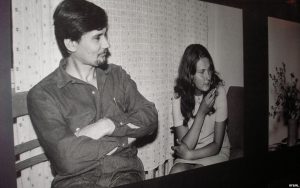

The Vertep in itself was an act of fearless defiance in the USSR, where both religion and Ukrainian national traditions were essentially outlawed. Nineteen people, among which were the best of Ukraine's dissidents, were arrested in Lviv and Kyiv. Among them - Vasyl Stus, Ivan Svitlychny, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Iryna Kalynets, Stefaniya Shabatura, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Leonid Pliushch, and others. Radio Liberty presents some unique photographs from the personal archives of the 1972 Vertep members.

The 1972 Vertep in Lviv was an open protest against the communist government, which was destroying Ukrainian traditions, had banned all religious holidays, and imposed atheism. The participants planned to use the funds collected from caroling to help political prisoners and the publication of the Ukrainian Visnyk (Herald), managed by opposition figure Vyacheslav Chornovil.

That year, the KGB had started a special operation against the Ukrainian samizdat ("samvydav"

in Ukrainian), the clandestine publication of literature banned by Soviet censors, in order to neutralize the Ukrainian intellectual elite. Samizdat in Ukraine was popularized and carried out by the Shistdesiatnyky (Sixtiers) movement, a literary generation that began publishing in the second half of the 1950s and played an important role in strengthening the opposition movement against Russian state chauvinism and Russification. The members were completely silenced by mass arrests from 1965–72.

Vasyl Stus, a prominent Ukrainian poet who was killed in the Soviet Gulag, had spent the New Year and Christmas in Lviv that year. He joined the participants of the Vertep organized by Olena Antoniv, doctor, activist and wife of Vyacheslav Chornovil.

The Vertep performance is an enactment of the Nativity with merry interludes depicting secular life. There can be 10 to 40 Vertep characters, typically among them a sacristan, angels, shepherds, Herod, three kings, Satan, Death, Russian soldiers, gypsies, a Pole, a Jew, a peasant couple, and various animals. Vertep performances date back to the late 16th century. They reached their height in popularity in the second half of the 18th

century, but started declining in the late 19th century, and were completely banned during Soviet times. In 1972, the Vertep performance served as a rallying point and symbol of resistance for Ukrainian dissidents who went from house to house of the Lviv intellectuals on the night of the "Old New Year," celebrated in Ukraine as a relict of the Julian calendar.

Poet Ihor Kalynets, who was arrested several months after his wife Iryna and survived labor camps and exile, remembers that all the homes were thoroughly searched and books and written materials were confiscated.

“The 1960s were exhilarating years as more and more samizdat literature was published and read by society; all sorts of manuscripts went through our hands…. Symonenko’s poems, Kostenko’s verses, great literary works!

The first arrests in Lviv took place in 1965. That’s when our ideologue, Vyacheslav Chornovil, appeared. This was the first wave of arrests. The trials started in 1966, many people attended, and the police were unable to control the crowds. Firefighters dispersed people with water. This was the first political rally in the Soviet city of Lviv. There were arrests and murders. Chornovil created the Committee for the Protection of Political Prisoners in the early 1970s and began publishing our samizdat magazine Visnyk. The KGB knew they couldn’t intimidate everyone.

Then came 12 January 1972, when all the members of the intelligentsia involved in samizdat literature were massively arrested. I protested against these trials and my wife’s arrest. It was the largest wave of repression in the Soviet Union. Individual arrests continued until the end of the 1980s,” recalled Ihor Kalynets.

The Soviet authorities understood that the dissidents' nominal observance of religious holidays was too minor a reason to initiate mass repressions of the movement. This is why they found a more weighty justification - a link allowing them to prove the "connection of the nationalist underground in Ukraine with the foreign Ukrainian centers and organizations," writes the Ukrainian historical publication Istorychna Pravda

.

The scenario of the so-called "Dobosh case" was planned by the state security organs. The chief role was played by Yaroslav Dobosh, a Belgian student of foreign origin, who tried to gather samizdat copies in Kyiv and Lviv and take them out of the Soviet Union for the Ukrainian Aid Committee and the Ukrainian Youth Union of which he was a member.

4 January 1972 was the start of the Soviet operation against dissidents. Dobosh was detained at the border of the USSR and had a copy of the "Dictionary of rhymes of the Ukrainian language" by political prisoner Sviatoslav Karavanskyi confiscated. The student was accused "in carrying out subversive anti-Soviet activity."

A notification about his arrest appeared only after 11 days, in the newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, "Soviet Ukraine." Apparently, the time was used to intimidate the victim and document the confessions. Mass repressions against leading opposition figures followed on 12 January - their flats were searched, with Russian and Ukrainian samizdat copies confiscated. Dissident leaders, including Ivan Svitlychnyi, Vasyl Stus, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Zinoviya Franko, Leonid Plushch and others, were imprisoned. At least 19 persons were arrested between 12-14 January 1972.

During interrogations of Iryna Kalinets and Stefania Shabatura at the Lviv detention center, KGB officers tried to obtain information about their contacts with other participants of the dissident movement (in particular, with Stus), exchange of the samizdat brochures, the full list of participants of the vertep, their contacts with foreigners, etc.

The arrested dissidents were threatened with executions, physical torture, harm to relatives and loved ones.

The system of "punitive psychiatry" was also used: some who were difficult to accuse of violating the relevant articles of the Criminal Code were declared insane and imprisoned in special hospitals.

Most were sentenced to five to seven years in strict regime prison colonies and three years of exile. The main purpose of the January repression of 1972 was to neutralize the most active leaders and intellectual elite of the dissidents and intimidate the rest.

While twenty prominent figures of the movement were arrested in January, 89 dissidents (including 55 from Western Ukraine) were convicted in 1972. Then, the well-known dissident researcher Liudmila Alekseieva wrote: "The arrests seemed to be part of a well-conceived plan to eradicate the self-consciousness of Ukrainians."

According to Mariya Hrytsiv, the January pogrom of 1972 and the persecution of participants in the nativity scene interrupted the tradition of a public celebration of Christmas for a long time and suspended the mass publication of samizdat.

However, as early as the second half of the 1970s, the resistance movement resumed with renewed vigor, and open protection of human rights by the members of the Ukrainian Civic Support Group of the Helsinki Accords, also known as the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, became the main instrument for combating the system.

Read also:

- From Stus to Sentsov: Ukraine’s Soviet-era political prisoners of the Kremlin

- How Ukraine’s Vasyl Stus used poems to fight the Soviet Regime

- Ex KGB agent who repressed Ukrainian intellectuals among country’s most influential persons. How come?

- ‘What can Ukraine expect from the West now?’ – former GULAG inmate asks bitterly

- Ukrainian human rights group that helped bring down Soviet Union turns 40