Dekulakization was carried out by OGPU detachments (Soviet secret police from 1922 to 1934) led by “party commissioners sent from Moscow” with the active collaboration of local lumpen scum and party leaders - in accordance with Stalin’s plan to “eliminate the kulaks as a class” and the resolution of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU(b) of January 30, 1930.

On January 30, 1930, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU(b) issued a Resolution ‘On measures for the liquidation of kulak property’, which launched widespread repressions against peasants and small landowners, a process known as ‘dekulakization’.

The Resolution formally enshrined Stalin’s directives, voiced by the Soviet leader on January 21, 1930 in his appeal ‘On the policy of liquidation of the kulaks as a class’.

“In order to eliminate the kulaks as a class, it is necessary to openly break their spirit and resistance, and deprive them of the sources for further existence and development. The party’s current policy in the towns and villages marks a new procedure for eliminating the kulaks as a class,”

said Joseph Stalin, secretary general of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR.

Stalin’s first objective was to rid society of the peasantry, which concealed ‘capitalist elements (kulaks)’, and was thus irrevocably hostile to the regime. Dekulakization consisted in expropriation, eviction of entire families, deportation of millions of farmers, and, in the event of resistance, physical annihilation.

This Resolution defined dekulakization quotas, i.e. first and second categories for each region or republic of the Soviet Union. The first category kulaks, defined as ‘activists, engaged in counter-revolutionary activities’, were to be arrested and sent to labour camps after a brief appearance before the so-called judicial ‘troika’. The most ‘dangerous’ activists were to be sentenced to death while second-category kulaks, defined as ‘exploiters, but less actively engaged in counter-revolutionary activities’, were to be deported to distant Siberian regions. Dispossessed, deprived of their civic rights, deported, exiled to remote areas of the USSR, these kulak families were assigned to ‘special villages’ run by the OGPU (NKVD as of 1934).

Hundreds of thousands of families lost their means of subsistence. They were scattered across the Soviet country: some were deported to Siberia, some fled to the Donbas, some were sent to dig the White Sea Canal, some were imprisoned, some were executed, and small children were taken to orphanages.

In January 2020 (90th commemoration of the total extermination of private property in the USSR), Radio Liberty and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide launched a special project – ‘Dekulakization: how the Stalinist regime destroyed Ukraine’s free peasant class’. Hundreds of testimonies about dispossessed and persecuted families have been sent to Radio Liberty’s editorial office and been reprinted online.

Here are a few more narratives describing the horrifying events of 1932-33 in Ukraine…

Tetiana Ponomarenko

I’d really love to find some descendants of Nikon Ivanovych Porokh, who until 1930 lived in the village of Nove Mazhorove, Kostiantynohradsky Raion, Poltava Oblast (today, Zachepylivsky Raion, Kharkiv Oblast).

My great-grandfather Nikon Porokh and his family of seven children were totally dispossessed and deported; they were prohibited from coming back to their homeland. His eldest daughter, my grandmother, was left behind because she already had a family and lived separately.

My grandmother’s younger brother, 17-year-old Fedir, was accused of taking part in the anti-Soviet uprising and deported to Siberia, where he spent 17 years. He returned to Ukraine in 1947, but only after Stalin’s death was he able to come and visit his sister.

We don’t know what happened to my grandmother’s other sisters and brothers. Maybe someone survived…

Irena Synkevych

My father told me the story of his family shortly before his death in the 1990s, when Ukraine became independent. Until then, neither my father nor my mother ever spoke of the past, because it was very difficult for them to talk about my father’s childhood, the hunger and his life as an orphan.

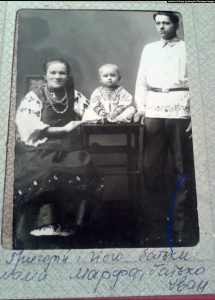

My father Hryhoriy was born in a prosperous peasant family in 1928 in Sumy Oblast, in the village of Popivka, Konotopsky Raion. My father’s mother, Marfa Suprun, was the eighth child, the youngest in Anton Suprun’s large family. After marrying Ivan Malenko, she continued living with her parents.

All the older brothers were well educated and lived separately from the patriarchal home.

One of the brothers was an aviator; he knew Ihor Sikorsky, and may have even worked with him. Another brother was a railway engineer, and yet another was an officer. My father didn’t tell us anything about the others.

My grandfather had a big house with eight rooms and a lot of land. Dekulakization began in 1930, when my father was 2 ½ years old and his sister Antonina was five.

Everyone was taken away in one night. There were loud cries, weeping and shouting as the family was forced brutally from their home. The children were left with the neighbours, who then handed them over to distant relatives. It was thanks to such family solidarity that the children survived.

The adult “children” (my father and his sister) first met in the late 1950s, when they were 25-30 years old. Antonina had been adopted by another family. We don’t know their names. She was married and became Omelchenko.

My father was an orphan at the age of 2. He suffered from hunger and cold, but, thanks to God and those distant relatives, he survived.

At the age of 13, he began working in an aircraft maintenance workshop and was allowed to live there. The other workers named him “the regiment’s pet”. He worked very hard, lifting heavy machine parts and repairing aircraft.

