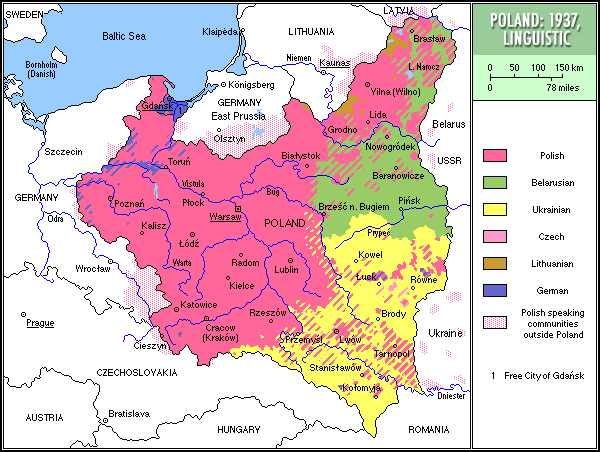

Galicia and Volhynia have, over their history, long been subject to changes of power. In the twentieth century and with the outbreak of both World Wars, this fact could not revisit itself more often. The region, home to both Poles and Ukrainians, became locked in war between the two groups as they struggled for post-war sovereignty against a sprawling Germany and Soviet Union. While these two groups have not always been on amiable terms (primarily due to the centuries-long struggle for Ukrainian independence), World War II brought any and all tensions to the forefront, and it is under these multiple occupations that a devastating civil war and series of ethnic cleansings were made possible. Known as the Volhynian slaughter in Polish and Volhynian tragedy in Ukrainian, the Polish-Ukrainian conflict in Galicia-Volhynia was a tense and pitiless struggle between Poles of the Home Army (AK), partisans, and self-defense formations and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalist’s (OUN) Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). Some scholars ascribing to certain national narratives, however, fail to realize the scale and reciprocal nature of the conflict from beginning to end, even though both sides struggled for identical goals through identical means. This period was not limited to a single campaign of ethnic cleansing, but rather an ongoing chain reaction of cleansings that began and culminated under the auspices of multiple occupational regimes actively seeking to provoke and maintain this state of chaos. By looking at the events that took place as part of an extended continuum with multiple actors, and not as an isolated or one-sided event that spanned only a handful of years, we can better understand both the causation that led to and perpetuated this conflict, as well as the true gravity of events that unfolded for both sides.

Thrice Occupied

The ethnic cleansing that occurred between Poles and their Ukrainian neighbors cannot be simplified or viewed as an isolated, sporadic, or one-sided event that occurred without precedent, evocation, or meaning. Even within the contemporary framework of it occurring as a byproduct of their mutual civil war, to fully understand the causal relationship that set these events in motion, one must place this civil conflict within the context of the World War that it paralleled. The instability of Galicia-Volhynia and the bordering region in general, can most easily be explained by its geographical misfortune of enduring a “triple occupation” that occurred in four successive waves.

Polish occupation fostered the growth of later insurgency

The first of these occupational waves took place in the aftermath of the First World War. The attempted creation of nation-states in Poland and Ukraine carried with them the same transitional issues similarly situated European states endured. In this transition away from an agrarian to a modern polity, cross-border friction over land ownership was only made worse by the authoritative policies of the Polish state at the time. With the newly reformed Polish state no longer imperial in design, ethnic cleavages were especially pronounced in the voivodships within Galicia and Volhynia where the Polish elite continued to rule as a minority of the population. On a local level, first hand reports cite the killing of Ukrainians along the San River. On an official level, Poles ruled heavy-handedly from 1920-39. In defiance of the League of Nations and its attempt to demarcate a border between two ethnic groups (known as the Curzon Line) Poland occupied and proceeded to divide Ukrainian lands with the Soviet Union. Ukrainians considered Polish occupation to be thrust upon them, whereas Poles considered western Ukrainian lands to be a necessary possession for state security. British commentary on government policy exclaimed that persecution provided Ukrainians with an “added consciousness and solidarity” and that Polish severity actually “increased the insecurity of the south-eastern frontier of the republic.” The Polish narrative tends to ignore the behavior and consequences of its interwar government. It should have come as no surprise, though, that the repressive policies of Jozef Pilsudski and the Polish colonization of Ukrainian territory fostered the growth of later Ukrainian insurgency.

Soviet occupation spawned even more hatred among the Ukrainian population, radicalizing it.

