared to restore normal civilian life.

Those are some of the projects from our military procurement side. I represent the analytical branch, which has a different role. To influence policy, you need analysis and research to produce insights and recommendations. So we are expanding our analytical staff.

A recent project analyzed the Territorial Defense Forces' performance in large-scale war with Russia - their strengths, weaknesses, and potential improvements. We demonstrated their value and made the case for preserving them as a separate military branch, not reverting jurisdiction back to the Land Forces they were seconded from.

Our next study will draw lessons from the fighting to determine required capabilities across all domains of warfare for deterrence. There is a conceptual gap where everyone focuses on the day-to-day, but long-term strategic thinking about reforms is neglected. For example, pre-war debates started on the future structure of Ukraine's military, but were put aside when the invasion began.

We want to analyze the war's lessons, because despite the horrific costs, it has also validated or invalidated many assumptions - like the utility of sea denial versus sea control for Ukraine's navy. Basing force development on evidence from the war will honor those who fought and died. Relying on untested assumptions got us in trouble before, when some claimed a small professional force would suffice.

So while addressing urgent battlefield needs, we are also thinking conceptually. Good policy requires in-depth analysis, which we aim to provide while few others have the time and resources.

Ukrainian-produced Shark recon UAVs were procured for frontline units with the help of Come Back Alive. Photo: Oleh Solohub, Come Back Alive Foundation

The study on Russia sounds fascinating. Maybe you could share some conclusions with us. What is Russia actually aiming for in this war? Can we say what its goals are?

To be honest, the intense pace of events means I have not fully read my colleagues' paper yet. But I can provide my own impression of Russia's motives.

The core issue is that unlike other imperial powers, Russia never underwent a post-imperial transition. Its identity remains anchored to 19th-century notions of great power status hinging on land acquisition, not socio-economic development.

This is the biggest problem. Even if Ukraine regains all its territory, nobody will forcibly transform Russia internally the way denazification reshaped Germany after 1945. Without that fundamental change, nothing prevents a future revival of aggression in 10 or 30 years, if Russia is welcomed back by naive Western politicians.

So unfortunately, this war is just one chapter in Russian-Ukrainian confrontation, not its conclusion, if Russia does not transition to a post-imperial identity. That is why I argued before the NATO Madrid summit that the best way to spur this transition is admitting Ukraine to NATO, depriving Russia of the space to project imperial fantasies externally.

With no external outlet, Russians would be forced to focus inward on domestic reform. Bringing Ukraine into NATO would demonstrate to Russians that the supposed Western expansion was stopped and even reversed by Moscow's aggression, which backfired. It would achieve more sustainably what arms supplies aim for in the short-term, and likely at lower long-term cost.

But the problem is policymakers ignore the price of alternative actions - in this case, inaction. I predict that in 5-10 years, Western elites will agree it would have been wiser to admit Ukraine to NATO in 2022 instead of just providing weapons. It would have been cheaper in the long run.

That is our difficult task - changing the mindset of the Biden administration or any future US administration fixated on minimizing immediate risks, while forcing Ukraine to bear the brunt of this approach. It is unsustainable, despite our miracles so far. But we cannot do it alone indefinitely.

The core challenge is ensuring Russia's post-imperial transition. Without that, this tragic chapter will repeat in the Russia-Ukraine confrontation, which Moscow initiated.

Related:

- Javelins are good, but it is artillery strikes that coined Ukraine’s military success

- Study shows drones the cheapest, most effective in battle against Russian invasion

- “Stopping the modern Hitler”: snipers hold the line in Ukraine’s battle for survival

- Like Napoleon’s 1812: why Russian troops retreated from northern Ukraine

- What weapons for Ukraine would help it win the war against Russia

- Ukraine’s strategy in Russian invasion: similar to Finland’s Winter War