Decentralization has breathed new life into stagnant Ukrainian villages, which now have incentives to spur their own development to use their own tax money. Remarkably, the success of the reform has generated controversy: some villages are so successful that they are reluctant to be adjoined to cities despite governmental plans.

After Russia fostered a war in eastern Ukraine, doctor Kostiantyn Kolomiyets fled with his family northward. He settled in Chernihiv Oblast together with many other internally displaced people. Like most IDPs, he struggled to find a good job, searching for a medical position in Chernihiv, the regional center.

What happened next would have been unthinkable five years ago. He finally found a job - not in the city, but Kiptiv village, where a new medical center was opened thanks to the decentralization reform launched after 2014.

"It is very good that this new hospital opened. There is a person we can call. You can receive needed infusions here, medicines will be prescribed, and the pharmacy works here. And the doctors who came are good. The village council cares for us," Hanna Haniailo, a Kiptiv resident, told Euromaidan Press.

Since Ukraine’s independence in 1991, villages throughout the country have mostly stagnated. Especially in Chernihiv Oblast, villagers moved out in droves, leading to the eery situation of every second house on the streets of some villages being abandoned.

But now, various infrastructure projects and, in particular, medical centers not only improve living conditions in villages but also help create workplaces and rejuvenate depressed areas.

A Soviet system

As a successor of the USSR, Ukraine inherited a highly centralized system of public administration. Apart from some minor changes in 1991-1996, the system mostly remained the same: public costs were distributed from the central budget to local municipalities through the system of state subsidies, managed by regional administrations appointed jointly by the President and government. Local budgets were limited due to taxation laws that provided most of the costs to the central budget. Local councils, both village and district (rayonna rada), could define local priorities but largely depended on funding provided by the central budget.

The only exception were big and medium-sized cities that had a different model of taxation and, therefore, sufficient budget revenues.

This is ultimately the reason why Ukrainian cities could provide more or less normal living conditions while villages and small towns were constantly stagnating since 1991.

Local farms and businesses weren’t developing due to a lack of institutional and real infrastructure in rural areas. Hence most Ukrainian labor migrants came from villages.

The decentralization reform launched in 2014 changed the situation dramatically and many local municipalities started collecting larger budget revenues per capita than large cities. This has created [highlight]a new and unexpected phenomenon in Ukraine where many villages oppose proposed unification with cities since they can now operate better by themselves.

The transition period ends this year, in 2020. So it's time to sum up how Ukraine developed with decentralization, and also to outline some controversies that have emerged during the reform. In general, while financial decentralization and new taxation laws are praised by the consensus and demonstrate obvious improvement in Ukrainian villages, expert assessments of the administrative model of the reform have been mixed.

A short history and model of the reform

Decentralization reform has been ongoing in Ukraine since 2014. The intent of the reform was to give local municipalities additional authority and tax revenues to take responsibility for the most pressing local issues, such as infrastructure, schools, parks and public spaces, cultural institutions and resources such as libraries and art schools, waste management, ecological management, and healthcare (including medical centers, facilities for general practitioners, and even maintenance of hospitals).

Essentially, municipalities were to de-facto take responsibility for all public issues, leaving the state responsible only for pensions, higher education, security and police, and medical insurance, as well as regulatory policy and norms.

Yet, in order to acquire such autonomy, municipalities had to unite into so-called [highlight]united territorial communities (OTG) to be sure they had enough territory, population, and capacity to provide all required services.

On average, 6 villages that previously had been separate municipalities with separate management, were united into one OTG of 50-100 km2, although there are cases of considerably larger OTGs. Villages typically united around the biggest village or small local town.

The process of unification was the most controversial part of the reform. Many villages or their public representatives didn’t want to lose their “sovereignty” while becoming part of the larger community. Therefore, the whole process was voluntary. Communities could merge into a OTG on the basis of mutual agreement and, subsequently, receive additional authority and tax revenues. Otherwise, they could remain a small separate village, controlling its own territory but with fewer revenues and relying on low-quality public services from regional state administration.