The second wave of occupation occurred in 1939 following the Soviet invasion of Poland. Already a region conducive to violent inter-ethnic conflict, the San now acted as the boundary between the zones established by the Soviets and Nazi Germany. Following the division of Poland, “everything changed.” Massive, state-organized political and ethnic violence carried out by both parties introduced a divided Poland to its first exposure of massive ethnic cleansing. From 1939 to 1941, “an unprecedented terror swept the recently conquered areas of Western Ukraine.” For Poles, tens of thousands were killed and hundreds of thousands were deported by both occupational regimes – Ukrainians also suffered immensely. Soviet occupation is said to have “decapitated” Polish and Ukrainian society, in which Galicia especially was completely torn apart. The mass devastation notwithstanding, Soviet occupation spawned even more hatred among the Ukrainian population, radicalizing it.

Nazi occupation had a clear cause and effect, with massacres beginning as early as 1941

The third wave, that in which Nazi Germany occupied Galicia and Volhynia, was the most decisive in converting these pent up frustrations into fully realized ethnic cleansing. While inter-ethnic violence between Poles and Ukrainians had been longstanding, Nazi occupation had a clear cause and effect, with massacres beginning as early as 1941. Under this new occupation the San River no longer acted as an important boundary. Instead, Volhynia was placed under the administration of the Nazi German colony called the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, and Galicia within the Generalgouvernment

, which was part of Greater Germany itself. New social and political divisions were established in a short period: in Galicia, Ukrainians were elevated to positions of authority whereas in Volhynia, Poles retained authority within the German administration. Volhynia faced a harsher occupation in general, and due to its northern location, quickly became a battleground for Soviet partisans. Volhynian society was reduced to chaos by 1943.

Panic & Desperation

Hitler’s genocidal policy to exterminate Europe's Jewish population, the Final Solution, began in 1942, but prior to this the population was already well exposed to an immense population displacement enforced by the Germans. Meanwhile, from Soviet Ukraine, propaganda promoted the possibility of a free and united “great Ukrainian people,” one that included Galicia and its crown jewel, Lviv. On the whole, the precedent for ethnic cleansing and the popularity of fascist and Bolshevik nationalism made perfect ingredients for what remained of a devastated society to reciprocate the words and actions of the newly imposed authority.

The prelude to full scale ethnic cleansing by Ukrainian insurgents ends in 1943. Ukrainian leaders believed the war would end with attrition warfare exhausting both Germany and the Soviet Union. Out of this, a resurgent Poland would be the primary obstacle in the way of Ukrainian statehood. The Soviet counteroffensive that followed the battle of Stalingrad in January of 1943 led to a westward push by Soviet forces as they recaptured Ukraine proper, leading Ukrainian leaders to reason that a preemptive elimination of Poles from Ukraine would be the most they could aspire for in a relatively short period. In the words of Roman Shukhevych on 25 February 1944, due to the success of the Soviet forces it was "necessary to speed up the liquidation of the Poles," "they must be totally wiped out."

As the Soviet and German armies waged war on one another for control of Eastern Europe, the Polish-Ukrainian civil war continued to be fought for sovereignty over land that neither side still controlled. Nonetheless, claims were made whose terms were unnegotiable: politically active Poles wanted to restore the 1939 borders whereas Ukrainians called for primacy over their own ethnic territory. Ukrainian concerns of Polish intentions were not unfounded, and with the question of legitimate rule over Galicia-Volhynia reopened, political proposals had already been made to deport up to 500,000 Ukrainians from an imagined ‘post-war Poland with pre-war frontiers’. Dmowski’s National Democrats went as far as desiring the entire expulsion of Ukrainians from the Polish state. Talks that did take place were fruitless, as was the case in Lviv of 1942 between the OUN and Polish government-in-exile, the latter of which insisted Volhynia was a “mixed territory.” While some historians contest the legitimacy of Polish claims to these lands, Poles had indeed lived on these lands for centuries; Volhynia alone had a pre-war presence of 400,000.

The rejection of Polish land rights was not a view held among the radicalized; even moderate Ukrainians failed to see any legitimacy in Poland’s aspirations. However, the radical among the OUN were passionately determined to prevent the clock from being rolled back and instead wanted to revisit attempts to begin a Ukrainian nation-state. This was a difficult proposal, though, because the creation of states is harder to accomplish than the restoration of states. To expedite the process and acquire legitimacy among its population, ethnic cleansing was seen in this instance as a distinct political answer.