Father went through World War II with that air regiment - all the way to Budapest, served in the army, returned and remained in Western Ukraine.

He studied, worked as an editor of a district newspaper, and got married. Four children were born, followed by grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1958, my parents visited his native village of Popivka. He showed my mother his family home, which is now used by the village council.

Many villagers recognized him and those who were involved in the dekulakization process wrote a collective letter to the regional party committee, denouncing “the kulak’s grandson who now lives in the western region of Ukraine”. It was still 1958…

My father was summoned by the secretary of the party’s regional committee. Actually, he turned out to be a fairly decent man, showed my father the letter, tore it up and burnt it, saying that “now only the two of us know about it”.

To this day, we don’t know where the other members of the family are. Before his death in 1996, my father said that everyone had been deported to Norilsk [Krasnoyarsk Krai, RF-Ed], where they all disappeared. We don’t know if anyone escaped. We also don’t know whether any of my father’s uncles who had families survived.

But, I really want to believe that somewhere in the world there is someone from the large family of Anton Suprun from the village of Popivka, Konotopsky Raion, Sumy Oblast.

Tetyana Chviruk

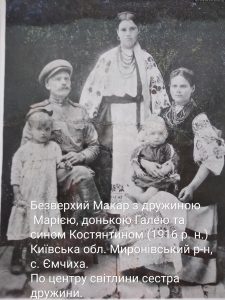

My father Kostiantyn Makarovych Bezverkhy (June 21, 1916 - November 18, 1974) was born in the village of Yemchykha, Myronivsky Raion, Kyiv Oblast.

His father, and my grandfather Makar Viktorovych Bezverkhy, fled the NKVD and dekulakization with his three children (his wife Mariya had died earlier) to the town of Kostiantynivka, Donetsk Oblast. He left his land, his house, all his property behind…

Anhelina Kolisnichenko

I’m the fourth generation in my family, so I have little information about this period. During the Soviet regime, no one spoke about this; it was a taboo subject. Unfortunately, my grandmother, who remembered those events, died in 1985.

My mother came from the village of Makiyivka, Smiliansky Raion, Cherkasy Oblast. I read somewhere that the village was founded by Kozaks (Cossacks), so most of the peasants are of Cossack descent. My great-grandfather Pylyp Parashchenko owned land there; there were several other landowners like him.

We can’t really call him a “wealthy landowner”, because he and his family worked very hard. But, he hired people during the harvesting season.

My great-grandmother told us that he paid his workers well. And, it was probably true, because our family was well respected in the village.

In the 1930s, the communists arrived and began forcing the people to join their collective farms. I don’t know if anyone actually resisted, but I know that great-grandfather Pylyp fled the Soviets, and no one ever saw him again.

We still don’t know what happened to him. He just disappeared.

The land was confiscated, and as they couldn’t find my great-grandfather Pylyp, they arrested his son, Vasyl Pylypovych Parashchenko. He served two years and returned to the village.

At that time, Pylyp’s wife and child - my great-grandmother and the older sister of my yet unborn grandmother - moved from the centre to the very edge of the village. They were forced to find shelter elsewhere as the family home was looted and the iron roof was dismantled to cover the village council building.

So, with the help of some good people, they built a simple earthen house. That house was struck by lightning several times, and once it even burnt to the ground. Everyone got together and another house was built. I remember it well… it was my place in paradise.

Great-grandfather’s son Vasyl, “the kulak’s son”, who had just returned from prison in 1939, was among the first to be sent to the front in 1941. My great-grandmother told us that she almost immediately received news that he was missing. So, both my great-grandfather and his son went missing; we still don’t know where they lie and who buried them.

Until her retirement, my great-grandmother worked on the Soviet collective farm that had taken over her land.

Liubov Zhelizniak

My great-grandfather Petro Nykyforovych Maksymeiko had approximately ten hectares of land purchased during the Stolypin reform in the village of Remivka, Lubensky Raion, Poltava Oblast. He grew sugar beets. When the Bolsheviks came, my great-grandfather flatly refused to join the collective farm. He was arrested in 1930.

Great-grandfather was sent to work on the White Sea Canal [built in 21 months mostly manually by prisoners of Stalin’s Gulag concentration camps. It was inaugurated in 1933, and connected the White Sea in the Arctic Ocean, with Lake Onega, which is further connected to the Baltic Sea- Ed)]

His wife and five children were evicted from their home and their property confiscated. They moved out of the village and lived in a small, dark dugout.

My great-grandfather survived those difficult years, but returned home in the early summer of 1933 with a damaged liver and a severe form of pulmonary tuberculosis. He died a month later. He was only 47 years old.

As part of a joint project with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide - ‘Dekulakization: how the Stalinist regime destroyed Ukraine’s free peasant class’ - Radio Liberty asks families who know about their relatives being dekulakized to write and recount their stories. Important information to be included: names and surnames, age, number of family members and years of birth, children, place of residence (village, district, region), possessions (land, livestock, equipment, property), social status, hired workers, etc., as well as how they experienced and survived dekulakization. Facts, reactions and feelings are important. Please send all available photos and documents.

Please write to: [email protected]

TO BE CONTINUED…