A Russo-centric approach towards Eastern European and Slavonic studies and related fields has long reigned supreme in Western academia. The effects were not limited to academic circles but have influenced journalists, diplomats, and policy-makers.

“Actual policies dwell upon and reflect the world view of their authors, and this worldview has been formed through education, media consumption, and everyday stereotypes. And all of the above is largely Russocentric regarding Eastern Europe,” says Valeria Korablyova, a Ukrainian professor of Eastern European Studies at Charles University in Prague.

This worldview became apparent during the current Russian invasion of Ukraine. Some Western leaders argue that Russia’s concerns and demands must be considered when discussing the region's post-war order.

They warn of the consequences of “humiliating” or breaking apart the Russian state. Even though Moscow is currently the leading source of instability in the region, many still see it as a bulwark against anarchy that could result from separatist movements and competing successor states.

“Eastern Europe is seen through Russian eyes when all the positive achievements of the empire are ascribed to Russia, while everything non-Russian is depicted as backward, dangerous, and not self-reliant,” Korablyova explains.

“Such a culturally racist reading of East European nations props (up) the alleged need for an external agency to civilize and control those ‘small nations.’ The underlying fear is that if Russia is defeated or substantially weakened, this entire space will descend into uncontrollable, dangerous chaos.”

However, recent events like the Euromaidan Revolution and Russia’s full-scale invasion have initiated a paradigm shift in Eastern European studies.

Parts of Western academia have begun “decolonizing” the subject by decoupling it from a Russia-dominated perspective.

Russo-centrism in academia and its echoes in US foreign policy

For Western scholars, Eastern Europe has long represented something of a terra incognita. The traditional distinction between the Occident and the Orient cast the East as mysterious, unknowable, and uncivilized.

The 19th century saw the establishment of the first courses and departments in Western academia dedicated to the Eastern European region. These attracted only limited interest from students.

The First World War and the Russian Revolution brought a short-lasting spike of interest, while the real game-changers proved to be the Second World War and the Cold War, as the Soviet Union came to the center of attention of the Western public.

But rather than exploring the region's complex history and different ethnicities, western academia focused on the Russian state and nation.

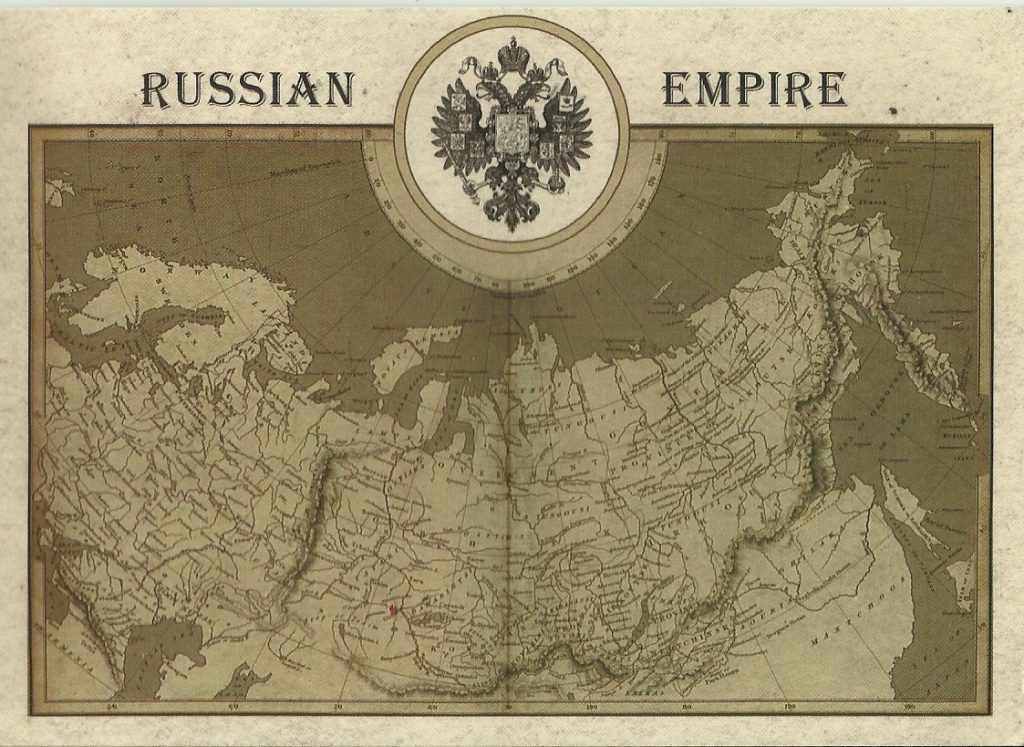

This approach by Western academics had its roots in the state-centric perspective of the 19th century when tsarist Russia represented the only Slavic empire in the world.

