They were careful to manage the image of the USSR abroad after the 1921-23 famine that was a PR catastrophe for the Bolshevik government. Then, the burgeoning Soviet state accepted the aid of foreign humanitarian agencies in return for their freedom to operate, as a result of which the world saw the full extent of the human misery on Soviet soil. Censorship and broad restrictions made documentation and reporting of facts challenging; nevertheless, some photos did leak out from behind the Soviet border.

The most famous ones were made by the Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger.

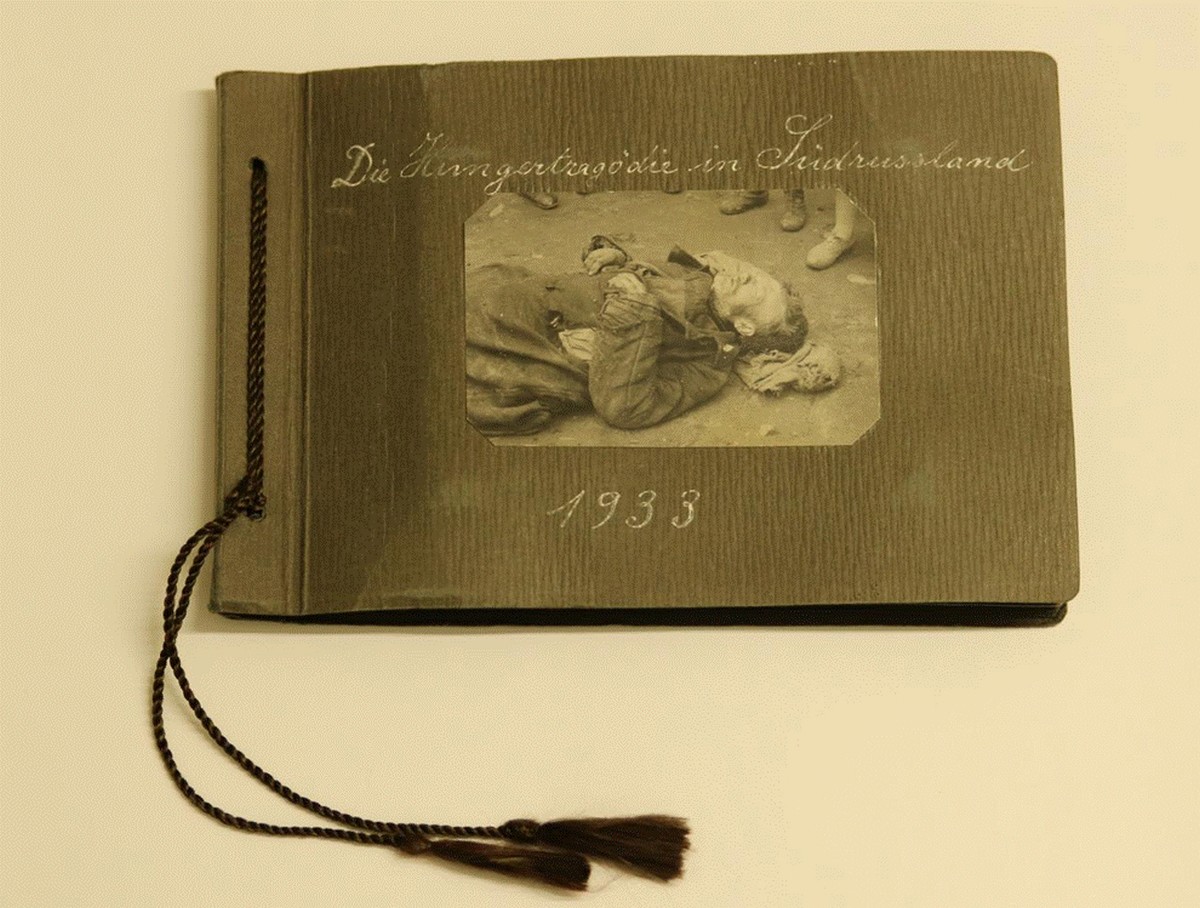

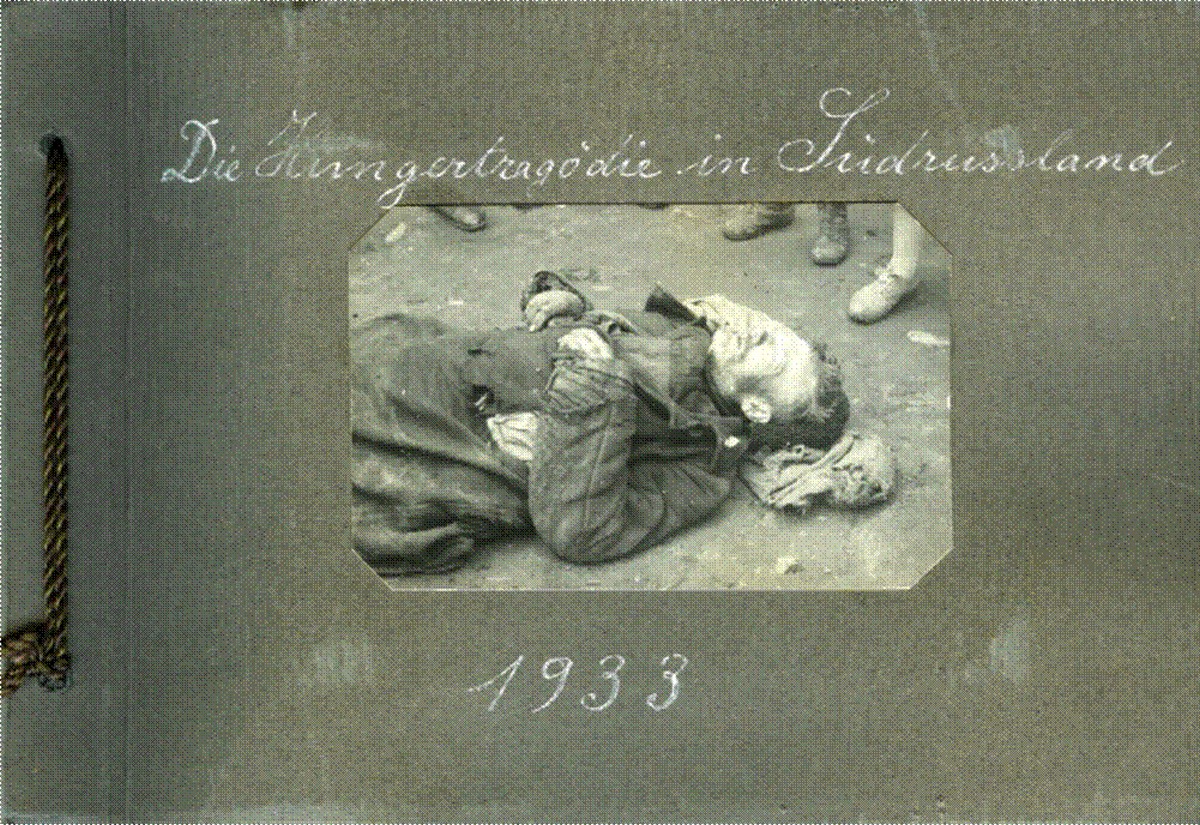

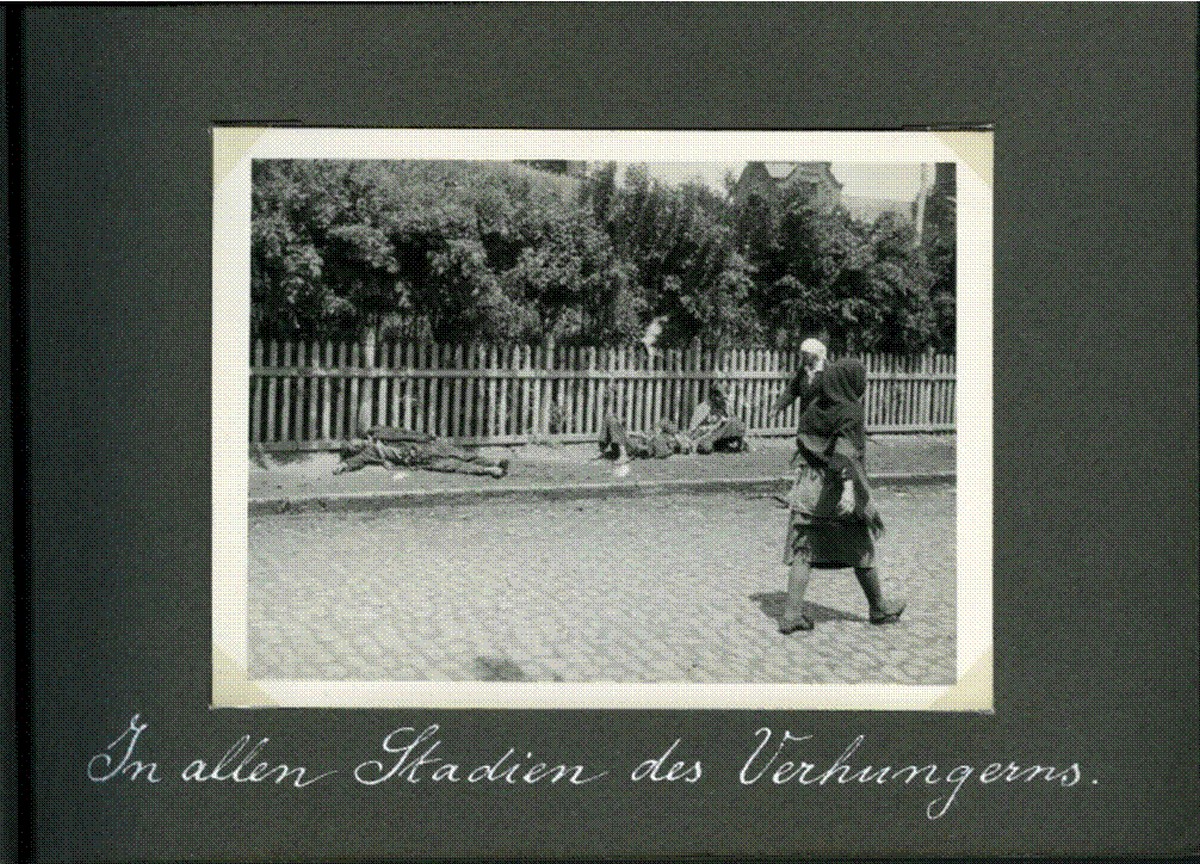

