There is a hoary Soviet anecdote about a group of very old Russian women marching through Red Square just after World War II. They are carrying signs saying “Thank you Stalin for Our Happy Childhood!” A secret policeman approaches and says “Grannies, you are so old that when you were children, Stalin was not yet born.”

To which the Russian women reply with dignity: “Why do you think we are grateful?” – the perfect combination of cleverness and contempt which distinguishes the very best Soviet political anecdotes and which makes them such a rich source of insights about the nature of that horrific system.

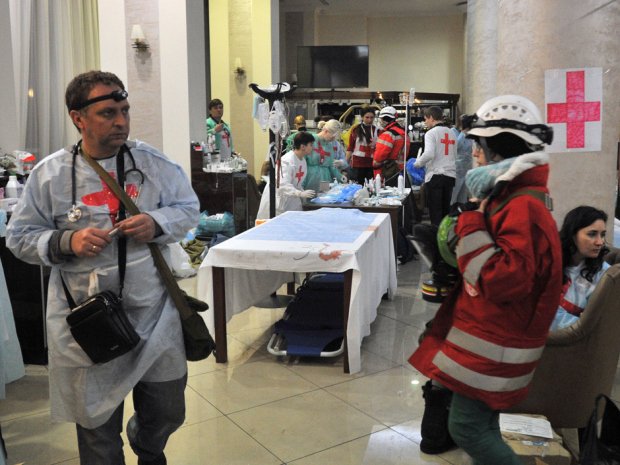

One is reminded of that fact when one reads a new commentary by Sergey Gayday, a Ukrainian political analyst and operative, on why “all Ukraine should be grateful” to Vladimir Putin, a man many of its citizens would be happy to see behind bars or even dead.

If he were writing Putin’s obituary, Gayday says, he would say many positive things about the Kremlin leader because “precisely he and his actions have brought [Ukraine] such enormous benefits.”

Ukrainians should be thankful to Putin because finally real patriotism has arisen in their country, not patriotism ordered from above but a common feeling that each individual has responsibilities for the whole. That provides “a good basis to build here in this country a worthy life, to defend it, and to struggle for it.”

They should also say “thank you” to Putin because “namely he by his actions did not allow us to keep in power the former criminally ineffective rulers” that we had voted for earlier but now, thanks to Putin, were prepared to send to the dustbin of history. And Ukrainians should be grateful that the Russian leader has made service in the army a matter of pride not shame.

“Until recently,” Gayday says, “the majority of Ukrainians considered that [they] didn’t need an army, that [they] had no enemies, and that there was no one to fight with.” Putin has cured them of that delusion. For that, they should be grateful too.

He suggests that Ukrainians should be grateful as well for the fact that Putin has put them on the way to becoming not just “the population living on the territory of Ukraine” but “a political nation,” a community of citizens who “think not only about their daily bread but about abstract things, in particular about how they ought to live.”

And Ukrainians should be grateful to Putin because he has led them to “choose Europe,” not in the form of membership in the European Union but in terms of European values, where “the chief thing is not the powers that be but the individual, where the former are only an element of service to all individual citizens taken together.”

Before Putin acted, “only 14 percent of [Ukrainians] thought [they] needed to join NATO; now, this figure has risen to 70 percent.” Again, thanks to the Kremlin leader more than anyone else.

And thanks to him also, Ukrainians “have finally concluded that the nostalgic ‘Soviet past’ must be expelled from each … Finally, [they must] study real history and not that invented in party offices. To begin to find out who in fact were the heroes of our people and who were its executioners.”

“For the last two years,” Gayday says, “no one of our government has done so much as this politician. If he had not existed, it would have been worthwhile to create him. In a word: ‘thank you, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin!’” And although the Kyiv analyst does not say so, this Ukrainian gratitude is something Russians should be reflecting upon as well.