On 21 February the Free Academy of Change in Kyiv hosted a discussion called “Ukraine and Reform: A Success or a Farce?”

Oleksander Paskhaver, an economist and advisor to three Presidents of Ukraine, Yaroslav Hrytsak, a well-known historian and author, and Volodymyr Dubrovskyi, the Senior Economist and chief expert on taxes and budget reform from the Reanimation Package of Reforms reforms coalition together spoke about this subject. Here we offer the reader a chance to become familiar with these speakers’ theses.

Oleksandr Paskhaver: When speaking of reform we keep to a specific definition. If one speaks about the relation to our ambitions, then nothing has been done. If we speak of things in relation to that which had been accomplished before the Maidan, then what has been done has been totally unexpected when taking into account the objective characteristics of our country and the majority of the population.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: This question is impossible to answer because it is not formed correctly. I would rephrase the question this way: have reforms come far enough over the last four years that they cannot be undone? And if they haven't come far enough, what must still be done to make them irreversible?

Dubrovskyi: Many people wanted our reform process to be a sprint, but really we find ourselves in a marathon.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: This all depends on the criteria. Many people wanted our reform process to be a sprint, but really we find ourselves in a marathon. Much must be changed, and some things cannot be changed quickly. These are such fundamental things as values and customs, the inclinations and beliefs of the people which are changing much faster than they had previously changed, but still need years to finish changing. In this marathon, there were particular “spurt runners” who sped up until they passed everyone else and then went back to jogging. We need to understand that we are running a marathon, and we need to build a strategy accordingly. Without a doubt, we have had success, but this success will not quickly show its marks.

Paskhaver: A strategy of survival dominated Ukraine for a century, and this ethic counteracts today’s European values.

Oleksander Paskhaver: Our western advisors frequently complain that we are unable to do what Poland and Estonia did and therefore we are failures. This is a total misunderstanding of the differences between Ukrainians and Poles or Estonians. Poles and Estonians already possessed European values, so that it was easy for them to set up institutions which were based on European values. We are very far from these values. Significantly, a strategy of survival dominated Ukraine for a century, and this ethic counteracts today’s European values. Therefore we need to take a long road of the slow change of social values if we are to be persistent on the path to European civilization. Neither Poles nor Estonians nor Czechs did what we have to do. Therefore, I say that we are still not yet a European country, we still have to become a European country.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Historians say that successful transformations take, on average, fifty years. We are still in the middle of that path; therefore, it is too early to judge. Ukraine as a country is a “distance runner.” It is not possible for Ukraine to run at a sprinter’s pace. But even in a distance run spurts – moments of acceleration – are important. History shows that nearly every country which reformed successfully had such spurt moments, and in each case, we can identify them. If we are to sprint for a spurt, then we will cover the distance quicker and with less sacrifice. If there are no spurts, then it is unknown whether we can cover this fifty-year distance successfully.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: Many people, especially economists, argue which is better: slow reforms (gradualism) or quick reforms – so-called “shock therapy.” Really this argument is pointless. The pace of reforms is determined from within, not externally. The argument only makes sense if you believe that Ukraine has an all-powerful and benevolent government which only considers what is best for the country and is free and able to undertake reforms at the speed which it determines. We do not have such a government, and developing countries, by definition, cannot have such a government.

Oleksandr Paskhaver: Ukrainian history has fostered a strategy of survival which contradicts the values of active development. That's why we cannot move quickly. We need a strong push to change our values. We can want everything to be fast, but this is a mistake, and it is a mistake when we are advised to work quickly. People who advise this do not understand our people and our values.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: This is an important nuance. These reforms affect wide layers of the population, millions of people. And these reforms must be undertaken slowly because these people need to adapt to them. We do not have other people. If advisors advise otherwise, let them go to countries with other kinds of people.

However, there are many reforms, which affect the rules of the game, rules by which the elite are formed and by which the elite play. Changes to these rules can be made faster if they are possible. The people who oppose reforms have time, when reforms are slow, to create a wide opposition and drown the reforms while they are still beginning or in the middle. But if reforms are enacted quickly, these people find themselves in conditions of new rules which they did not want; but if they are unable to play by these new rules, then the new rules lead to their replacement, as occurred in our times with the example of the “Red Directors.” And this does not lead to any sort of social tragedy, it is normal upward mobility.

Dubrovskyi: You cannot change the whole nation quickly, but you can change the elite if you change the rules of the game.