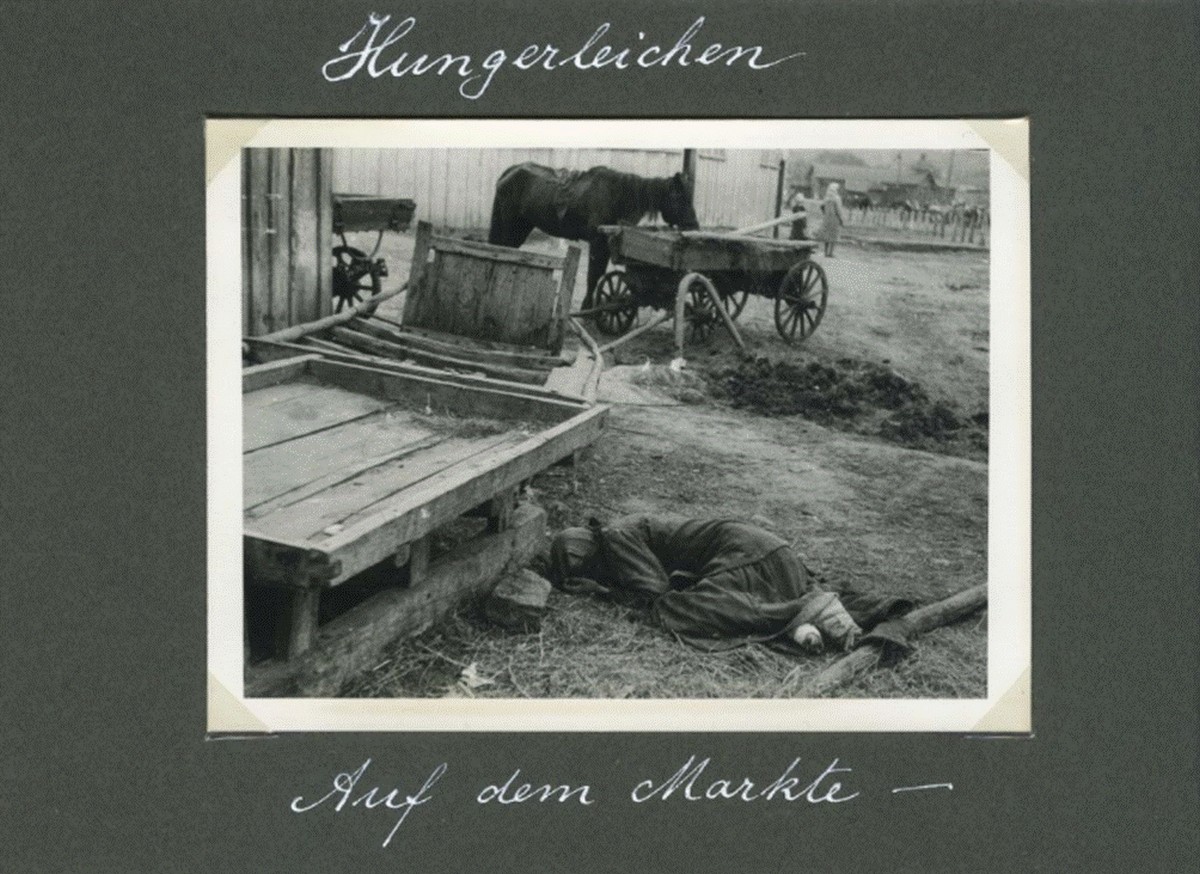

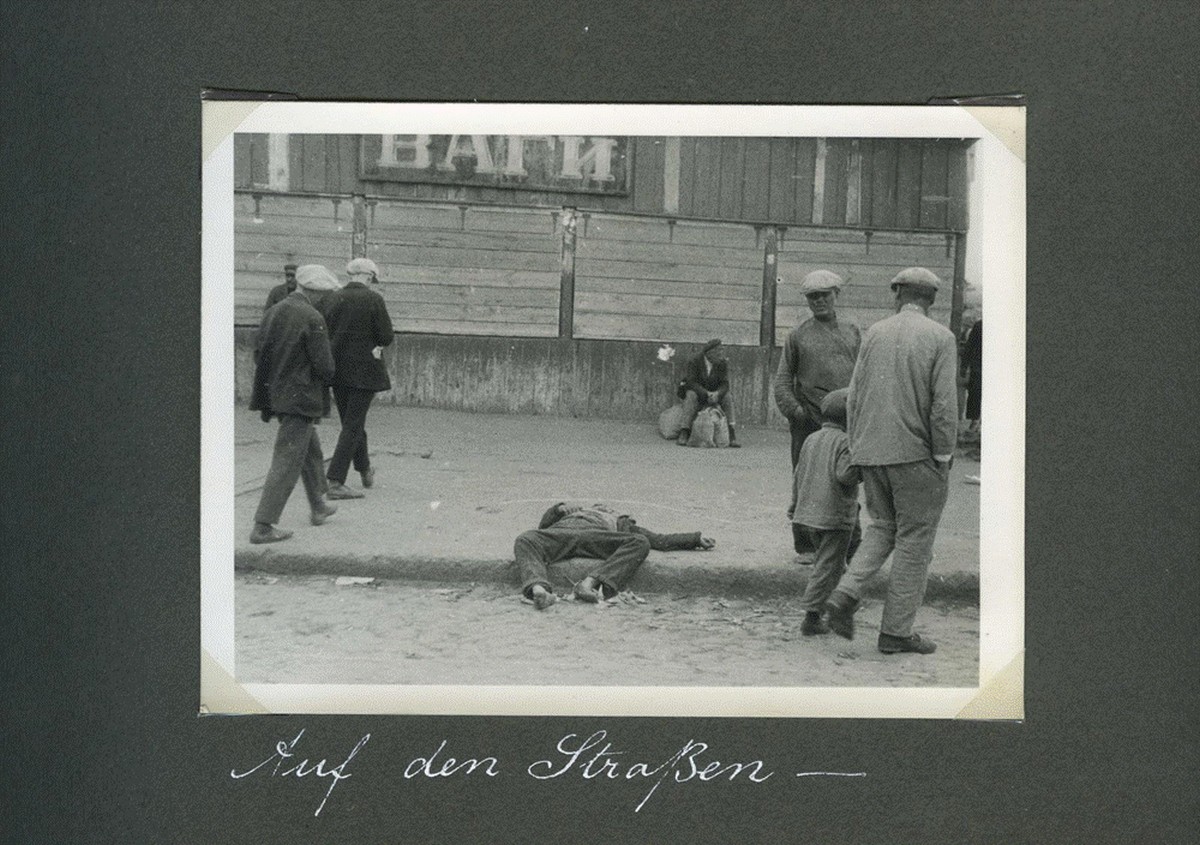

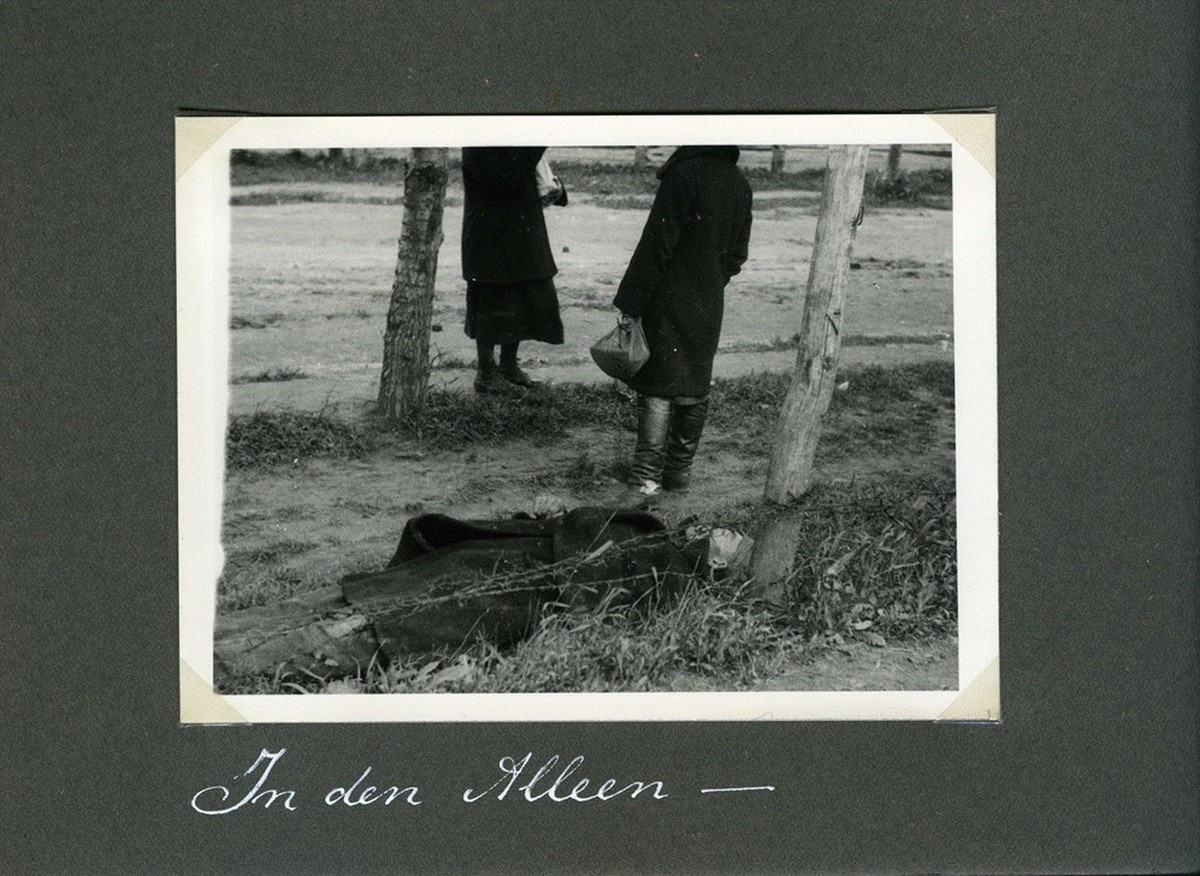

Here we present his Innitzer album, the popular name of an album of photographs that were taken by Wienerberger in 1933 while he was working as a managing consultant in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s capital at that time.

