The centrality of World War II in Vladimir Putin’s thinking has never been more evident than now when it is clear that he wants to restore a World War II-type alliance against ISIS, with all the ensuing consequences that would have for Russia, the international system, and those who fell under Moscow’s sphere of influence.

In a commentary for Spektr.press, Vadim Shtepa

suggests that Putin’s invocation of the World War II model for the fight against ISIS is “not simply a clever expression.” Instead, it reflect the Kremlin leader’s desire for “a literal remake of the historic events of 75 years ago.”

It will be recalled that in the 1930s, there took shape “three main subjects of the future war: the West (the US, the UK and France), the third Reich, and the USSR.” After handing over Czechoslovakia to Hitler, the West in September 1939 was forced to declare war on him,” Shtepa recounts.

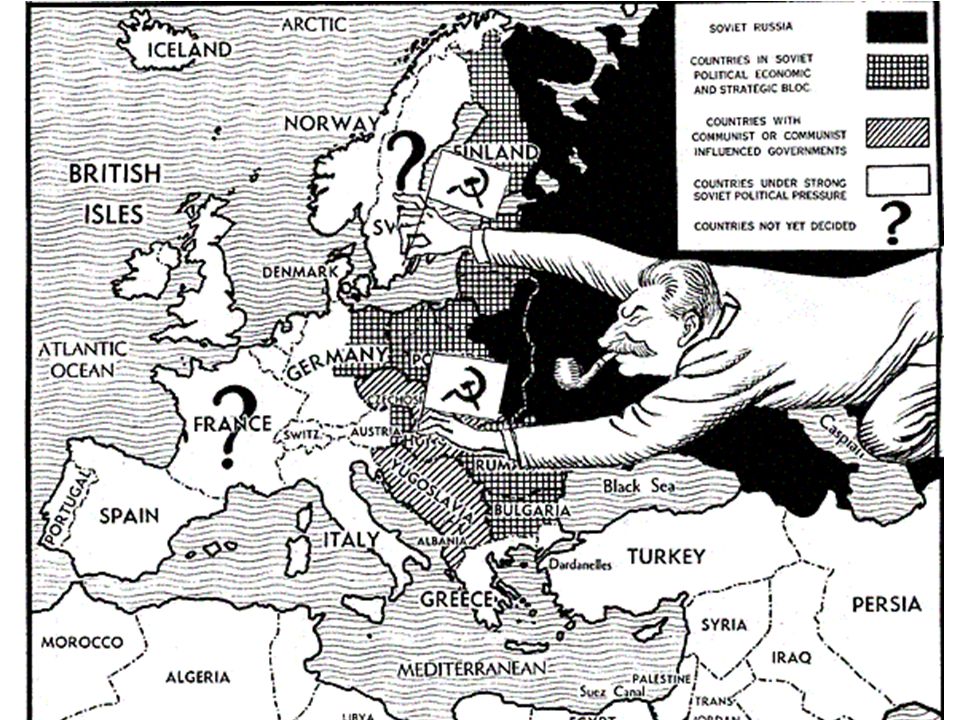

At the same time, “Stalin divided Eastern Europe with Hitler by concluding pacts of non-aggression and even friendship with him. But these pacts collapsed” with Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union, and there “arose the anti-Hitler coalition of the West with the USSR,” which had two consequences.

In the short term, it led to Hitler’s defeat; but in the longer term, it “led to the swallowing up of all of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union and the latter’s transformation into one of the two most important superpowers,” the Russian regionalist commentator writes.

“Today we are observing an effort to reproduce this situation which according to the intentions of its authors should be crowned with just as grandiose a global rise of ‘the legal successor of the USSR’” and, by making an alliance against ISIS, with the reversal of many of the results of the Cold War that the Kremlin doesn’t like.

That ISIS should be the focus also has parallels with the situation 75 years ago, Shtepa suggests. “On the one hand, this ‘neo-caliphate’ is prohibited in Russia and hostile to it. But [on the other,] in terms of many worldview values (hatred to Western ‘permissiveness,’ the stratification of ‘traditional religion’ and so on), it is surprisingly in tune with it.”

And that recalls the relations of Soviet bolshevism and German Nazism, which “despite their ideological opposition also completely corresponded in their totalitarian approaches and even models of propaganda.”

“Today,” Shtepa argues, “it has turned out that the Paris terrorist actions have played into the hands of official Moscow in its semi-isolation.” Moscow of course condemned the attacks, but “if one looks at the situation politically, these events open a new chance for Russia to escape from its status as an isolated ‘world outcast,’ that it has been in since the Crimean Anschluss.

And it is even the case, the Karelian writer continues, that there are parallels between the unrecognized "DNR" and "LNR" now and certain events at the beginning of World War II. Soviet aggression against Finland in November 1939 “was begun with the proclamation of ‘the Finnish Democratic Republic’” in the occupied city of Terijoki.

Moscow hoped to use that as a base to extend Soviet control throughout Finland just as Putin has hoped to use the "DNR" and "LNR" against Ukraine, but “the heroism of the small Finnish army destroyed” Moscow’s hopes. And “the League of Nations

excluded the USSR from its members.”

Comments by analysts close to the Kremlin like Sergey Markov and Aleksey Pushkov, Shtepa says, suggest that “these are not simply historical parallels but rather a direct succession of the technologies of imperial policy.” And those two spokesman recall Soviet propagandists of 1940-1941 in yet another way.

Between 1939 when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed and 1941 when Hitler invaded the USSR, Soviet propagandists denounced “Anglo-Saxon and French imperialists” on all occasions. But after the Nazi invasion, they quickly changed their tune and began to call them “’allies in the anti-Hitler coalition.’”

In 1941, “these allies were supposed to ‘forget’ the division of Poland by Stalin and Hitler, [Soviet] aggression against Finland, and the inclusion of the Baltic countries in the USSR.” Now, Kremlin propagandists are calling for the West “to ‘swallow’ Russian aggression against Ukraine and lift sanctions in the face of ISIS, a common and more dangerous enemy.”

Whether Putin will succeed in this remains to be seen, but one thing is already clear: Putin has clearly forgotten nothing from World War II and its aftermath; but some in the West have learned nothing from that time and from what its wartime alliance with Stalin brought onto those who fell under his “sphere of influence.”