Truly one must understand two things about the speed of reforms. First: you cannot change the whole nation quickly, but you can change the elite if you change the rules of the game. And if these rules are changed and the elite change, then totally new people rise to the top of the nation, to the sphere of decision making, and the country itself begins to change. The leadership becomes an example to all others, for a large number of people follow those who are at the top. Second: successful reforms absolutely require a change of values. Values truly change across generations, but in many cases, it is enough to simply change wrong beliefs or bad customs. If people, who today are convinced that it is OK to vote for any thief as long as he “shares the spoils”, instead begin to vote according to other criteria – this will be a success. And for this it is not necessary to change the values, people simply must believe in something which will influence the making of decisions. And then they can change the country quickly enough, even if they are not ready for it.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Here is one important conclusion – history has significance. When Douglas North asked to be an advisor to a country that requires reforms, he would take a sabbatical for several months and read books on the history of this country, so that he could understand whether or not reforms would be successful, or at least which would be successful. History is a great gravitational force, and to overcome it one must develop appropriate tactics. We cannot simply ignore history.

History determines various things – religious beliefs, which provide an ethical framework; the factor of violence which forces people to fear and barely survive; the inculcation of political traditions. Ukraine suffered a traumatic 20th Century. Consider: we lost almost an entire generation which otherwise could have given the youth their heritage. Leaders of each generation either shut their mouths or lost their heads. In short, people learned not to live full lives, but to survive. Therefore our society is dominated by the values of survival – together with corruption, which is nothing other than a simple means for solving complex problems.

The appearance of this generation is really a huge chance for Ukraine, but it remains a chance, not a reality. For it to become a reality, this generation must reform its political structure and pressure its leaders. I consider this the most important work to be done. The “spurt” can only occur when a new political class is formed.

Paskhaver: The complaint “Three years have gone by, and reforms still are not finished” is a silly one.

Oleksandr Paskhaver: We do not have people who change quickly. The process of change relates to the change of the elite. In countries which began to build capitalism, there was a revolutionary bourgeois class which could organize resolutely and at the same time held liberal political convictions. And even this class required decades changed its countries. Therefore the complaint “Three years have gone by, and reforms still are not finished” is a silly one.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: People who undertake reforms are not necessarily the people who sit in the government. In 2010 a study by Francis Fukuyama and Brain Levy showed four sequences of development.

This gives a fascinating answer to the question of why Ukraine is not Singapore. Singapore had nothing to start with but a strong state government founded on a tradition of Confucianism. This created a situation were one well-educated man came and, taking control of the bureaucratic apparatus, was able to change the country. This success was repeated nowhere else, and clearly, it will not be. Fukuyama and Levy include Ukraine as an example in which, in the absence of all else, the engine of development will be the civil society. Ukrainian civil society really is an engine for promoting reform. Sometimes it even succeeds in promoting decisive reform quickly.

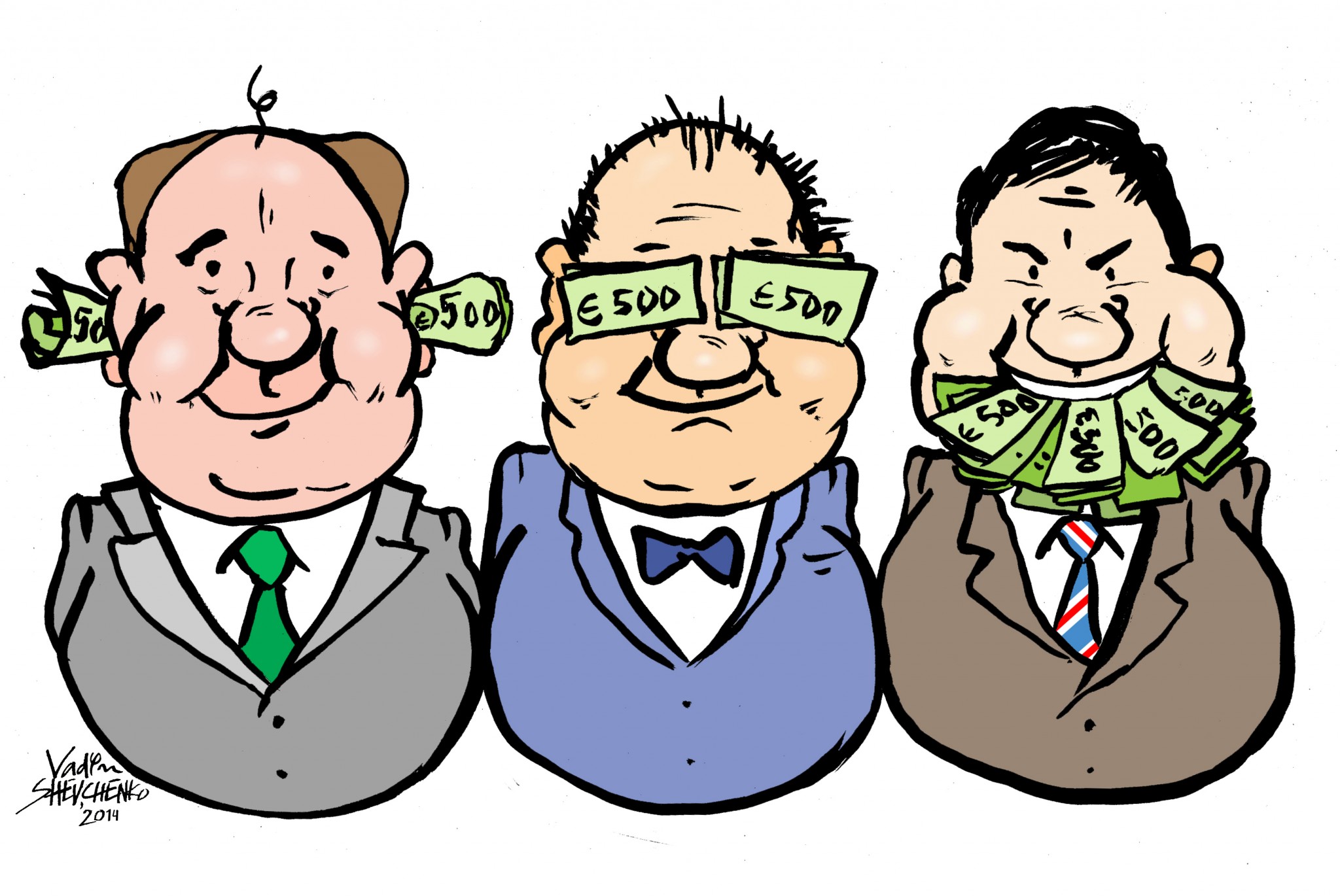

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Historians must be empirical, that is they must rely on facts, and not on theories, even when the theories are attractive. A study appeared somewhere about six months ago which compared the experience of all the former communist countries in the last 25 years. On the basis of continual statistics the authors arrived at this conclusion: when reforms are undertaken quickly – and this sounds strange – the social cost of these reforms is quite low. The first shock soon passes and the situation normalizes quickly. Contrarily, when reforms go slowly, then the cost which society must pay rises. Particularly, the slower the reform, the greater the chance for the appearance of oligarchs. Then the country passes under the so-called “Iron Law of Oligarchy,” which it is easy to fall under, and hard to get out from. So long as our state for different reasons chooses tactics of slow reform or no reform, then the cost will remain high and we will have an oligarchic order.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: I am critical of this study because you cannot consider the pace of reform to be an independent variable that someone can set. In Poland, reforms went fast because mature European values and a nearly-mature European civil society already existed there, and there was no question of “Where will we go? East or West?” Naturally, reforms occurred quicker there – and because they quickly changed the rules of the game, oligarchs did not appear. I agree that the oligarchic class is a result of slow reforms. But there are objective reasons for why the oligarchy came into existence. We generally had governments that did not want to enact reforms. Reforms occurred only during times of fiscal crises when the state ran out of money and it fell onto the fringe of survival. I’m pleased that the state bounced back from poverty two years ago already, but reforms have continued. Such a thing never occurred previously in the history of Ukraine. And this is only because we have a civil society which undertakes reforms and pressures the authorities to pass reforms.

Hrytsak: To criticize the current authorities is sweet and easy. But I consider that we must first criticize our own civil society. It is not yet able to place its own people into positions of authority.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Civil society, no matter how good and active it is, is not by itself able to change the country. All the main levers of change belong to the state. It is a simple law: the further East, the greater the role of the state. Therefore it is not enough to organize society to pressure the authorities. It is necessary for civil activists to become the authorities so that they can control the levers of change.

To criticize the current authorities is sweet and easy. But I consider that we must first criticize our own civil society. This criticism is and must be benevolent, but it is no less a criticism. We more-or-less understand our own authorities. But what to do with the phantom which is called “civil society” is not clear. It is not yet able to place its own people into positions of authority.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: No. The words here are not about the generation, but about those persons who lay claim to the role of its leaders. A generation is not a biological association, it is, conditionally speaking, people who grew up between certain years. To use a metaphor: all the people who grew up during a specific time, they are simple dough, prepared for something. They only receive flavor when somebody adds salt. It follows that whoever adds salt to this generation will give them a voice and form their positions. My criticism is of those politicians who try to set themselves up in this generation’s name. If somebody wants to “add salt,” then he needs to be able to prove by his personal behavior that he has certain personal values which he does not compromise. As a private individual, you may allow yourself fancy apartments or an expensive wedding, but this must be done privately. If you are a public figure or a political leader, especially in a poor country, then you do not have the right to these things. This should dictate your personal morality, and if you don’t have any morals, then at least understanding or wisdom or even cynical cunning should dictate these things. People look to you, you serve as a model which is afterward copied. Almost no political elites right now serve as models. They must live as they preach. But right now we don’t have anyone like this. And when there is such a vacuum, everything seems built on cynicism, and this is bad.

Oleksandr Paskhaver: I think that all this is linked to the fact that we followed Europe in its Post-Modern ethic. This is an ethic which is flexible, it is oriented on the desires of the individual and self-development. The time of prominent accomplishments in Europe and the creation of capitalism had as its foundation a rigid Protestant ethic. The Post-Modern ethic is reminiscent of that which occurred during the epoch of the Renaissance when everything was centered on the needs of the individual, and this resulted in an explosion of culture, but it reduced social mobility. In response to this came the Protestant ethic. We were unlucky in the sense that we are building our country during a period of flexible ethics. I am absolutely sure that the Post-Modern ethic is not a new ethic, but rather a crisis of ethics. Necessarily at some point in the near future, a new, rigid ethic will win out. Martin Luther’s Protestantism spread across half of Europe in only 40 years, once it became needed.Paskhaver: We were unlucky in the sense that we are building our country during a period of flexible ethics. I am absolutely sure that the Post-Modern ethic is not a new ethic, but rather a crisis of ethics.

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Three historians I am acquainted with told nearly at the same time,

“Post-Modernism is dead, and it died on the Maidan.”

Furthermore, not one of them is a Ukrainian. Why is this important? Because certain things can be seen clearly only from a distance. In 2014, the world was watching the Maidan because this was a great hope for the birth of something new. Unfortunately, it faded. I do not say that it faded completely, but the charismatic driver which existed in 2014 is no more, and it becomes ever weaker and weaker. We [Ukrainians] now wait for something really horrible to happen. All because we live in a world with many irritants, especially on social media, which make people very anxious and cause them to lose certainty because the purposes are lost. Is this good? Yes, because it strengthens metaphysical terror, and that is a strong driver. Martin Luther did not think about how to save Germany. He thought about how to save his own soul and the souls of other Catholics. This was a metaphysical terror. Therefore I support this thesis: we should not expect a new “-ism” which is built on certain interests, but we can expect a quasi-religion, something which will appeal to more than our interests.Hrytsak: In 2014, the world was watching the Maidan because this was a great hope for the birth of something new. Unfortunately, it faded.

Volodymyr Dubrovskyi: Many of our people primitively measure reform in the introduction of banal European norms. We say, let us look at the experience of developed European countries and do as they do. But adopting external shells which appeared there is absolutely absurd. We need to adopt principles, and the main principle is to lay a path that has already been walked. In Europe, there are laws which constrain people, but they are few. The greater proportion of the laws arose from social practices which were enshrined in law.

Article prepared by Myroslava Martyniv. Published by Zbruc.eu

Read more:

- Speed of Ukraine’s reforms slowed down since 2014, unclear outlook for 2018: Analysis

- Education reforms lead to newer, better, regional schools

- The struggle for Ukraine: a detailed analysis of reform and failure after Euromaidan

- Ukraine’s reforms on the rule of law have stagnated

- Decentralization reform can be Ukraine’s success, if it doesn’t stop halfway

- Swedish ambassador: Ukraine’s reforms easier to see from outside

- Reform to deoligarchize Ukrainian politics reaps first results

- Electing bad leaders in Ukraine: how to break the vicious cycle #UAreforms

- Ukraine makes progress in media freedom, but oligarchs still run the show

- Will Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Court be another imitation of reforms?