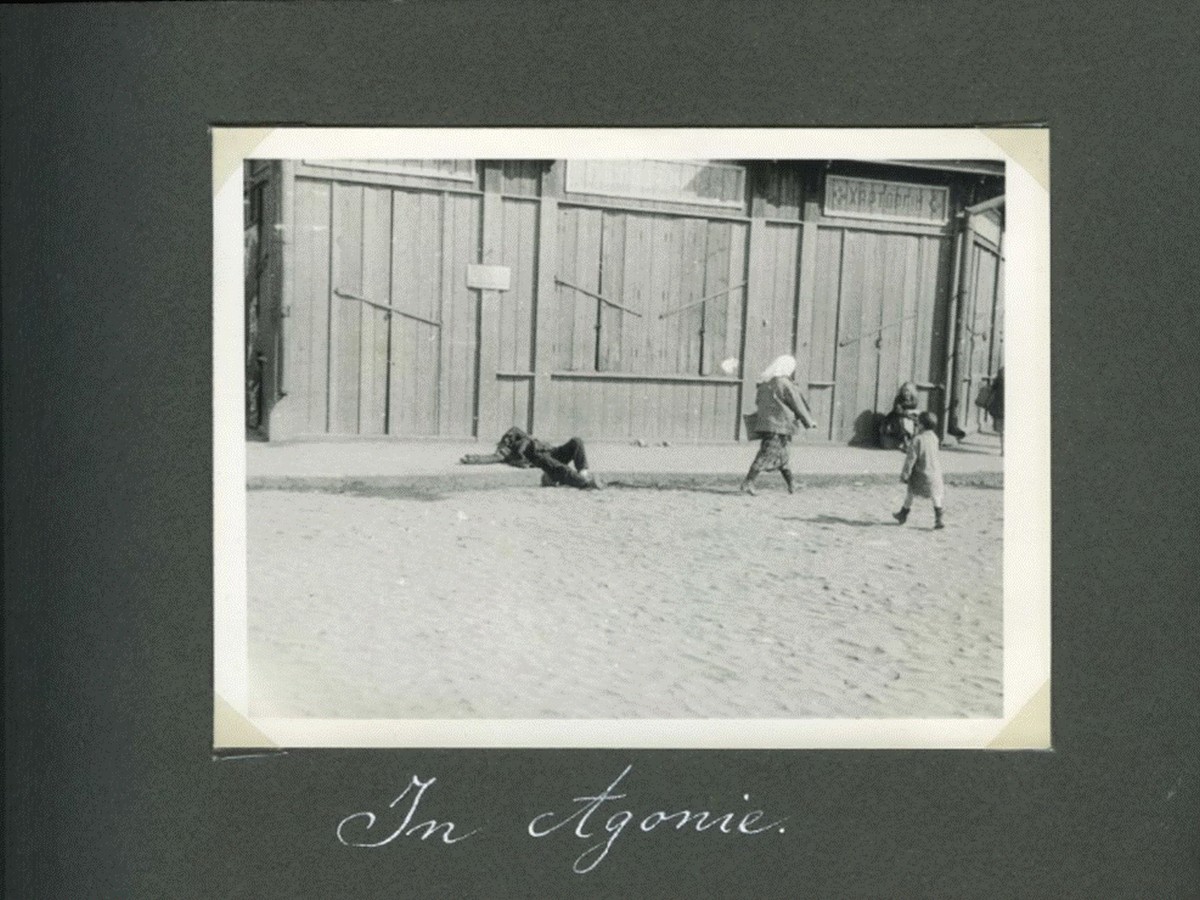

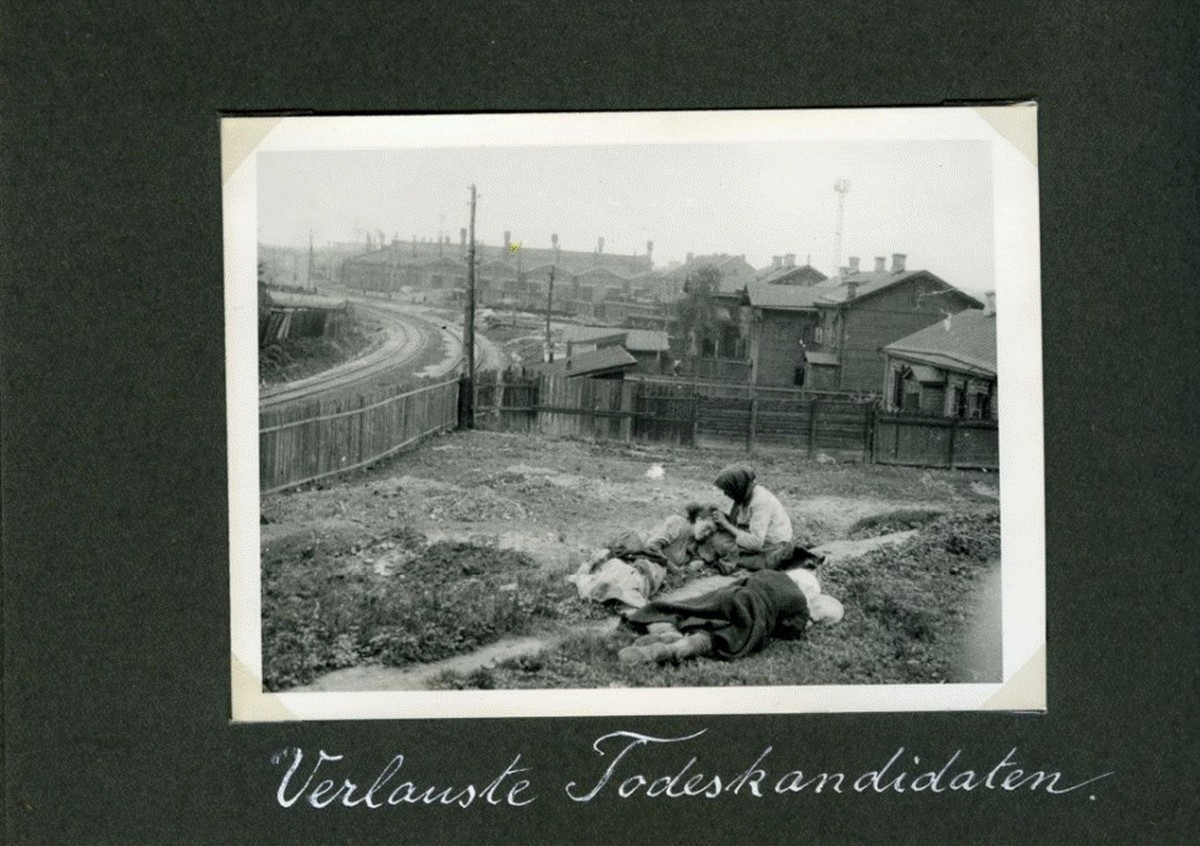

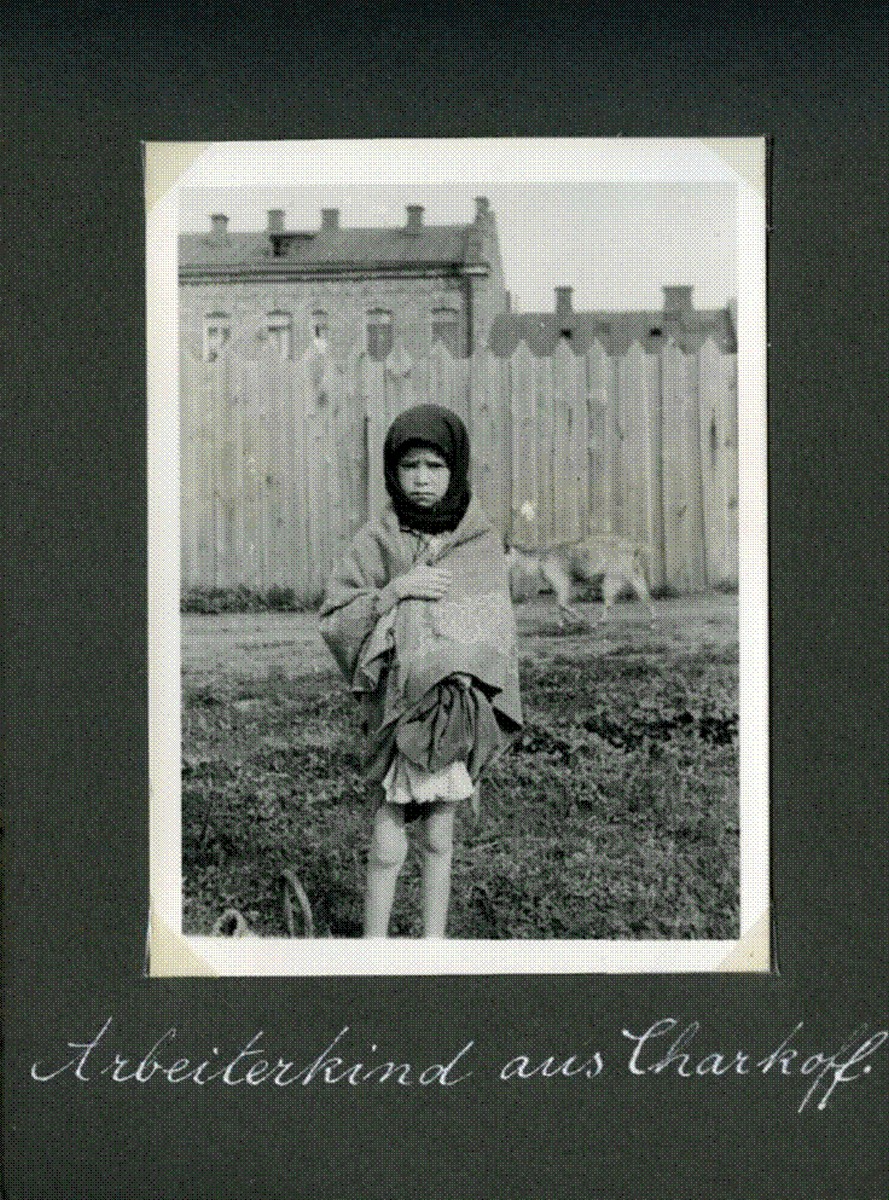

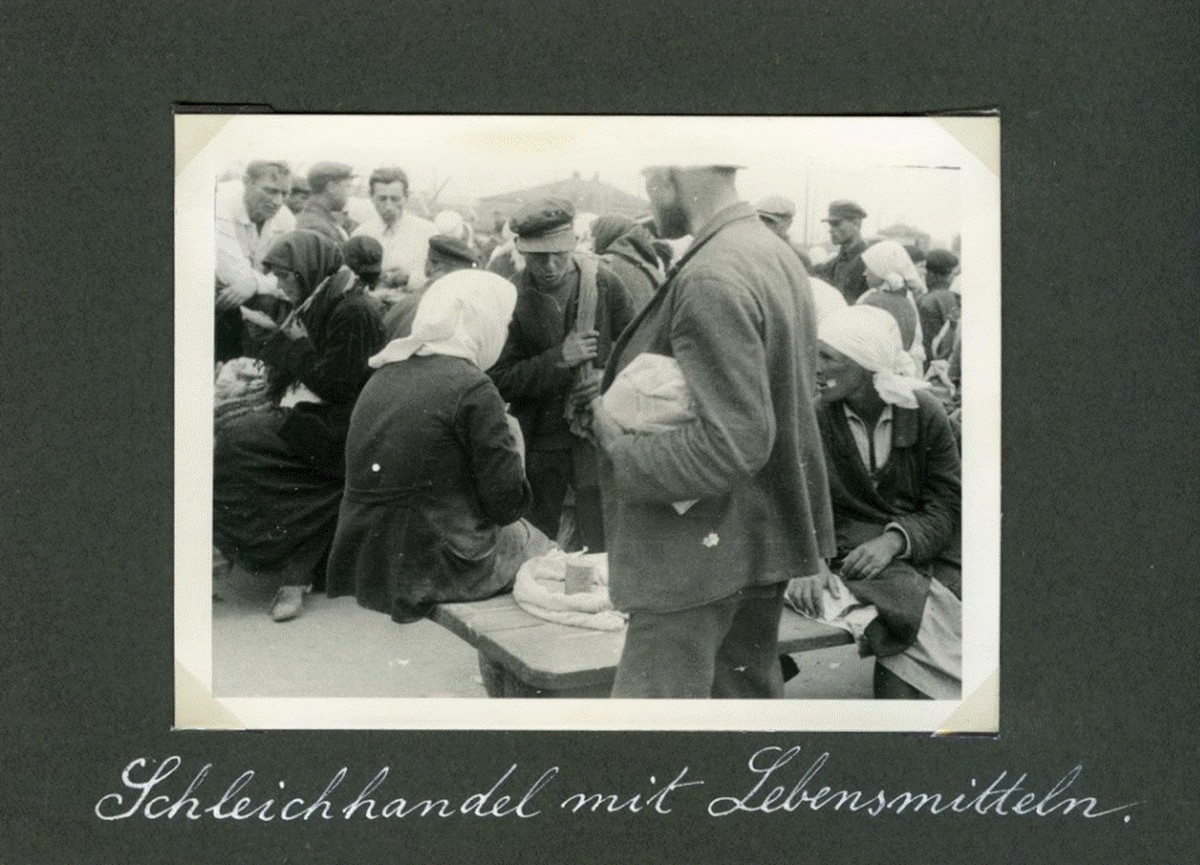

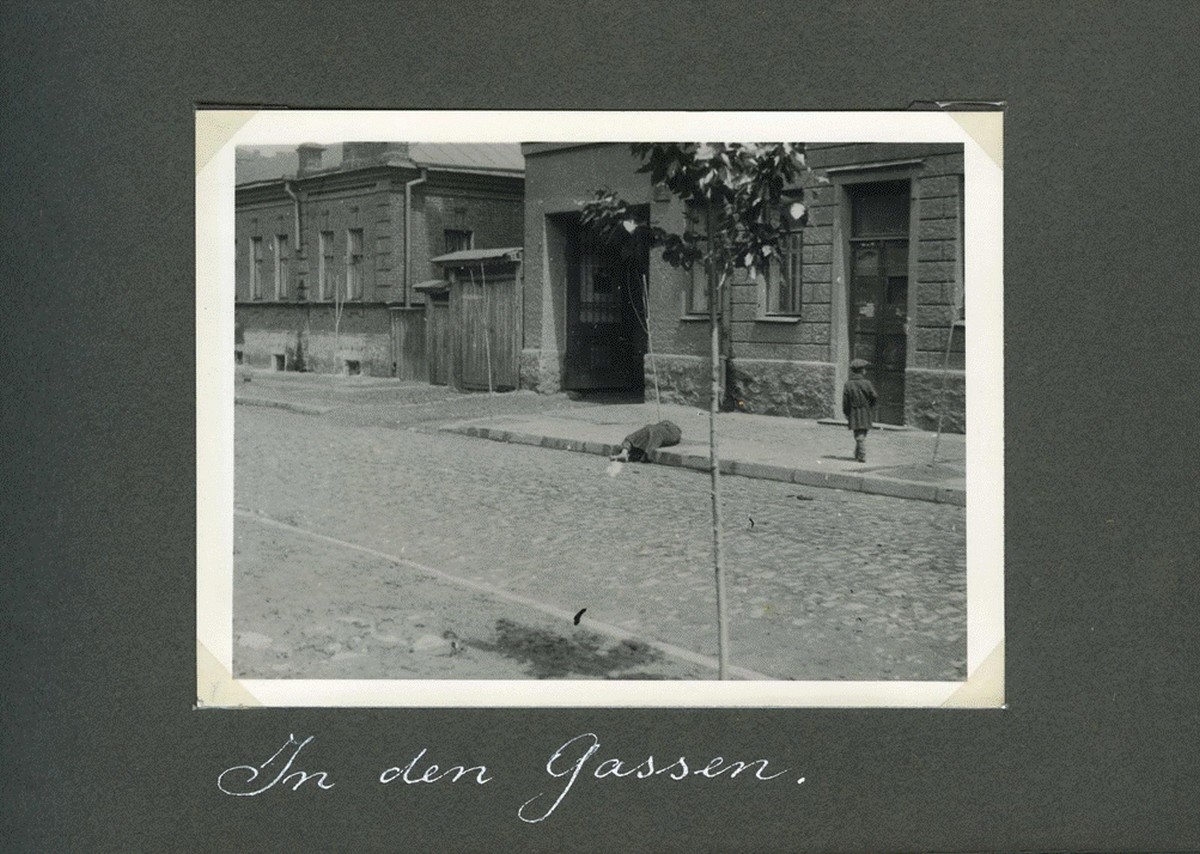

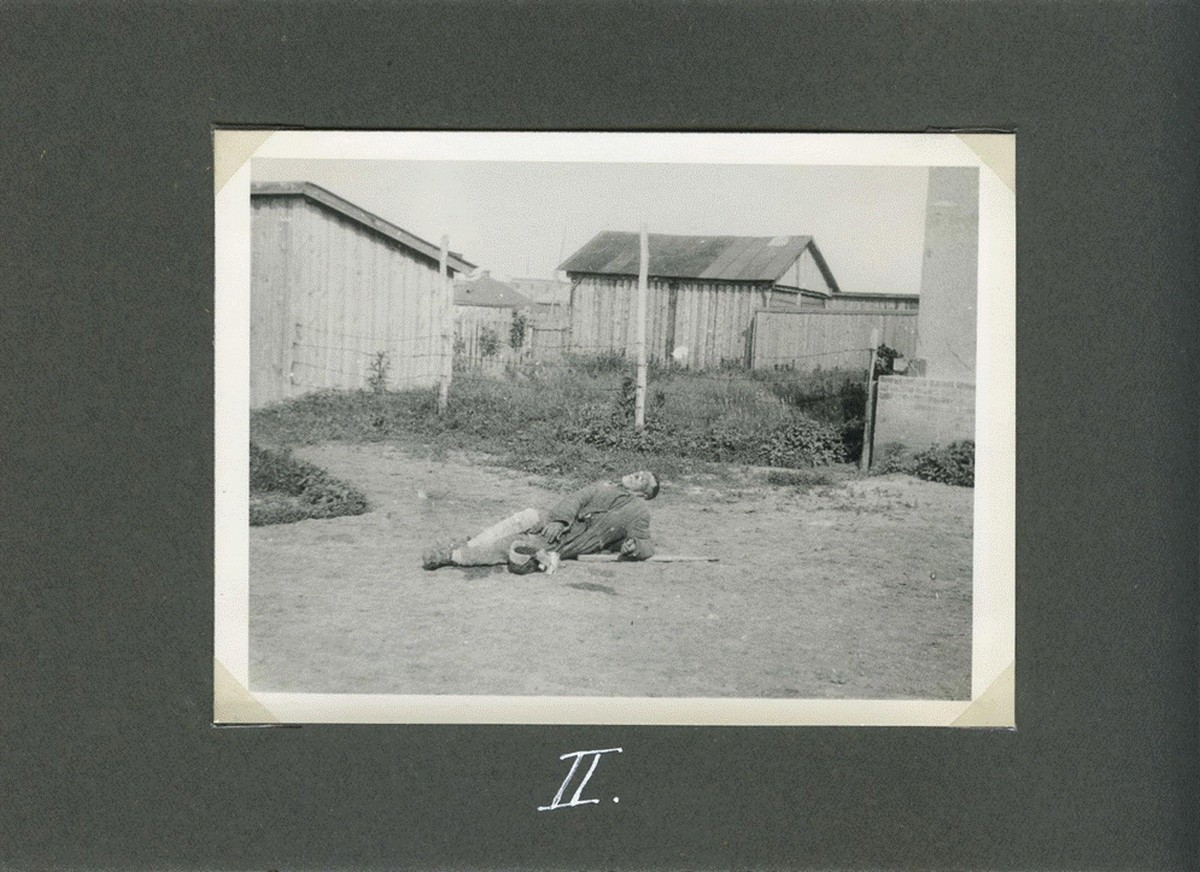

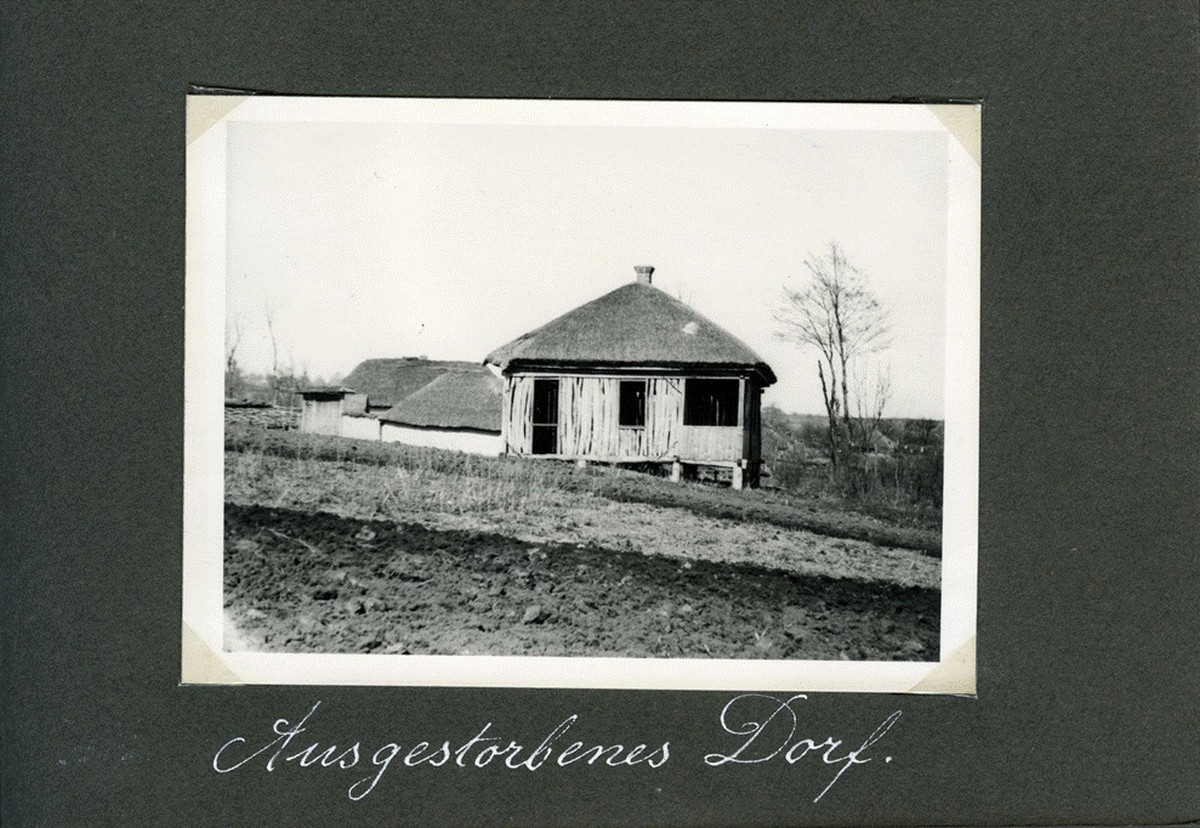

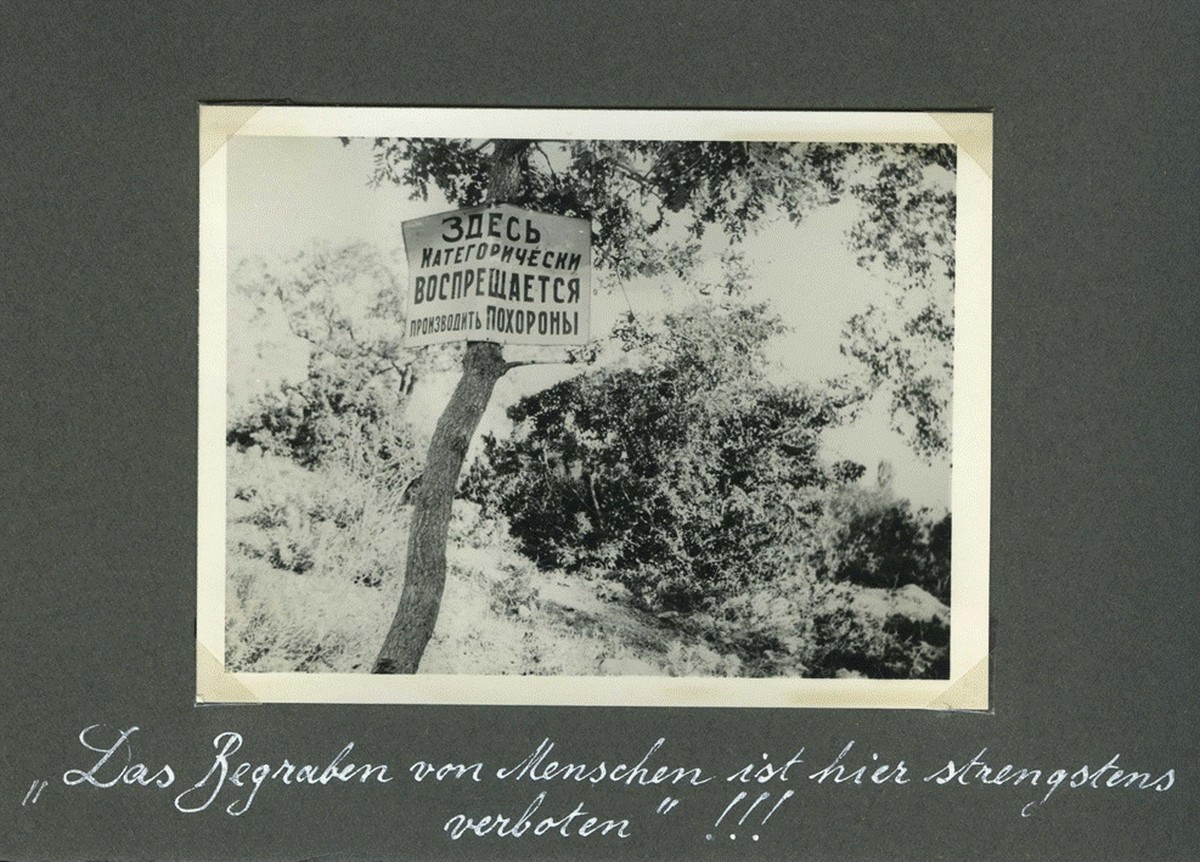

The photographs depict starving residents from the rural heartland of Ukraine flocking to Kharkiv on foot; the endless lines of city residents waiting to buy their meager ration of food; the homeless rural residents – young and old alike, struggling