Apart from a general lack of interest in untangling the complexities of this multicultural empire, this approach was reinforced by Russian emigrés lecturing at Western universities, promoting Moscow-centrism in their courses.

As a result, the Western public came to see Russia, with its colonies and conquests in the Caucasus, Siberia, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe, as a clearly delineated state set in its “natural boundaries” – more akin to the ethnically based borders of Italy or France – rather than an array of colonies.

This view relates to the phenomenon of a “saltwater fallacy.” At the time, a colony was understood as an overseas holding. A territory connected to its colonizer by land mass did not qualify, even though the indigenous people experienced the same exploitation.

Western academia and elites came to acknowledge the sovereignty of Russia’s imperial holdings:

“The unwritten pact seems to be that the West does not intervene in Russian symbolic politics: this ‘academic sovereignty’ stands as an extension of geopolitical spheres of influence,” Korablyova comments.

The US policy towards the Eastern European region in the 20th century follows this thinking.

During the First World War, US President Woodrow Wilson, remembered as an advocate for Europe’s subjugated peoples, argued for the independence of only three nations of the Russian Empire – the Poles, Finns, and Armenians. He described the rest simply as “Russian territories” that needed to be liberated from the occupying Central Powers.

As the Russian Civil War began, the United States gave hope to democratic forces within the White Movement rather than to newly developing nation-states. Wilson argued that the Russian people had a right to decide their own future, paying little heed to the opinions of their non-Russian subjects.

Even as the post-Great War borders were being drawn, Wilson was reluctant to recognize the eastern Polish border and opposed the cessation of Bessarabia from Russia to Romania.

The creation of the USSR changed little from the Western perspective. The new state was seen merely as a continuation of the tsarist empire, ignoring even the administrative divisions between the Soviet republics.

The Axis invasion of the Soviet Union was perceived as a repetition of the German-Russian clash in the First World War. The West saw the anti-Soviet forces of Ukrainians and the Baltic nations purely as collaborators, undermining the Allied war efforts.

Orientalism reanimated: colonial thinking in Western analysts’ comments on Ukraine

“The old equation that all who were not pro-Communist, were pro-Nazi, was repeated,” Slavic Studies professor Clarence Manning wrote in 1957.

“Such emphasis on the Russian character of the USS.R. was furthered by many of the Russian emigres, who at the height of the war, were only too ready, whatever their political convictions, to serve the cause of Mother Russia, a policy which was fostered by Stalin’s clever use of Russian slogans.”

Even as the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Soviet republics became official members of the United Nations after the war, the USSR continued to be equated with Russia throughout the Cold War. This was reinforced by Moscow’s Russification policies, albeit in different shapes under different leaders.

And when America’s arch-rival began to dissolve in 1991, Washington reacted with anxiety rather than exaltation. In the infamous “Chicken Kyiv” speech at the Ukrainian parliament, US President George W.H. Bush warned Ukrainians about the dangers of independence.

Western policy-makers feared the sway of new nations springing up in the ruins of the Soviet empire. Many of the newly independent nations were unfamiliar and, therefore, unpredictable.

As a result, even separatist movements within the Russian Federation itself found little sympathy in the West.

In 1995, the US State Department compared Chechen independence fighters to the Confederacy in the American Civil War and Boris Yeltsin to Abraham Lincoln. Ergo, Chechens were rebels fighting against their legitimate government rather than colonized people fighting for independence.

We can still observe echoes of this perspective in the current discussion on Russia's decolonization.

The fear of the consequences of Russia’s total defeat, humiliation, and possible disintegration, is nothing new, as it follows the centuries-long school of thought permeating from university lecture halls to political and diplomatic circles.

But there seems to be light at the end of the tunnel. Recent events like the 2013 Euromaidan Revolution and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine inspired a shift among scholars, promising a new perspective among a fresh generation of decision-makers.