Debated Origins

In determining where, when, and how the conflict began and who threw the first stone, Polish and Ukrainian views differ greatly. Some Ukrainians are of the opinion that the conflict began with the killing of Ukrainian underground soldiers and activists by the Polish underground, who considered them German collaborators. Others reject this notion and claim that the killings began as an OUN initiative, unrelated to the prior actions of the Home Army. Another claim is that the Ukrainians of Volhynia turned on the Poles after Polish Soviet partisans arrived in region, singling out the Ukrainian population.

German and Soviet authorities actively pursued a policy of provocation to pit the two sides, Polish and Ukrainian, against each other in order to divide and conquer.

Regardless of which side shot the first bullet in the sequence of events culminating in the ethnic cleansing of 1943, neither side acted independently. Just as social tensions were brought to a boil by the multiple occupations the region endured, the German and Soviet authorities actively pursued a policy of provocation to pit the two sides, Polish and Ukrainian, against each other in order to divide and conquer. It is this factor which explains the issue of competing historical narratives of victimization from each side. [highlight]Beginning in 1939, Soviet agents provoked conflict between Poles and Ukrainians in order to bring about “revolution” and justify the extension of the Ukrainian SSR into Polish territory beyond the San. In order to colonize the region and expand their Lebensraum (living space), Germans utilized preexisting tensions to let the colonized kill themselves off. In an example of “German meddling,” Germans offered Ukrainians a chance to persecute Poles in 1941-1942, and then, following Ukrainian desertions en masse to join the UPA, conscripted Poles to persecute Ukrainians the following two years.[/highlight] Another tactic used by Germans was to deploy, for example, forces against the Ukrainian population dressed as Polish soldiers, and vice versa. These provocative measures succeeded, so that each side remains steadfast in its conviction regarding victimhood and the actions of the historical “other." These provocations proved to be extremely successful, but how did they result in such widespread violence between both societies? The simple answer is that the attrition of war wore down both sides to such an extent that ethnic cleansing could not be prevented. A complete breakdown of governance and justice essentially decapitated civil and local society, leaving both sides to rely on their respective underground military organizations as the only source of authority. The Ukrainian organization in particular by 1943 was left only with its youngest and most radical supporters.

Ukrainian Bloodshed

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army’s program of ethnic cleansing began in earnest in March 1943, but sporadic killings had already started through the fall of 1942; the earliest accounts being in the Sarny region of Volyn and continuing throughout the winter. Since Ukrainian police held a more significant role in Volhynia than Galicia, this made for an explosive situation when in March 1943, Ukrainians abandoned their roles in the German police, taking with them their weapons and firsthand experience in implementing German atrocities. The UPA’s forces in Volhynia would reach as many as 20,000 troops; however, approximately ninety percent of the UPA’s attacks would collectively take place in the Galician provinces of Stanislaviv, Drohobych, Ternopil, and Lviv. The majority of the UPA’s attacks in Volhynia aimed at cleansing the region occurred throughout March-April, July-August, then in tailed off by late December of that year. Many victims included innocent Polish civilians, but some analysis has shown that main targets still included AK and partisan formations, indicating that the UPA’s presence was not limited to punitive actions against ethnic Poles but also retained its military purpose in this war. The goal of the OUN was not to exterminate each and every Pole, but rather to swiftly and brutally enforce the resettlement of all Poles to the west of the Curzon Line, preventing any future possibility of claims toward the territory being “mixed." In addition to Poles, factionalism within the OUN caused Ukrainian insurgents to kill tens of thousands of Ukrainians for siding with either the Melnyk or Borovets factions. Ukrainians who converted to Roman Catholicism were also killed.

By January 1944 the war had spread to Galicia but demographic conditions favoring Poles likely caused a reduction in the violence. Polish families, unlike in Volhynia, were presented a warning with the option of flight. Notices left on doors of Polish residences in Galicia stated the rationale behind their actions: “Because the Polish government and Polish people collaborate with the Bolsheviks and are bent on destroying the Ukrainian people on their own land, [name] is hereby called upon to move to native Polish soil…” Ethnic cleansing by the UPA was highly political in nature, and in addition to Poles and Melnykite Ukrainians, the course of the war tallied an estimate of 22 thousand pro-Soviet Ukrainian civilian losses at the hands of the UPA. By the spring of 1945, the UPA and AK had come to a truce, but conflict between Ukrainians and Soviet and pro-Communist Polish forces continued.