to survive and dying in the city’s streets, hastily dug mass graves just outside the city.

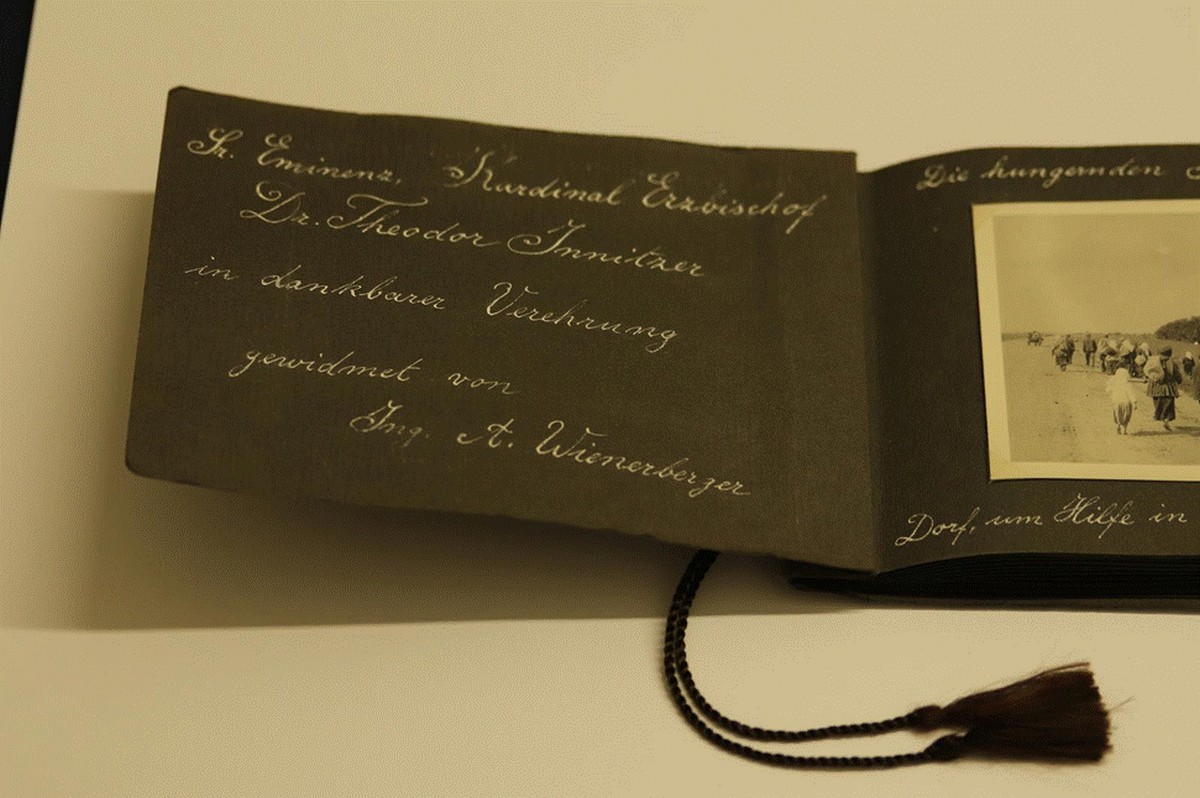

In September 1933, Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna, the presiding Roman Catholic archbishop in Austria at that time had established a widely publicized interfaith humanitarian relief committee to provide aid to the starving in Soviet Ukraine and the German colonies in Russia. The Soviet government in Moscow, however, emphatically denied the existence of famine, and the committee’s offers of assistance were refused.