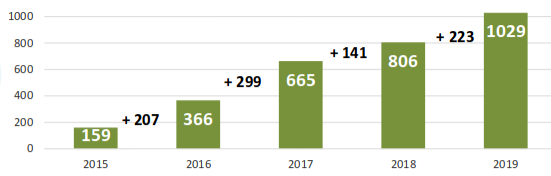

During 2014-2019, in total 1029 OTGs were created in Ukraine on the basis of voluntary agreement between villages or villages and small towns. Today OTGs cover 44.2% of government-controlled Ukrainian territory (excluding occupied Crimea and Donbas). All the rest belongs either to still unincorporated villages or bigger cities.

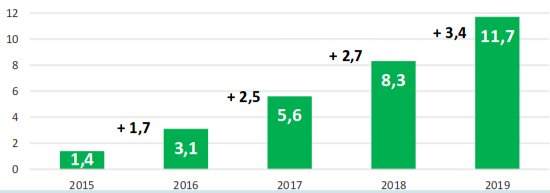

11.7 million or 1/3 of Ukrainians live in OTGs. Another 27.5% of Ukrainians still live in separate villages and small towns that haven’t formed their OTGs. The other 39.5% of Ukrainians live in cities that already had tax preferences before decentralization.

The general consequences of the reform are promising. To better explain them, one should consider separately financial and administrative decentralization.

Financial decentralization has more than doubled budgets of new local municipalities (OTGs), and other results of the reform

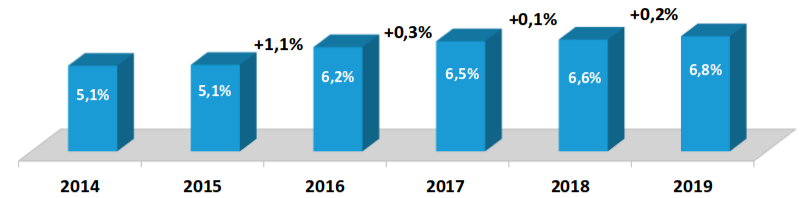

Financial decentralization means that 60% of the individual income tax and some other taxes that used to be allocated to the district (rayonnyi) or central budgets are now allocated to the budget of OTGs. Therefore, municipalities now can manage a substantial part of the costs.

Moreover, OTGs now can receive educational, medical, sport and other subsidies directly from the state and allocate them to local needs independently, which is a great improvement over the previous situation, when subsidies for villages and small towns were entirely managed by state district officials with minor participation from locals.

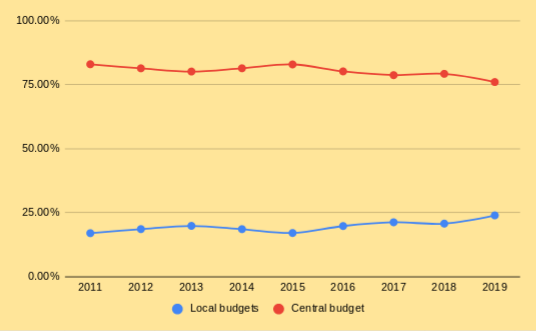

Consequently, since the beginning of fiscal decentralization, local budget revenues have been growing faster than revenues of the central budget. Partially that was achieved simply by the creation of OTGs, where a large part of taxes now remain instead of going to the central budget.

In the long-term, the local revenues grow yet more, since OTGs are now more interested in fostering local entrepreneurship and becoming more self-sufficient. The potential for development and the possibility for businesses to engage with local authorities faster also facilitates the development of OTG’s.

Financial decentralization also means that the state raises the amount of subsidies and state programs designed to promote local infrastructure, education, and sports facilities. And newly created OTGs allocate these funds more effectively, as they have a better understanding of local needs. The rules of competition between OTGs for particular state subsidies also facilitates their development.

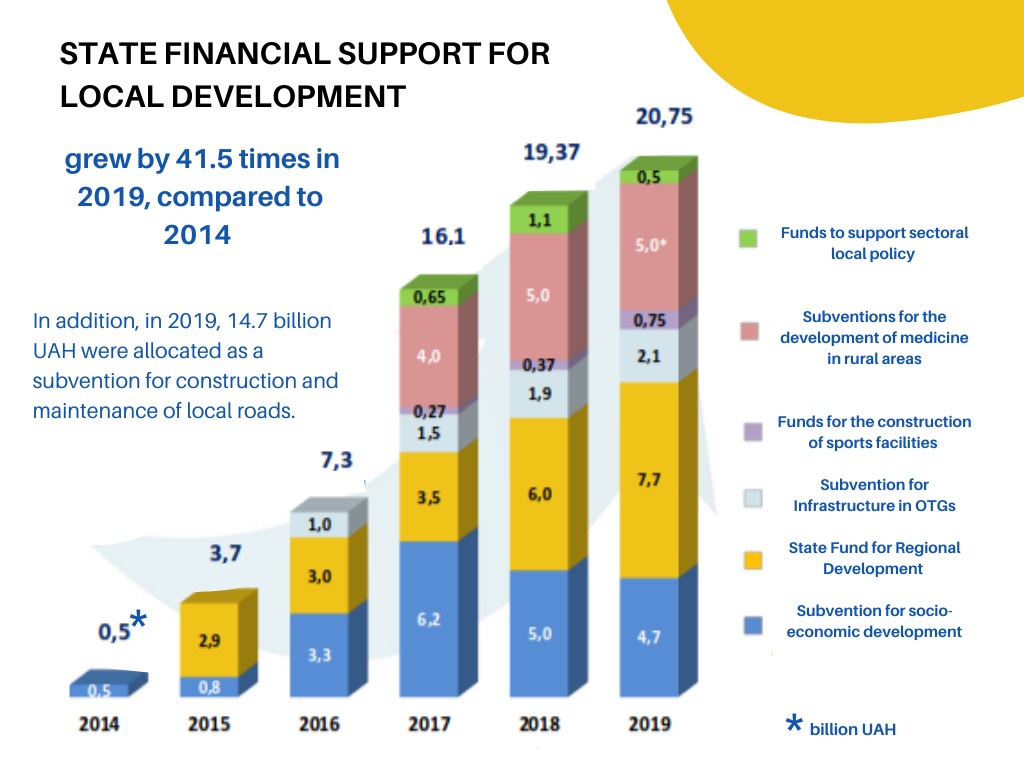

In general, state support for local development projects grew from 0.5 billion UAH (US $66 million) in 2014 to 20.8 billion UAH (US $770 million) in 2019.

The largest part of the State Fund was spent on regional development that finances various types of local projects on a competitive basis, as well as for two state programs: for the development of local sports facilities and local medical facilities for general practitioners.

Many examples of the implementation of state programs are impressive, especially taking into account how quickly they were implemented and completed.

In general, 640 of such new medical centers with facilities for general practitioners were built in Ukrainian villages in 2018-2020 thanks to the state program. Before, such centers were more than 50 years old and were located in old huts. 71% of them had no water and 75% no sewerage systems, according to a government report

.

In general, about 400 such sports facilities were built in Ukrainian municipalities in 2017-2019 with about 60% of costs allocated from the special state program. Such sporting grounds that are just a norm for any municipality in developed countries were rare in Ukraine until recently. People used to play games on the village pastures or old Soviet sporting ground near schools.

Overall, 280 schools were reconstructed in Ukraine in 2019 with the support from the State Fund of Regional Development. The Fund also funds other regional development projects.

In 2019, UAH 14.7 billion (US$ 0.6 billion) was allocated in subsidies for the construction of local roads. Adding this state funding to budgets already implemented by local authorities, some municipalities managed to reconstruct or develop 70% of their local roads just in the last 3 years.

Baranivska OTG in Zhytomyr Oblast became one of the symbols of Ukrainian decentralization. It not only implemented all the mentioned infrastructural projects that became available with decentralization. It went the extra mile by turning its municipality into a brand and boosting local development.

The first step of the new OTG was to create the new emblem of the municipality in 2017. It included forests that cover ⅓ of its territory and also traditional flax, rye, and sheep. The emblem became prophetic. Soon after, Baranivka became famous in Ukraine as the biggest producer of organic milk that is also exported abroad.

Recently the OTG reached an agreement with a British investor to start cultivating flax once again so as to eventually launch a textile production, restoring the ancient tradition of creating flax-linen clothes.

Baranivka also develops touristic routes through its forests inhabited with unique species of deer. Finally, the “Youth cluster of organic business of Baranivka" has built a cheese factory in the village of Rohachiv.

Baranivka’s success stories were filmed by local school television. And we’re not even looking at the many ordinary enterprises of Baranivka that were created after decentralization which use the logo of the OTG as a symbol of healthy and high-quality products recognized throughout Ukraine.

Altogether, the results of financial decentralization are the most apparent among all Ukrainian reforms, and few would doubt their general efficiency.

Controversies with villages "married" to cities against their will

The period of voluntary unification, when local communities can choose with whom to unite, ends in 2020. With the local elections in October 2020, the government can incorporate the remaining separate communities into OTGs by its own decision. This move bears both positive and negative consequences.

On the one hand, unincorporated villages spend too much money to maintain ineffective management that can’t provide services due to its limited capacity. These villages are de-facto managed directly by the regional state administration and their inhabitants are often passive in terms of public participation. This is why these communities have not yet united into an OTG.

On the other hand, the government’s plan for compulsory unification often unites small villages with huge cities and creates large OTGs with one public administration for dozens of villages, contrary to the will of the local inhabitants. The reasons behind this include lobbying from big cities and also state criteria that prefer creating larger catchment areas rather than considering the wishes of locals.

Ending the reform period with such impositions from the state, even if done with good intentions, runs contrary to the European charter of local self-government

that Ukraine has signed. In particular, article 5 that states:

“Changes in local authority boundaries shall not be made without prior consultation of the local communities concerned, possibly by means of a referendum where this is permitted by statute.”

This principle was generally abandoned regarding unincorporated municipalities by the majority of Ukrainian politicians. They claim unification is needed for the sake of efficiency. Such a claim makes some sense, as the above-mentioned examples of effective OTGs demonstrate. However, the argument of law and the right for free local governance is not one worth abandoning, Ihor Hurniak, Ukrainian lawyer and researcher of local governance, explains. In principle, any municipality can change its boundaries only voluntarily.

Furthermore, another controversial step in the reform was made in 2018, when the government allowed big cities with populations ranging from 50,000 to 1 million (of which there are 180 such cities in Ukraine) to unite with surrounding villages.

This was sometimes done on the basis of mutual agreement for the benefit of both the larger and smaller communities.

But often the surrounding villages were "married" to cities against their will, as the city was hungry for the village’s valuable land. Often, local corruption enabled this transaction.

In 2020, according to the government-approved plan of the new Ukrainian municipalities, many villages were forcibly attached to cities with populations hundreds of times greater, sparking protests throughout Ukraine. Although agreeing to concessions in some instances, the government hasn’t refrained from compulsory unification as a policy in general.

For example, in the Lviv Oblast, the central government proposed to create a Lviv OTG that would unite the city of Lviv (population of 800,000) with dozens of surrounding villages and towns (average population of 7,000 each). Most villages rejected this proposal by public hearings, making any further amalgamation unconstitutional. Nonetheless, after constant protests, only 11 villages defended their independence in three separate OTGs while all the rest will be managed by the council of Lviv from October 2020..

Last but not least, decentralization in Ukraine is creating municipalities that are too large for a fair and equal distribution of funding and resources. Half of the Ukrainian territory is not yet incorporated into OTGs, but the government proposes to create only about 500 OTGs for these territories, huddling the remaining villages into oversized municipalities. This bears the risk of not all villages having proper access to local services, as was initially intended.

Nonetheless, the balance of positive and negative consequences in decentralization reform is clearly more than favorable for rapid local development.

Read also:

- Experts question future of Ukrainian judiciary as court cancels judicial reform

- Moratorium on land sales no more: how Ukraine’s land market will operate with the new law

- Ukraine launches large-scale reform for its post-Soviet prosecutor’s offices system

- Russian as a minority language in Ukraine vs Russian as Putin’s weapon: Is there a compromise?

- Ukraine’s ambitious health reform now hangs by a thread

- Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

- The rebirth of Ukrainian literature and publishing: famous contemporary authors and new policy for their support

- Despite second attempt at judicial reform, political decisions rule Ukrainian courts

- Corrupt and biased judges still pollute Ukraine’s judiciary; Zelenskyy’s reform will not fix this

- Reforms in Ukraine are increasingly stagnant, experts say

- 10 successes of Ukraine in 2019 you don’t know about but should