Moscow’s falsification of the history of the Circassians and its disavowal of the imperial nature of Russian policy that led to the expulsion of most of the members of that nation not only shows that the Russian government is committed to a neo-colonial agenda but is continuing its course of ethnocide, Madina Khakuasheva says

.

The senior researcher at the Kabardino-Balkar Institute for Research on the Humanities argues that it is thus a major mistake to dismiss Russian propaganda as so absurdly at odds with the facts that it does not require an answer.

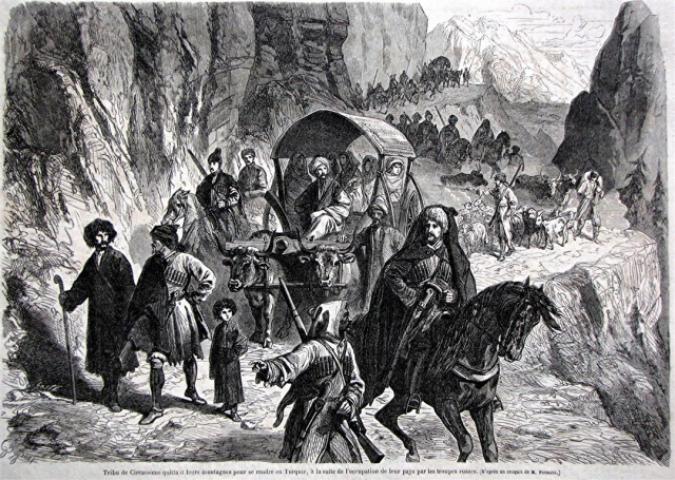

Instead, the amoral and immoral lies about the past Moscow is now promoting are at the center of “a well-thought out but gradual realization of ethnocide” of the Circassians and other non-Russians the Russian state has conquered over the course of its history and thus are an indication of where Moscow is now heading.

Russia’s approach to the non-Russians has gone through the following stages in the case of the Circassians, Khakuasheva says.

In addition, she continues, Moscow continues to work to create “all the conditions for the realization of artificial assimilation and the erasing of all evidence of the existence of an entire people,” including declaring the territory and resources of those territories Russian “’from time immemorial.’” “That is the final goal of geopolitical control.”

Russian writers in this area make a number of claims which on even the most superficial examination collapse, the scholar says. For example, some of them claim that “The Russian-Caucasus war began because of attacks by the mountaineers on Cossack settlements,” without addressing the question as to why the Cossack settlements were there.

They assert that “the Circassians just like all backward colonized peoples are divided between ‘good’ ones [who are the majority and welcome being conquered] and [the few] ‘bad’ who resist this but don’t explain why 95 percent of the Circassians had to be expelled from Russia at the end of the war.

These Russian writers argue that as far as “the Circassian apocalypse” is concerned, “the Circassians themselves, their special clan, inter-tribal and ‘feudal’ disagreements are to blame.” And they continue to refer to the 1864 expulsion not as the genocide it was but as “so-called” or at least invariably placed in quotation marks.

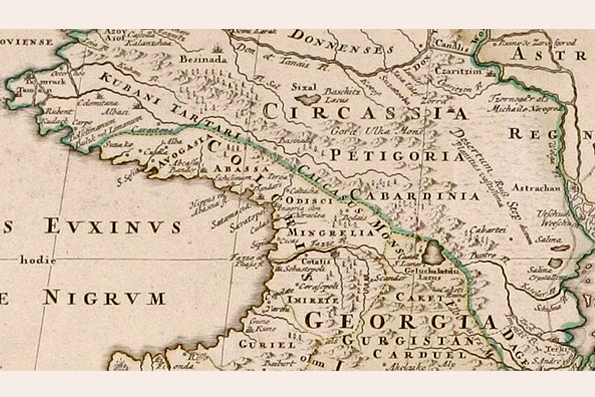

Underlying all these falsehoods, Khakuasheva says, are “exclusively geopolitical interests,” including first and foremost “geopolitical control” of the territories that belonged to the Circassians.

This isn’t something new: it has its roots in Soviet times; and it has continued because even after 1991, the Russian state was unwilling to recognize the imperial and colonialist nature of its Soviet and tsarist predecessors. And because these were not judged then, they are now being celebrated.

When Russian writers aren’t issuing falsehoods about the Circassians, they are working to erase them from historical memory, eliminating references to the Circassian nation in history textbooks, demonizing all those who remember or seek to discover the truth, and trying to distract others by emotional tales or denouncing them as Russophobes.

The combination of these measures, Khakuasheva says, are intended to prove to Russians and everyone else that the Russian state has always followed “’a uniquely correct course.’” And attacking Circassians in this way was convenient because so few were left in the homeland and the millions abroad were spread across the world.

But now thanks to the Internet and social media, the diaspora has come together and is in a position not only to respond but to encourage Circassians in the homeland not to believe the lies that the Russian state today is using for exactly the same purpose the tsarist forces used guns and boats to drive them from their homeland.

As a result, Circassians abroad and Circassians in the homeland understand what the facts of their history are and how wrong Russian propagandistic interpretations are.

Khakuasheva gives two examples of this Russian reaction: the insistence that Krasnodar and Stavropol krays were Russian “from time immemorial,” when even earlier standard Russian histories show they weren’t, and the erection of statues of tsarist generals in places where they conquered and killed during the Russo-Caucasian War.

“To erect monuments to the murderers of the Circassian people on its historical motherland,” the historian concludes, “is approximately the same as it would be to put up memorials to generals of the Third Reich in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.” That would not be tolerated by anyone and neither should the Russian actions and claims be.

Read More:

- Marking Day of the Circassian Flag online – a national action the pandemic couldn’t stop

- The Unsung Lament: Russian Atrocities in Caucasus

- Russia’s act of genocide against Circassians lasted more than 150 years, Chukhua says

- Russians won’t admit expulsion of Circassians was genocide — but Ukrainians should

- North Caucasus republics could flourish on their own, Israeli political analyst says

- Russian outpourings into the Caucasus

- Stalin starved populations to death to russify Ukraine, North Caucasus and Kazakhstan, statistics show

- Stalin’s Caucasus crimes Putin wants you to forget