...and Polish Bloodshed

Even prior to the “official” outbreak of ethnic cleansing by Ukrainians, massacres aimed at the Ukrainian population of Kholm had started as early as 1942.

Historians in the Ukrainian diaspora focus on the Polish “retaliatory” actions that occurred during this conflict, and rightly so. Much like the preemptive nature of the Ukrainian attacks in Volhynia, as early as 1941 Poles equated war with Germany to war with Ukrainians for Galicia-Volhynia, and sought to achieve a quick “armed occupation.” In order to carry out retaliatory actions against Ukrainian aggressors, Polish partisans created self-defense formations. Retaliation, however, was carried out inch for inch, and was ‘hardly less fierce’. Warnings to Ukrainians made in 1943 stated that every village burned would result in two Ukrainian villages being razed, and for every Pole killed, two Ukrainians would be killed in his place immediately. Orders issued in February of 1944 by Polish Home Army commander Lt. Kazimierz Babinski said only children would be spared; however, a month later a massacre by Polish partisans occurred in Kholm killing 1,500, of which 70% were women and children. The largest groups (namely the Wiklina, Kozaka, Korczaka detachments of the Polish Home Army) played a considerable role, cleansing the Ukrainian population from Kowal, Wlodzimierz, and Lubomel in 1943-44. By the middle of 1944 the feeling of many Poles was that they would still retake or even extend territory into Ukraine. That summer approximately 150 villages, home to 15,000 Ukrainians, had been razed in so-called retaliatory measures. Attacks aimed at eliminating civilian populations were not uncommon from the Polish side. Even prior to the “official” outbreak of ethnic cleansing by Ukrainians, massacres aimed at the Ukrainian population of Kholm had started as early as 1942. Often, even when no direct orders from the Polish government-in-exile were given, this had no bearing on impeding retaliatory measures, causing Ukrainians civilians in many cases to be killed indiscriminately and on sight. Retaliation also took place by proxy, whereby upon hearing new of killings in Volhynia, for instance, Poles in Galicia would take up arms against local Ukrainians.

Following the German retreat, Poles ethnically cleansed their environs to an even greater degree, spreading from neighboring villages to isolated settlements. By late 1945 and into 1946, the modus operandi of the Polish Army was to attack UPA units in order to justify attacking Ukrainian settlements, wait for Ukrainian retaliation, and use that as further justification for “retaliation." These methods were cyclical, and clearly illustrate the reciprocal nature of this conflict. A multidimensional conflict, Polish retaliation and instigation took several forms: fighting Ukrainians as German policemen, NKVD battalions, Soviet partisans, and as self-defense militias and members of the Home Army.

From 1944-47, during the final occupational wave in the region, Soviet forces in collaboration with local Polish communists enacted a broad and final act of ethnic cleansing to end the conflict once and for all. Much like the original goals proposed by Polish and Ukrainian leaders, Soviet-mandated ethnic cleansing was used as a means to an end with violence utilized to solidify and legitimize state control. Polish veteran officers who had served as partisans during the Second World War were unsympathetic, and like the UPA in 1943, they knew that the war would only be won by "drastic measures." Ultimately, both Ukrainians and Poles were purged of their land on a staggering scale. In order to solve this “Ukrainian problem,” a series of deportations and forced relocations, named Operation Vistula

, acted as a direct successor of, and brought an end to, the ‘ethnic redefinition’ of Poland and Ukraine as states virtually homogenous in their ethnic composition. The goal of each side was finally, painstakingly, actualized.

The Toll

Both sides were positioned, motivated, and subsequently suffered in a relatively equal manner during the events that took place in Galicia-Volhynia. What may have begun as a series of sporadic clashes was provoked and focused into an exhaustive ethnic cleansing campaign that not only brought upon itself retaliation, but reciprocation. The Ukrainian campaign was especially brutal in its earliest months but as time wore on the Polish response made for substantial losses on both sides. Presented to be a force that acted in retaliation, in reality, the Polish forces are equally as guilty as the Ukrainian for aggression in the battle to stake the post-war claim to Galicia and Volhynia. Taking place in the heart of the eastern front, the actions of both Nazi and Soviet genocide and ethnic cleansing transferred to the local levels, and continued well beyond the end of the war. What began as two states trying to carve out their very own legitimate nation states in the face of losing what they once had, in the end resulted in neither attaining their wish.

Article by Mat Babiak & co-published on Ukrainian Policy