When Wienerberger returned to Austria in 1934, he compiled a set of 25 photographs into an album he titled Die Hungertragödie in Südrussland 1933 [The Tragedy of Famine in South Russia, 1933]. He wrote a brief dedication statement with his signature on the back of the album cover and presented it as a gift of respect and gratitude to Cardinal Innitzer for his efforts. The album remains to this day in the Diocesan Archive in Vienna.

Alexander Wienerberger took his photos during the spring and summer of 1933, and many were specific to a district of the city known as “Kholodna Hora” (“Cold Mountain”), or as Wienerberger referred to it in his native German, “Kalten Berg,” where the factory that he managed was located.

Innitzer album dedication page. This statement appears on the inside of the front cover to an album with the title: Die Hungertragödie in Südrussland 1933 [The Tragedy of Famine in South Russia 1933.] Also known as “The Innitzer album,” it is a pocket sized album of photographs that the Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger had taken while he was working as a consultant in Kharkiv in 1933. The dedication reads: “[dedicated to His eminence, Cardinal Archbishop Dr. Theodor Innitzer with grateful respect, from Engineer A. Wienerberger." Source.

.

.

.

Read also:

- Engineer Wienerberger’s unknown photographs of the Holodomor

- Ukrainian Holodomor Museum launches crowdfunding campaign to create main exhibition

- Holodomor survivor stories come to life in mobile app for tourists

- Bread from tree bark and straw: students launch online “restaurant” with Holodomor “recipes”

- Stalin’s anti-Ukrainian policies in RSFSR prove Holodomor was a genocide

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors