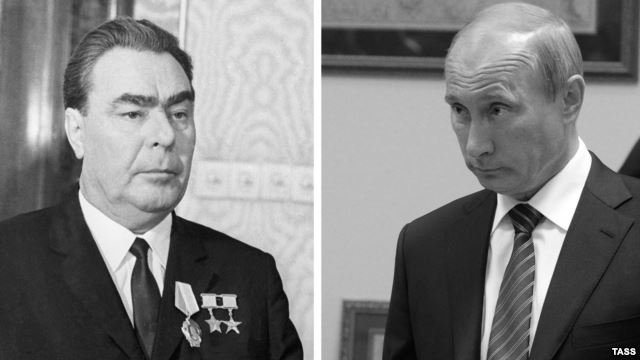

On the first anniversary of Vladimir Putin’s decision to introduce Russian forces into the Syrian civil war on the side of Damascus dictator Bashar al-Assad, commentators in Russia and Ukraine are pointing to ways in which this conflict recalls Moscow’s earlier interventions in Chechnya and before that in Afghanistan.

Their conclusions should be disturbing to all people of good will around the world given the brutality of Soviet and Russian actions in those wars, but they should also serve as a warning to Russia and Russians given that such military adventures did not end well for their authors or their authors’ country, however many victories Kremlin propagandists may claim.

Independent Russian military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer notes that in Aleppo,

Whether this constitutes “’a war crime,’” the analyst says, is up to an international tribunal; but of course, if it is found to be such in one case, it could easily be extended to others.

Russian military commanders believe that if they can take Aleppo, “this will be a decisive victory” in the Syrian civil war, one that will give Asad a victory and make Damascus into what was true in Chechnya after the second Chechen war, a pro-Russian vassal that will help project Moscow’s power in the region.

But, Felgenhauer argues, Moscow is wrong.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian journalist Vladyslav Kudryk compares what Putin is doing in Syria with what his Soviet predecessors did in Afghanistan, a conflict that undermined the USSR, led to a Soviet withdrawal, but didn’t solve the problem of that Central Asian country.

At the moment, he says,

Moscow’s main goal in going into Syria was to force the West and above all the US to make a trade, with the West paying for Russian cooperation against terrorism in the Middle East with an agreement to end sanctions against the Russian Federation for what Putin is doing in Ukraine. But if that was Moscow’s goal, it has clearly failed.

What is worse for Moscow, experts like Ihor Semyvolos, the director of Kyiv’s Center for Near East Research, say, is that Moscow has little choice but to keep fighting despite the increasing costs it is imposing on itself by that policy. “In authoritarian regimes,” Semivolos note, “defeat in war usually very quickly leads to the fall of the regime.”

Moscow is thus caught in a trap of its own making, incapable of winning either on the ground or in diplomacy but equally unwilling to take the risks involved of pulling out entirely. Russian leaders know what happened after Gorbachev pulled out of Afghanistan, and they don’t want the same outcome.

Related:

- How Russia tried to cover up death of Putin's best helicopter ace in Syria

- Putin's hybrid war objective is to capture effective control, Sazonov says

- The Ordinary Fascism

- Putin happy to see refugee crisis unsolved

- Young Russians flow en masse to fight for Islamists in Syria and Iraq

- Ukrainians and Syrians are victims of Putin's paranoia