Spring of Ukrainian studies

While the Cold War period was dominated by Russo-centrism, it also inspired some Western academics to look at non-Russian nations of the Soviet Union, for example, Ukraine.

As a result, this era laid the ground for Ukrainian studies as an independent subject in Western universities.

In 1973, Harvard opened its Ukrainian Research Institute, the first Western academic institution wholly devoted to Ukrainian studies.

Canada became an important center for researching the subject, among others, thanks to the Ukrainian emigres arriving during the 1950s and a strong local Ukrainian community. The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta opened in 1976 as the second Western institution devoted to the subject.

The first cracks in the Soviet dominion in 1989 provided a fresh incentive for interest in Ukraine. The year saw the establishment of the International Association of Ukrainian Studies in Naples, coordinating research on Ukraine’s culture, history, and language abroad.

The interest in Ukrainian studies was not without pragmatic reasons – some in the West hoped that non-Russian nations of the USSR could become allies against Moscow.

Nevertheless, this line of thought remained second to the perpetual hopes of democratizing the Russian nation itself. Resources invested in Russian studies were considerably larger than those of non-Russian Eastern European nations.

Ukrainian studies also could not compete

with the Russia-oriented courses in terms of number of students.

The re-emergence of Ukraine as an independent nation in 1991 did little to change these trends.

Consequently, the topic of Ukraine remained shrouded in mystery among Western leadership. The after-effects of Soviet-era Russification of Ukraine and the country's bilingual nature only added to the confusion.

Even in 2014, Germany’s ex-chancellor Helmut Schmidt declared that “historians still doubt the very existence of the Ukrainian nation.”

Ukraine challenged this Moscow-centric perspective when it sought to escape Russia’s sphere of influence through the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2013-14 Euromaidan Revolution.

“Unpredicted developments that surprised external observers in 2004, and in 2014, put Ukraine on their mental maps, with a steep rise of interest every time, fading away eventually,” Korablyova says.

Only the full-scale invasion of 2022 became the true turning point. The full-scale war challenged the preconceptions of the Western elites about the Eastern European region.

Ukrainians put themselves resolutely in opposition to Russia, and therefore to the narrative about the Russian historical, cultural, and political hegemony in the region.

“What was different with the full-scale invasion was that, this time, it was more than [Western] curiosity. It was an epistemological crisis that exposed the failure of East European studies to predict and plausibly explain the behavior of all the main actors involved.

“It opened a window of opportunity for Ukraine to speak for itself on global stages,” Korablyova says.

Western academia began to reassess its discourse on Eastern Europe:

- Cambridge University launched a series of lectures in 2022 on rethinking Slavonic Studies, examining the Russian imperial legacy in the histories of other Slavic nations.

- In the fall of 2023, the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies will host a conference in Philadelphia on “de-colonizing” the subject.

- Scholars call for abandoning concepts like “Eurasian Studies” or “Post-Soviet space” in academia because they lump together diverse ethnicities and cultures simply because of their shared history of Russian domination.

There is still much work to be done, however. According to Korablyova, even though Ukrainian voices have won the recognition of their agency, they are still not treated as equal.

Western scientific knowledge, built upon Western historical experience and Western research, is still treated as a universally applicable norm, even when observing non-western nations.

To achieve real change, Eastern European perspectives must be treated as equal and allowed to contribute to the universal body of knowledge.

Old entrenched perspectives constructed by hegemonic powers on “minor nations” must be thoroughly reassessed.

Other marginalized voices must be included in the conversation, not only Ukrainians, but also other nations with a history of Russian domination and those currently under Moscow’s rule.

Just as Moscow-centrism inspired Western policy of the 20th century, so can Ukrainian studies and its equivalents for other “minor” nations inspire change in the halls of power.

They can help to foster a new generation of decision-makers not exposed to the whitewashing of the Russian imperial project.

Related:

- Orientalism reanimated: colonial thinking in Western analysts’ comments on Ukraine

- Why Russia must be decolonized

- Ukraine adopts law that condemns Russian Imperial policy and decolonizes toponyms

- National minorities of Russia call to decolonize, denuclearize “imperial, terrorist” Russian state

- The myth of “historically Russian Crimea”: colonialism, deconstructed

- Westsplaining Ukraine