The use of “v” versus the use of “na” as a preposition about being “in Ukraine” has become so politicized that many Russians view the use of the first as indicating that the speaker backs Ukraine against Moscow while others see the use of the second as showing that its user is virtually a Russian imperialist.

But as in all such things, the reality is more complicated and has a most interesting history, something pointed out by Irina Levontina, a specialist at the Institute of the Russian Language of the Russian Academy of Sciences, in an interview given to Gordonua.com.

Language evolves all the time, and only rarely do its speakers recognize the change. Thus, in Russian, “metro

” used to be masculine although its ending would appear to dictate another gender, and “v” as preposition of “in the Internet” displaced “na” or “on the Internet” for almost all Russians except emigres. But “no one makes anything dramatic out of that.”

However, Levontina points out, with regard to the preposition to be used to designate “in” Ukraine, the issue was “not simply raised to the level of principled heights but politics interfered as well.” Indeed, not only do most people think that the choice has a profound meaning, but they make jokes about it.

Her favorite, she continues, the following: “’Yanukovych is put on the international search list but up to now, it isn’t known where he is: “na” Ukraine or “v” Ukraine.’”

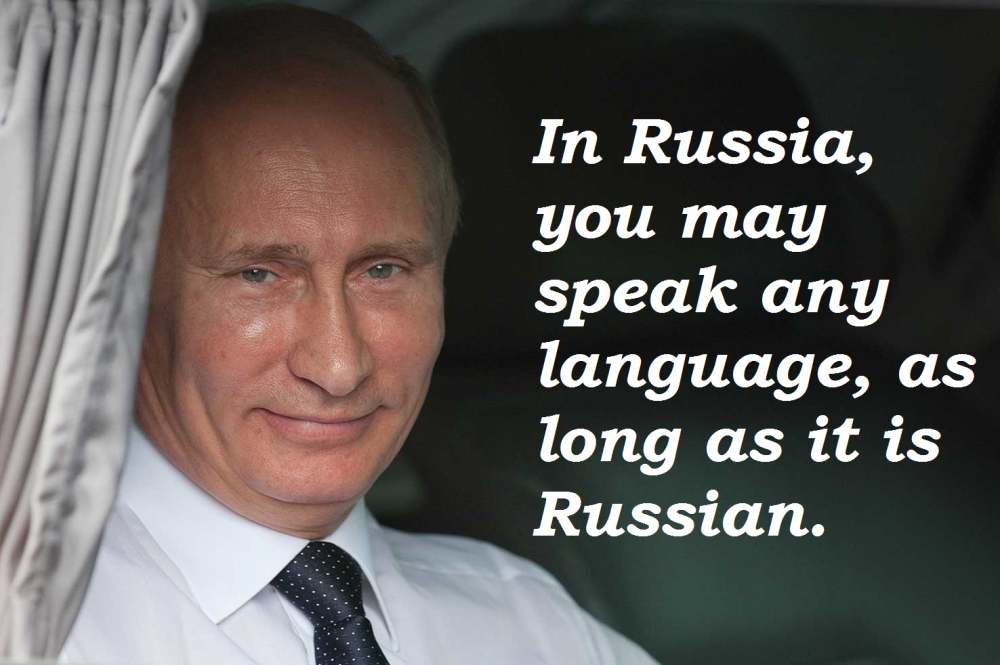

Before relations between Moscow and Kyiv soured, the Russian authorities asked linguists whether it would be all right to use “v

.” Then, “even Putin used the preposition ‘v.’” But his use of it depended on the outcome of talks on gas. “If everything went well, then it would be ‘v’ Ukraine; if badly, then ‘na.’” Because things went badly, the latter became de rigueur.

More than that, those linguists who questioned the latter were viewed as engaged in “the betrayal of [Russian] national interests,” and some even began to ask whether those who took that position had Ukrainian roots somewhere in their backgrounds.

Both of course are possible. According to Levontina, revered Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko [1814-1861] used both; but by the 20th century, “na” had become the norm in the Russian literary language. That reflects Muscovite usage, but elsewhere, including in Ukraine, there are regional variants and in Kyiv certainly “v” is thus correct. (She stresses she’s talking about Russian there and not the separate Ukrainian language.)

Levontina also discusses the evolution of meaning of three words from ones that designate an enemy to proud self-evaluations. These are “vata,” “ukrop,” and “colorad

.” The first has “a very interesting history in which are manifested the normal laws of the semantic development of the word.”

“Vatnik” and its derivative “vata” were first used as Ukrainian terms of abuse for those Russians who blindly follow “Russian imperial consciousness.” But very quickly, she says, those took it on as a term in which they were proud. This shift was special only in that it was so quick.

“A less complicated but similar history occurred with ukrop,” she points out. First, there was the abbreviation “ukr,” from which “ukrop” arose, first as a Russian term of abuse for Ukrainians and then as a Ukrainian expression of national pride. And “colorad” or beetle, as a term for Donbas residents who were pro-Moscow, evolved in the same way.

Levontina concludes by expressing the hope that current tensions between Russia and Ukraine and between Russians and Ukrainians will be overcome and that the two will have “normal relations. Politicians,” she says, “are insane; one can’t expect anything good from them.”