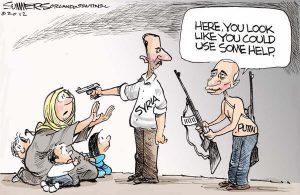

Ever more people are drawing parallels between Vladimir Putin and Joseph Stalin, but there is one parallel that has attracted less attention than it should, Irina Pavlova suggests, and that is this: Putin now is using his anti-terrorist campaign in the same way Stalin used his anti-fascist one, not to defeat an enemy but to expand Russia’s influence abroad.

In a blog post yesterday, the US-based Russian historian argues that “the goal of Russia’s military operation in Syria is gradually becoming ever more clear” and the parallels between what the Kremlin is doing now and what Stalin did in the 1930s and early 1940s ever more obvious.

“If Stalin in the 1930s had the goal of the sovietization of Europe under the flag of broadening ‘the front of socialism,’ then the present Russian leadership has as its goal the broadening of ‘the Russian world’ in the Middle East under the flag of the struggle with terrorism and the preservation of Orthodox civilization,” Pavlova says.

Sergey Stepashin, former Russian prime minister and now head of the Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society, has made that clear in two recent interviews, one with the Russian television channel “Dozhd” and a second with Israeli journalists.

In his “Dozhd” interview, Stepashin said that “for us, Syria is our culture and historical memory, more than Chersonesus [an ancient town in Crimea believed to be the site of the baptism of St. Volodymyr, the Grand Prince of Kyivan Rus - Ed.]. There a genocide against the Syrian people and Christian civilization is taking place. Russian Orthodoxy came from Syria.”

“These are not simply words,” Pavlova says. “The Russian powers that be for a long time have had an ambitious plan for expanding their influence in one of the most ancient cities of the Middle East – Jerusalem – a plan which they are now carrying out.”

“These are not simply words,” Pavlova says. “The Russian powers that be for a long time have had an ambitious plan for expanding their influence in one of the most ancient cities of the Middle East – Jerusalem – a plan which they are now carrying out.”

“It is no accident,” she says, that a Russian Spiritual Mission operates there and that “the Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society (IPPO) not long ago received official status in Israel” even though it traces its origins to tsarist times. During his visit to Israel last month, Stepashin outlined its current agenda.

“IPPO,” he said, “has structures both in Palestine and in Israel which already are carrying out on these territories unique ideological work. However, the Russian leadership considers as spheres of its influence not only [their] territories but also the present-day states of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and also Saudi Arabia.”

“A Russian school has been built in Bethlehem,” Stepashin continued. “The construction of schools in East Jerusalem is planned.” Russia has regained the territory in the city that Khrushchev gave up in 1964 just as it has regained Crimea. Russian influence is returning: “One of the streets of Bethlehem now bears Putin’s name,” Stepashin said.

But Moscow’s campaign to spread its influence is not limited to IPPO, Pavlova says. Instead, in order to oppose the US, Russia’s special services “intend to cooperate further with such organizations as Hamas and Hezbollah. And in order to expand Russian influence, it is taking a long-term view.

Moscow has just announced that its own economic problems notwithstanding, Russia has offered Egypt a 25 billion US dollar credit for the construction of its first atomic energy station, money likely to recycle back to Russia because Russian firms will be involved in this project.