Just as it did in Ukraine, Moscow is preparing again to play the citizenship card in Estonia and Latvia, muddying the waters as to who is “a Russian” and who is thus part of Vladimir Putin’s “Russian world” and worthy of Moscow’s defense whether any of them want that “defense” or not.

In the case of Ukraine, the Russian government at various points over the last six months has included in what Putin calls “the Russian world” “citizens of the Russian Federation,” “ethnic Russians regardless of citizenship,” “Russian speakers,” and those who identify with Russia regardless of their ethnicity, language, or citizenship.

Now as it steps up the pressure against the Baltic countries, Moscow is again using a highly elastic definition of who is part of the Russian world and who is not, something that must be understood and acknowledged if the Baltic countries and their supporters are going to be in a position to turn back Moscow’s efforts to subvert, destabilize and otherwise move against them.

An article by Nadezhda Yermolayeva in “Rossiiskaya gazeta” last week with the headline “Residents of Latvia are taking Russian citizenship in great numbers” provides both an indication of the direction the Russian government is moving and also the flexible way it is defining who is part of Putin’s "Russian world."

But even more valuable, although this was certainly not Yermolayeva’s intent, the article also provides important guidance on what the Baltic governments and their supporters in Europe may now face and should do lest the Kremlin leader succeed in so muddying the waters that many do not respond to his aggression until what may be too late.

According to Yermolayeva, “every 50th resident of Latvia is a citizen of Russia,” and their number is “growing from year to year.” And she says that specialists say that citizens of Latvia as well as non-citizens are now taking Russian citizenship, something that one of her contacts said “the Latvian authorities ought to be thinking about.”

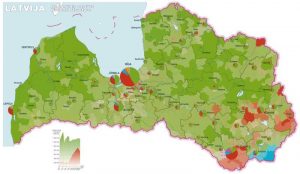

Some are doing so for purely economic reasons: the retirement age in Latvia rising and by changing citizenship some people can get pensions sooner. But more is involved than that, she suggests, noting that the number of people taking Russian citizenship now is especially large in Latgale, “the easternmost and poorest region” of the country.

According to the statistics Yermolayeva gives, 13 percent of the population of Latvia are not citizens of that country. That amounts to 288,000 people. In most cases, these are people who were moved into Latvia while it was occupied by the Soviet Union and thus could not qualify for citizenship under international law.

Many of these people are loyal to Latvia but resent the idea that they should have to apply for citizenship rather than gain it automatically, Yermolayeva says. But intriguingly she adds that such people are in some ways “the most privileged” group in the region because they have the right to travel freely in Europe and without a visa to Russia.

“In neighboring Estonia,” the Moscow journalist continues, “the number of ‘non-citizens’ is lower than in Latvia” – only seven percent of the population is in that category. But at the same time, the number of Russian citizens is higher” – seven percent according to the Baltic Institute for Social Science.

The reason for this difference in the balance of persons without citizenship and those with Russian citizenship, the Moscow journalist continues, is a product of different decisions of the two countries in the 1990s. But it has important consequences: in Estonia, there are no “powerful and independent Russian-language political parties,” but in Latvia, there are.