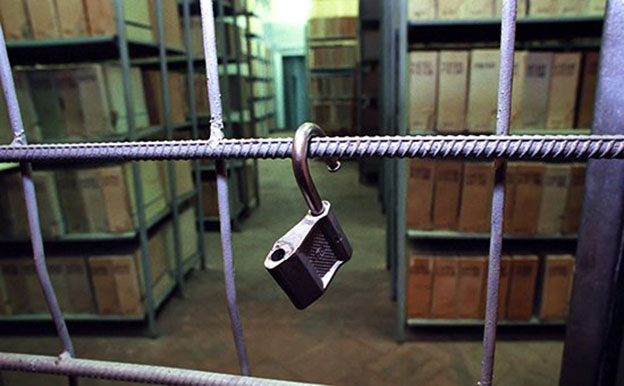

One of the results of the Maidan is the transfer of the KGB archives to the National Memory Institute and access to the files for the Ukrainian public. A major step, considering the fact that Ukraine was the second largest Soviet republic, and that the archive of the largest Soviet republic – Russia – remains closed and will almost certainly remain closed for many years or decades to come.

The KGB archives will provide us with a much better understanding of how the Soviet state kept its people under strict control, and how repression was operationalized. It will also tell us more about the functioning of Russia’s FSB, as that organization operates to a large degree along the same lines, and with the same vision perfected by the KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov in the years 1967-1982. Still, the opening of the archives also has another side.

Read also: Ukraine prepares to make Soviet KGB archives available online

The other day my good friend Semyon Gluzman told me that some Ukrainian journalists had come to interview him. To his surprise they explained to him while preparing for the interview they had studied his KGB file, and had found many interesting details about his criminal case. Gluzman, who served ten years of camp and exile for opposing the political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, was rather bewildered: how could this be? It turned out that he had not specifically stated that his file should be made available only with his personal permission, and thus anybody now had access to the intimate details of the case the KGB concocted against him 45 years ago. The journalists saw what Gluzman himself never wanted to see. There is a short documentary made in the late 1990s by the Dutch cinematographer Alyona van der Horst, featuring Gluzman and the then deputy chairman of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), Volodymir Pristaiko. Pristaiko wanted to do Gluzman a favor, and in the film hands him his personal “case”, nicely packed in a box on the table. Gluzman refuses: he does not want to know who spied on him or gave information that was used to put him behind bars. He pushed the box back, and never took it home.

The case of Gluzman is just one example of how complex the issue of KGB archives actually is. Several years ago I did research for my book Cold War in Psychiatry in the archives of the Stasi in Berlin. Part of the research consisted of going through many meters of personal archives of people who had been “informal agents” of the Stasi, people who had agreed to provide the Stasi with information on people in their environment, including friends and even family members. There were times when I had to abandon my desk at the archives and go outside, so nauseous had I become by reading what was made available to me. Many people had been coerced to work for the Stasi through blackmail, having either violated the law themselves or because the Stasi found out they had secret affairs, and once a person was “hooked” the downward spiral began, gradually destroying the moral core of the person and reducing him to a little wheel in the huge repressive machinery. Thus, I discovered the gynecologist that had infiltrated the organization for whom I worked, which fought the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR. When reading her file I was left with a combined feeling of pity and disgust. What started with her own discovered love affair (piles of love letters were lying in the archive) turned into a machinery in which the recruited “informal agent” wrote daily reports to the Stasi indicating which of her patients had a venereal disease and thus might be having a love affair on the side. Hundreds of people were denounced, probably subsequently themselves coerced into spying. In the end “my” agent fled to the West, and killed herself after German reunification in order to avoid disclosure.

In the 1990s a group of German psychoanalysts studied how and why people had agreed to work for the Stasi, and how they themselves perceived their collaboration. Some had agreed to become agents out of conviction, wanting to defend the socialist east German State, yet many others had been coerced either because of disclosed transgressions or because otherwise their careers or university studies would be obstructed. To many of them the task seemed a simple and rather innocent one, just a conversation in a café every now and then, and they even wondered why the information they provided was of any interest to the Stasi. A crucial element in many of the personal stories was the fact that it had not been the “informal agents” who wrote reports, but their “guiding agent” (Führungsoffizier), who conducted the conversation in a café and then submitted a report to the agency. The “informal agent” never saw these reports, and had no knowledge of the content (and sometimes not even of their existence), yet it was these very reports that were later used to judge whether an “informal agent” was deemed to a collaborator of the Communist regime and banned from his/her profession or any governmental job. It is important to note, however, that every Führungsoffizier had a plan to fulfill, like anybody else in the socialist plan economy, and thus stories were either beefed up or maybe even invented, because the quality of information gathered would affect the career of the Führungsoffizier himself. So who could judge after the collapse of the GDR regime whether the reports in the file were truthful or not?

In a civil society a cornerstone is the rule of law, and this is based on the presumption of innocence. People are guilty only when proven to be so without a trace of doubt. KGB files, like the Stasi files and the files the other secret agencies that spied on people, are full of broken lives, of people who tried to save their own skin by providing a little information, and sometimes a bit more; people who wound up in the downward spiral of fear and blackmail, of winding up on the sliding slope and gradually losing their own human dignity. Papers tell only part of the story and are one-dimensional witnesses to the tragedies that unfolded. For us, outsiders, it is so hard to judge, in particular because we know how deceitful these agencies were.

In the course of writing my book I befriended an “informal agent” of the Stasi, a professor of psychiatry who agreed to collaborate out of conviction and wrote detailed reports that are now in my possession. He refused, however, to spy on people, to tell who committed adultery, was alcoholic or a hidden homosexual. The Stasi didn’t trust him – why agree to spy and still uphold moral standards?! So he was under surveillance himself for two years, and shortly before the Berlin Wall came down they even discussed banning him from foreign travel – and thus from carrying out his Stasi work – because he had become too anti-Soviet and pro-American. My “Stasi friend” lost his job, and also his wife, and was banned from his profession because of his Stasi past, and spent the next eight years contemplating suicide. Paradoxically, he turned out to be one of the most moral and ethical characters in my book. And if he had been doing his work for the CIA, MI5 or Mossad he had been considered a hero, rather than a traitor.

I am not saying all spies and informers were OK, and their collaboration with repressive secret agencies should not be analyzed. But it should be done with the utmost care, considering all the circumstances involved. Yes, the KGB, Stasi and similar secret agencies destroyed many lives. But they also destroyed many lives of those who were made to work for them, and we should not destroy more lives by opening archives without proper consideration.

Related:

- Ukraine prepares to make Soviet KGB archives available online

- In opening access to Communist totalitarian archives, Ukraine draws on European experience

- Russian historian: New laws on archives and names show Ukraine 'increasingly diverging' from Russia

- Punitive psychiatry returning with a vengence in Putin's Russia

- Psychiatric hospitals - a yet untouched corner of post-Maidan Ukraine

- When will Soviet psychiatry finally disappear?

- Kremlin - a 'psychopathic power with dangerous illusions,' Vike-Freiberga says